INDUSTRIAL

&

TERMINAL RAILROADS &

RAIL-MARINE OPERATIONS

OF BROOKLYN, QUEENS,

STATEN

ISLAND, BRONX &

MANHATTAN:

High

Line West Side Line West Side Improvement Project Meatpacking District National Biscuit

Nabisco Uneeda cold

storage Merchants Refrigerating Manhattan Refrigerating Hells Kitchen Chelsea Village Tribeca upper horse escort

manhattan cowboy Death Avenue Eleventh Avenue 11th Avenue Tenth Avenue 10th Avenue

Washington

Street

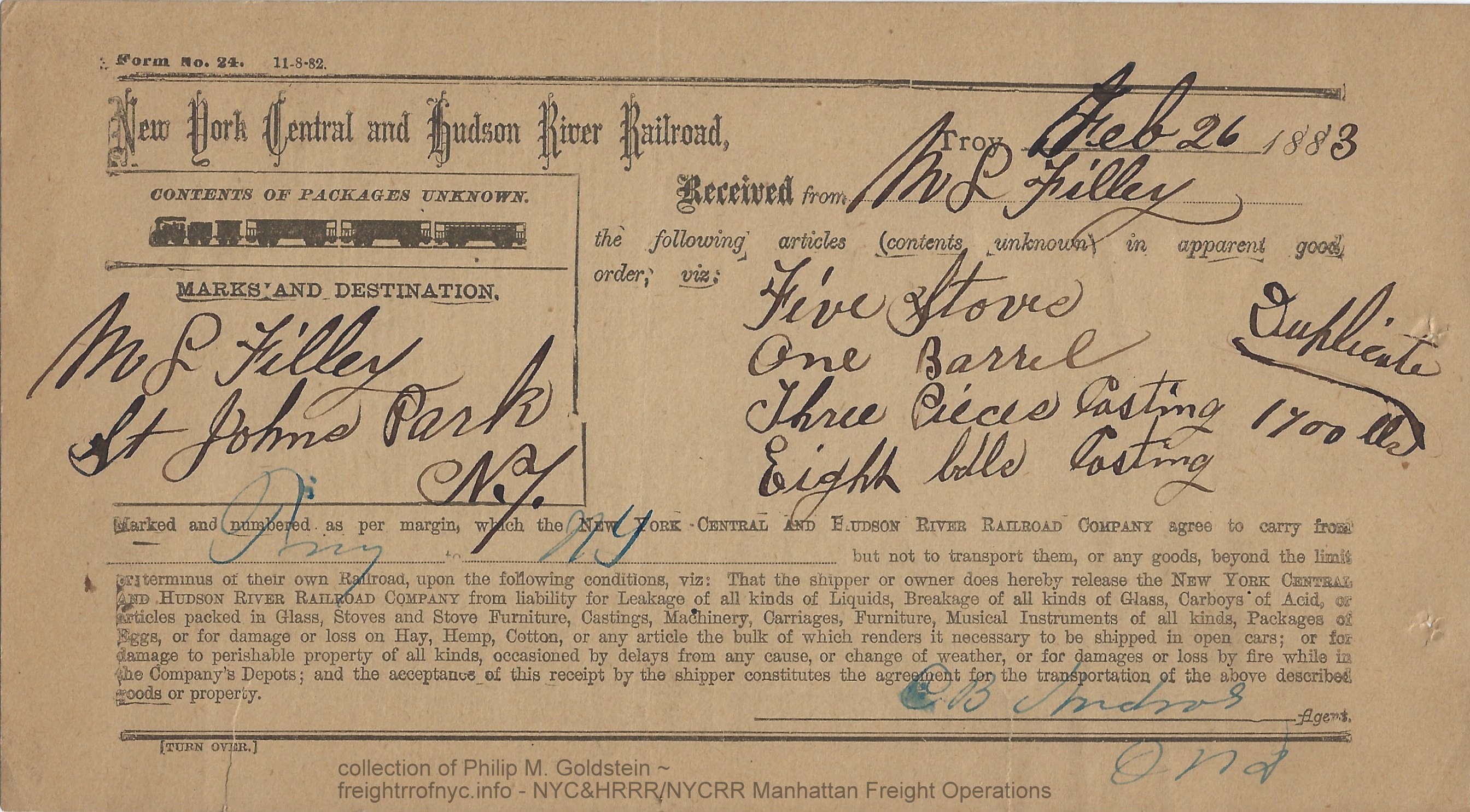

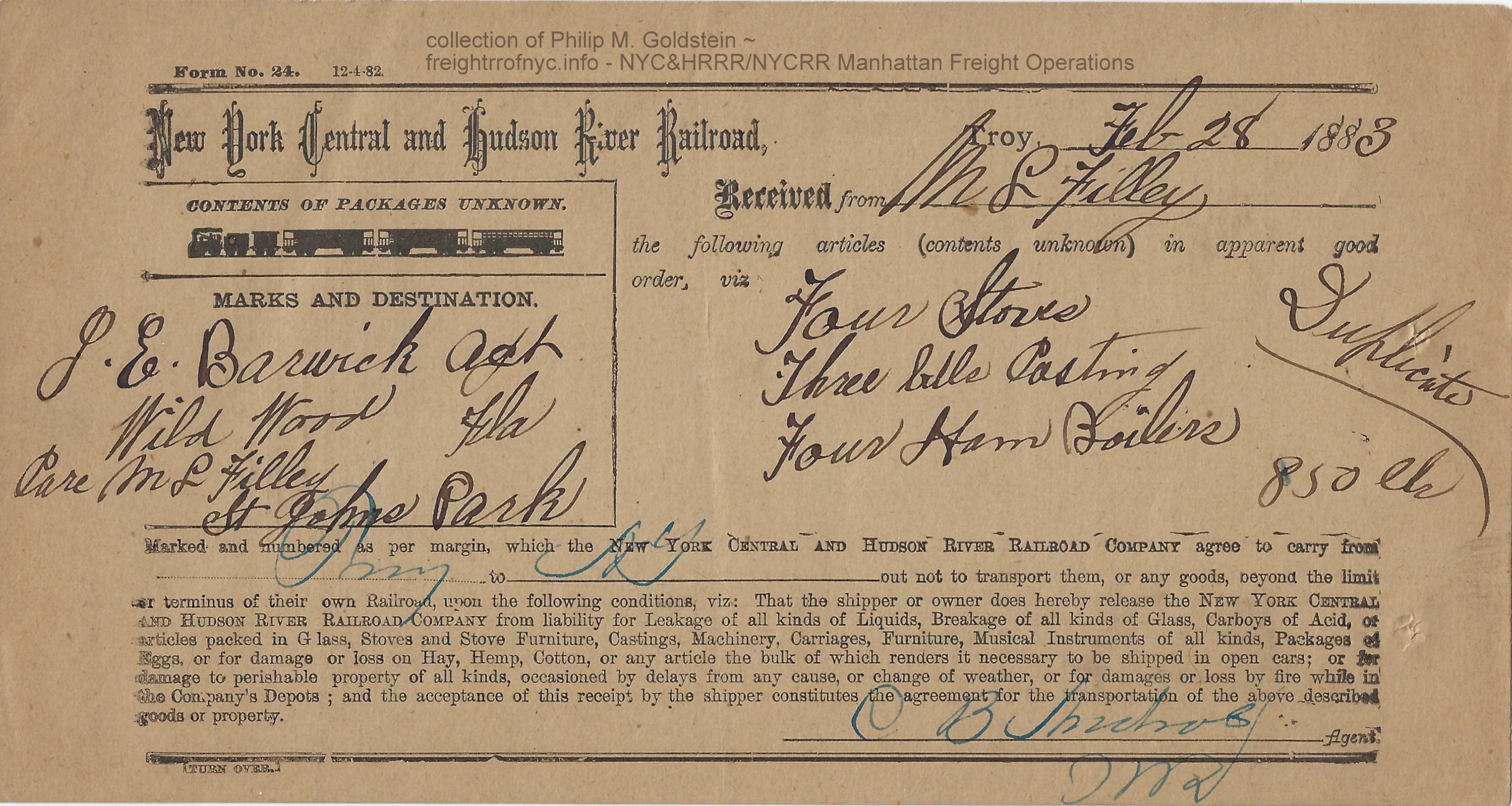

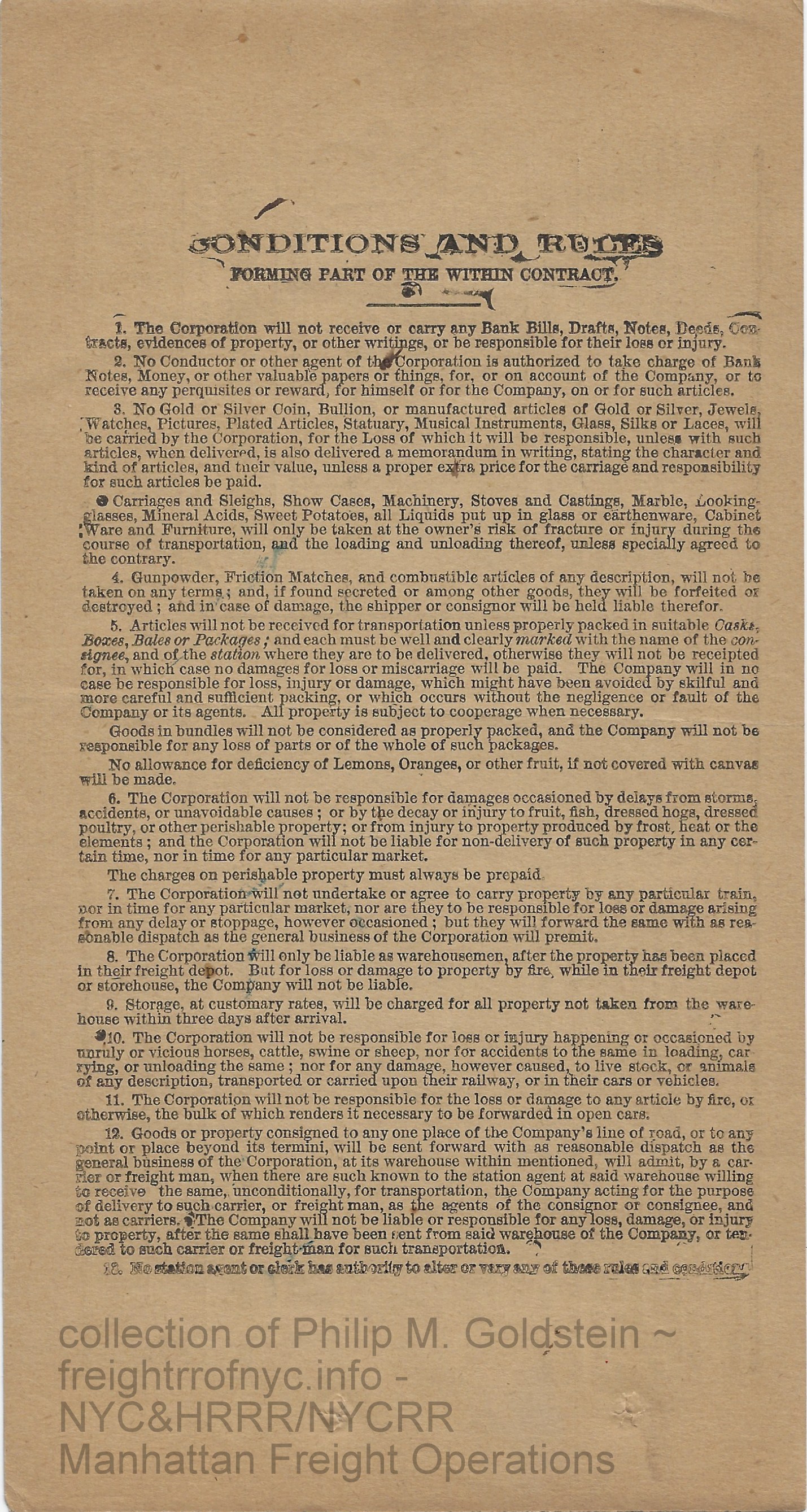

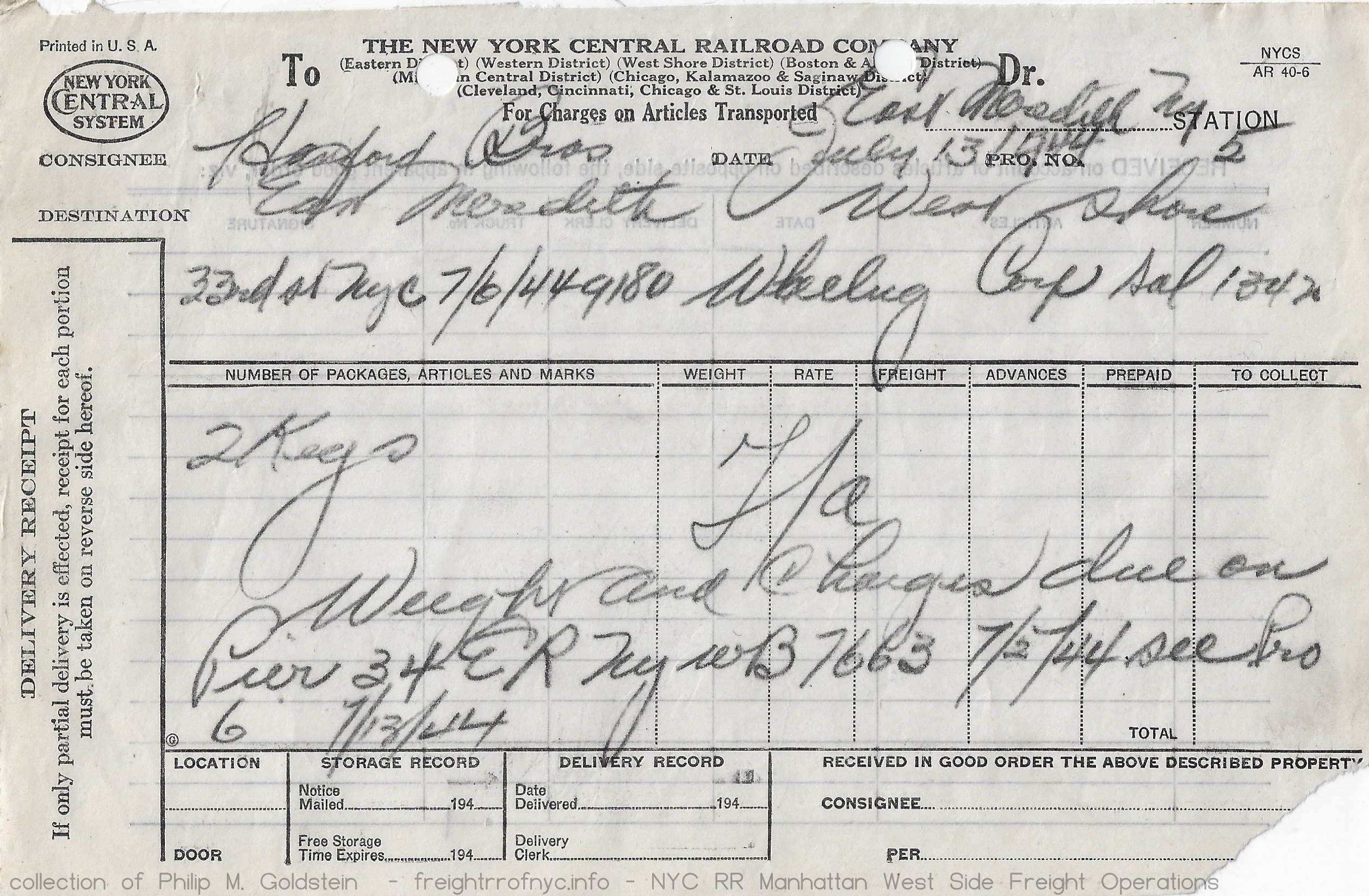

St. John's Park Freight Terminal street running trackage steam dummy

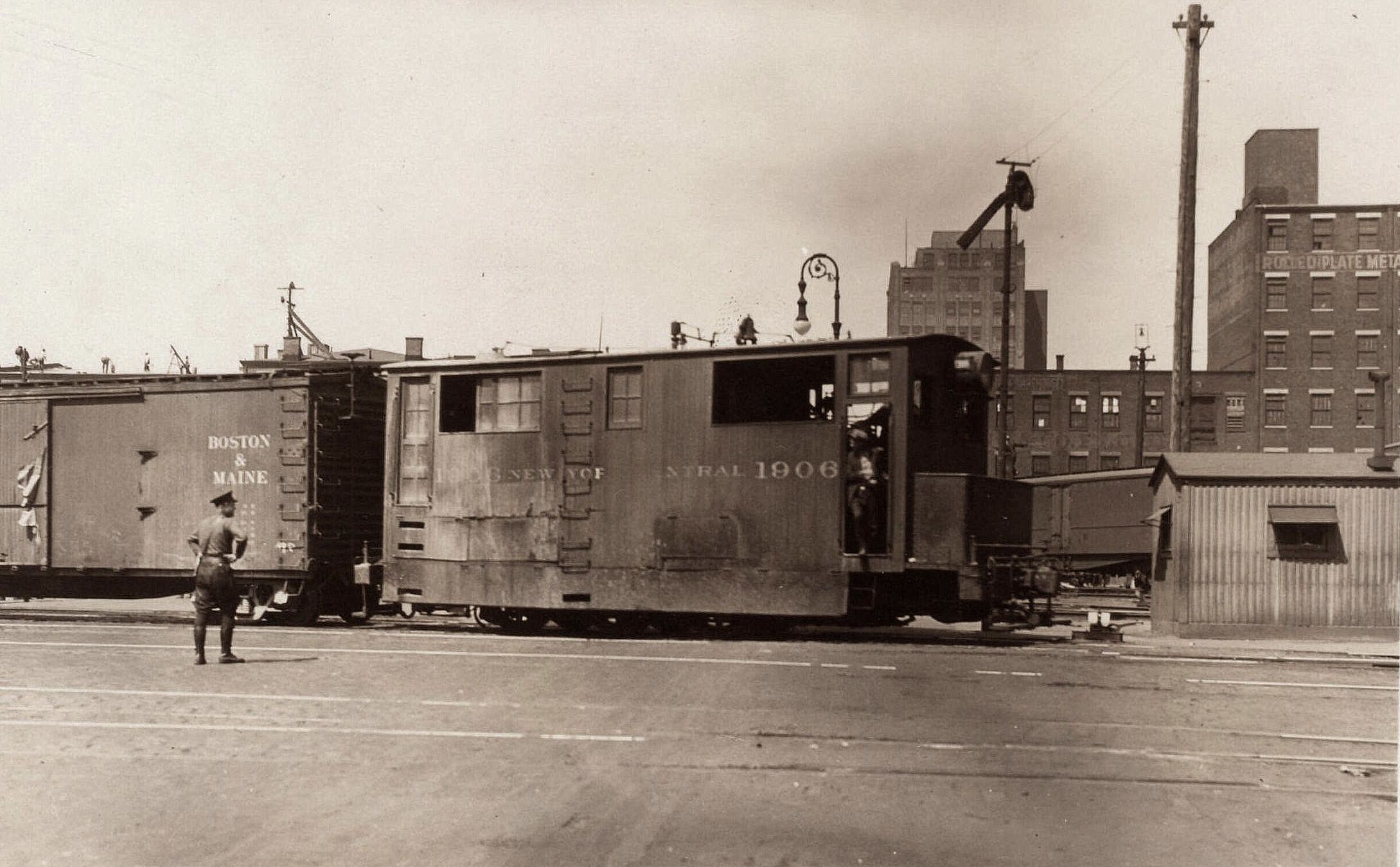

Baldwin American Locomotive ALCO Schenectady 0-4-0 0-6-0 B-B tripower

tri-power Lima Shay

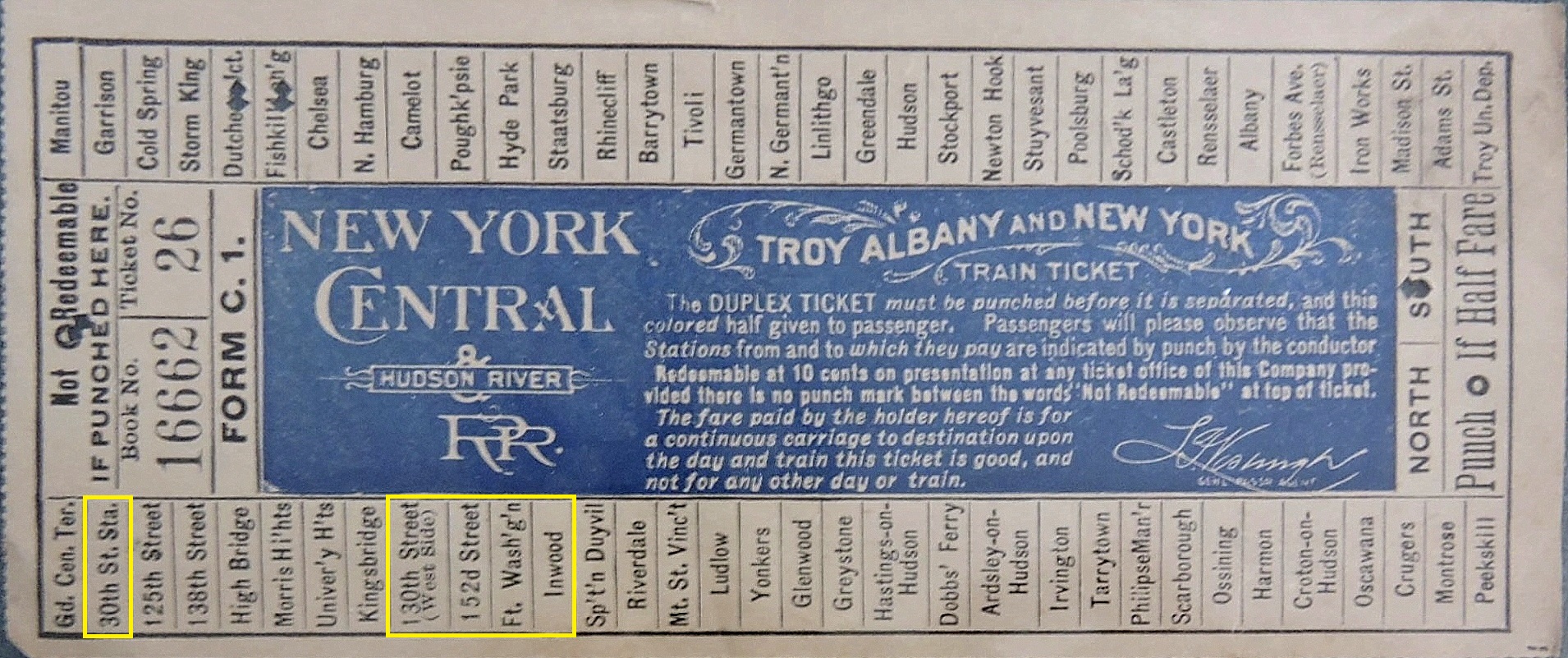

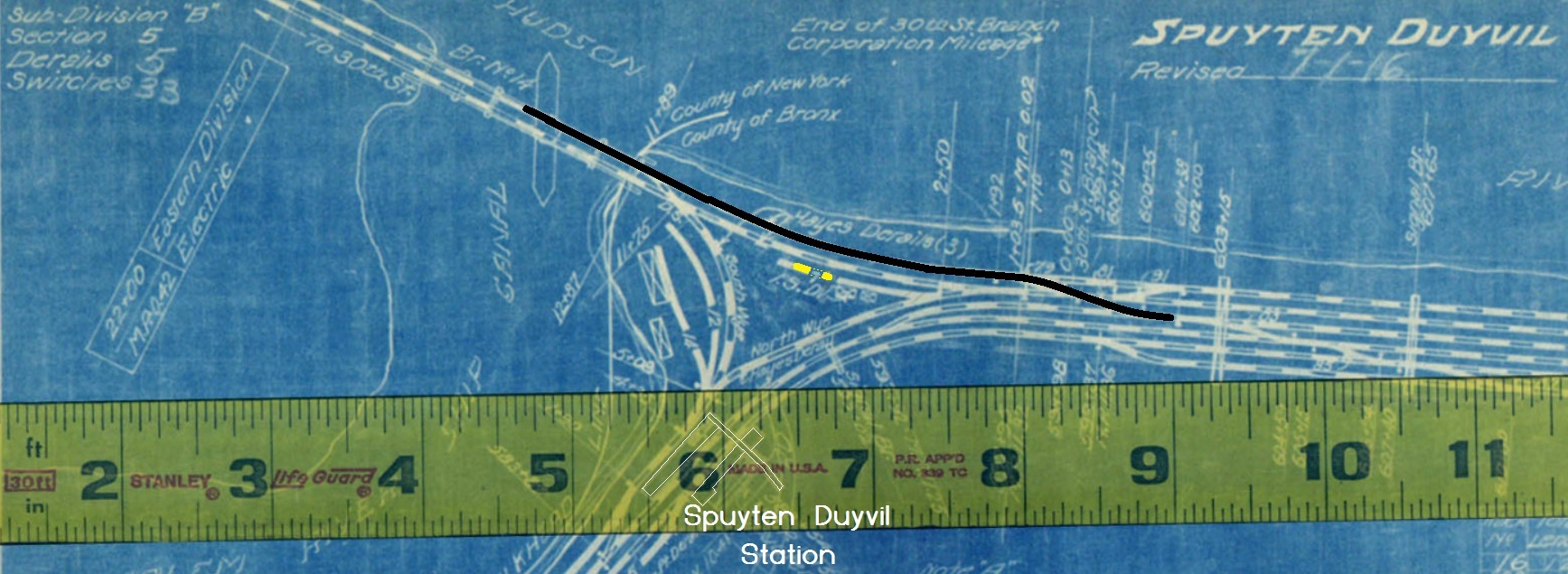

geared 30th Street Branch

.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

.

|

updated: |

||

|

|

||

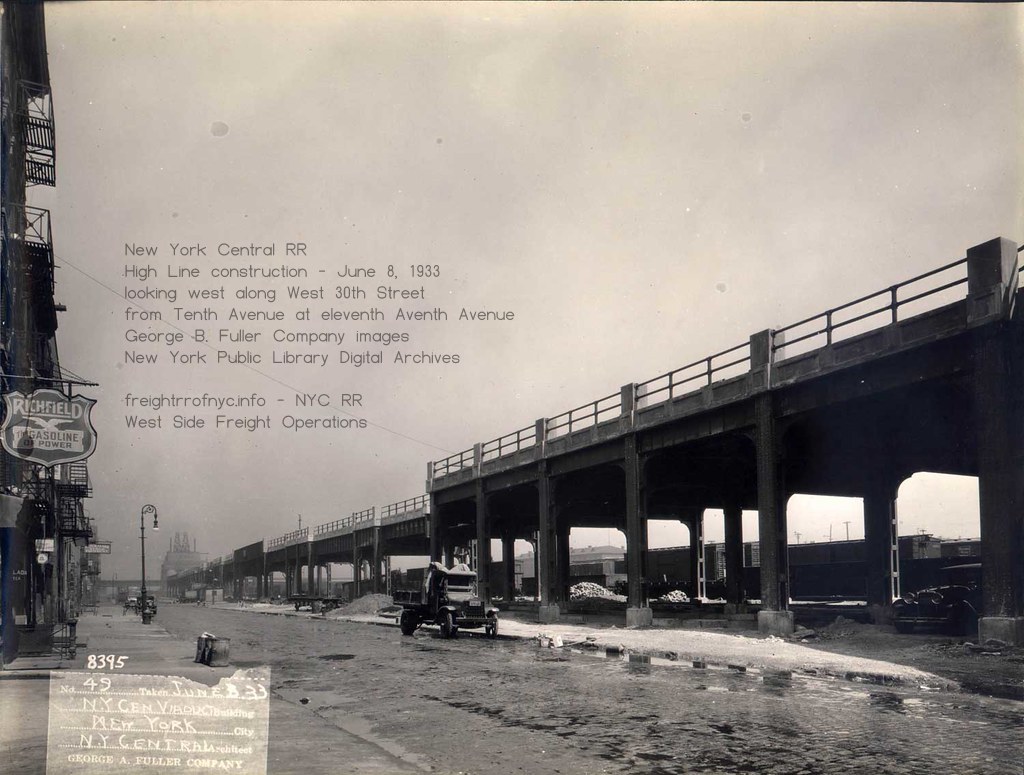

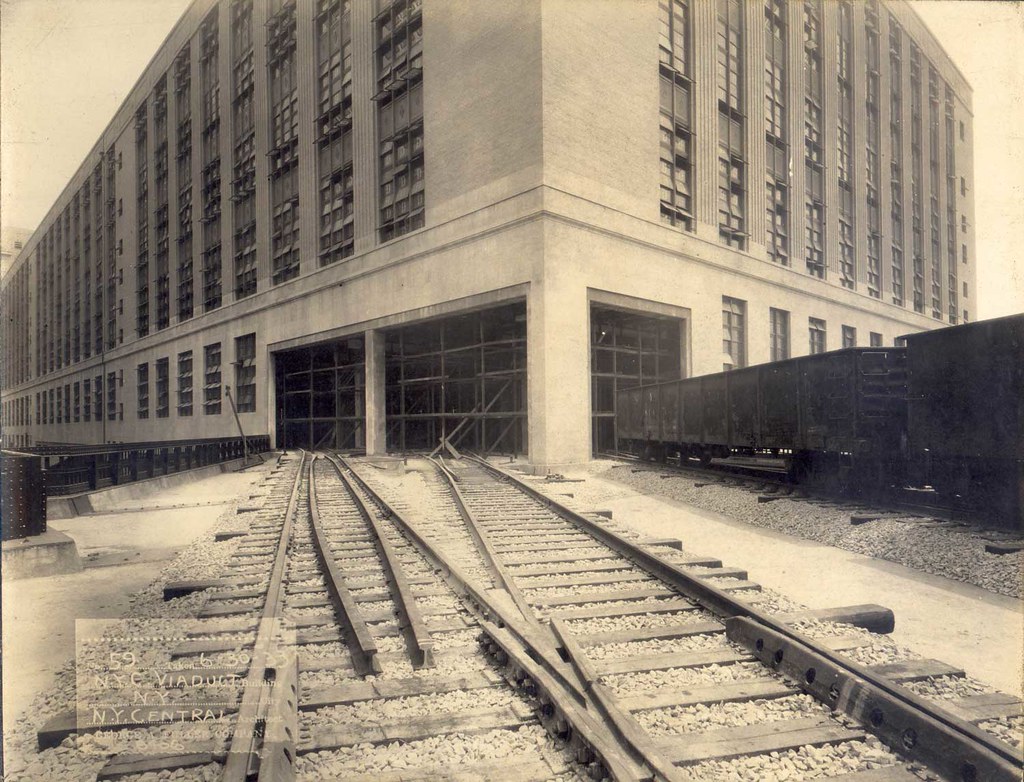

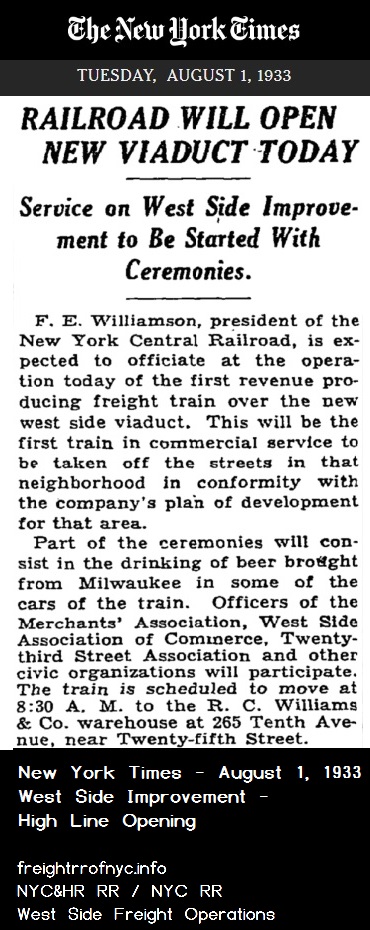

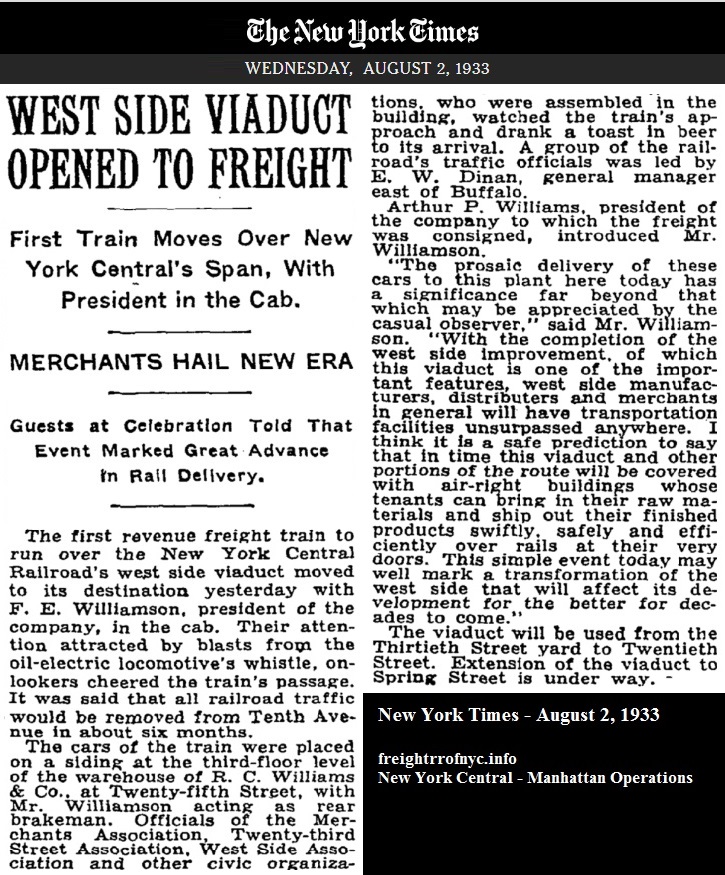

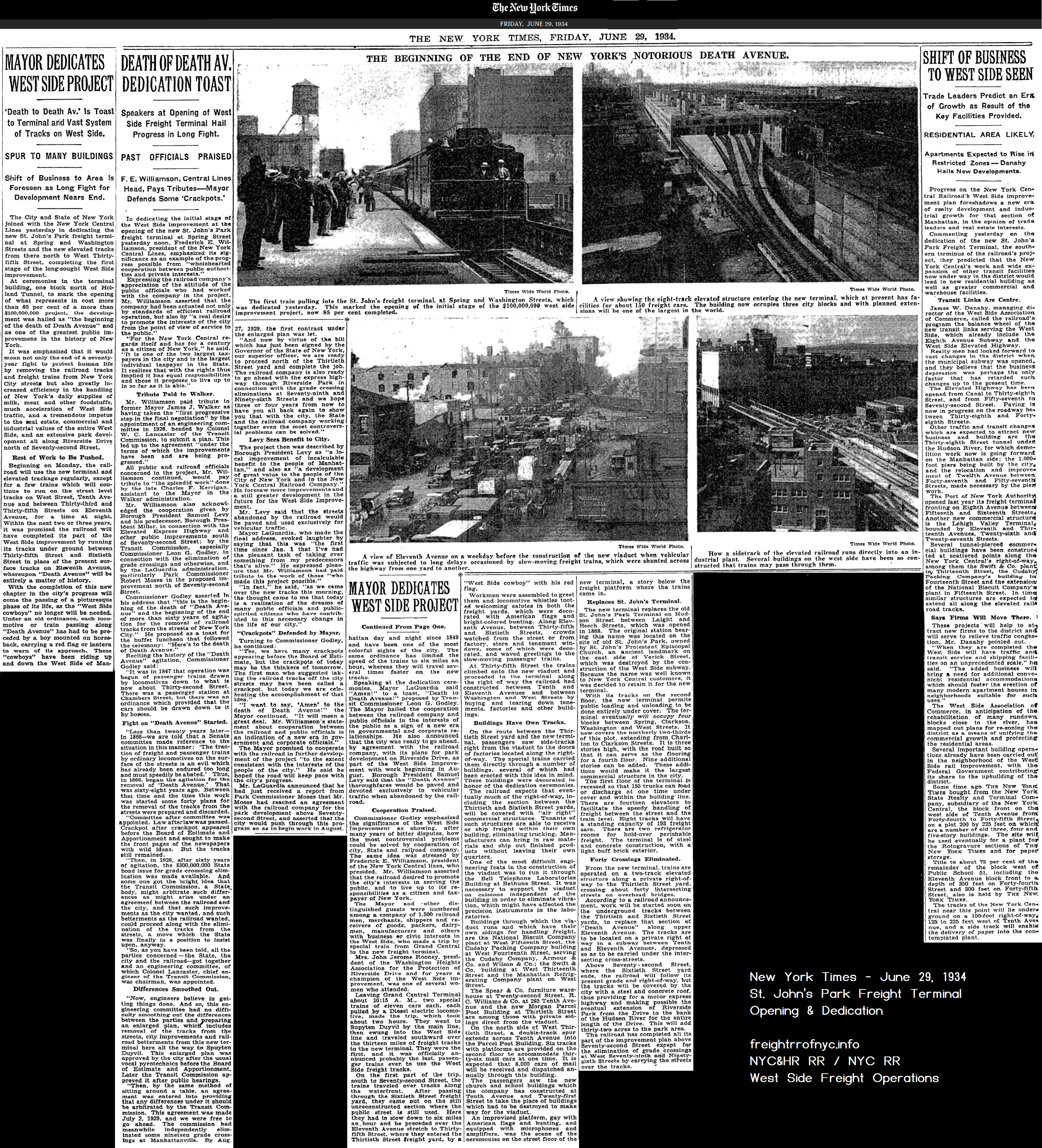

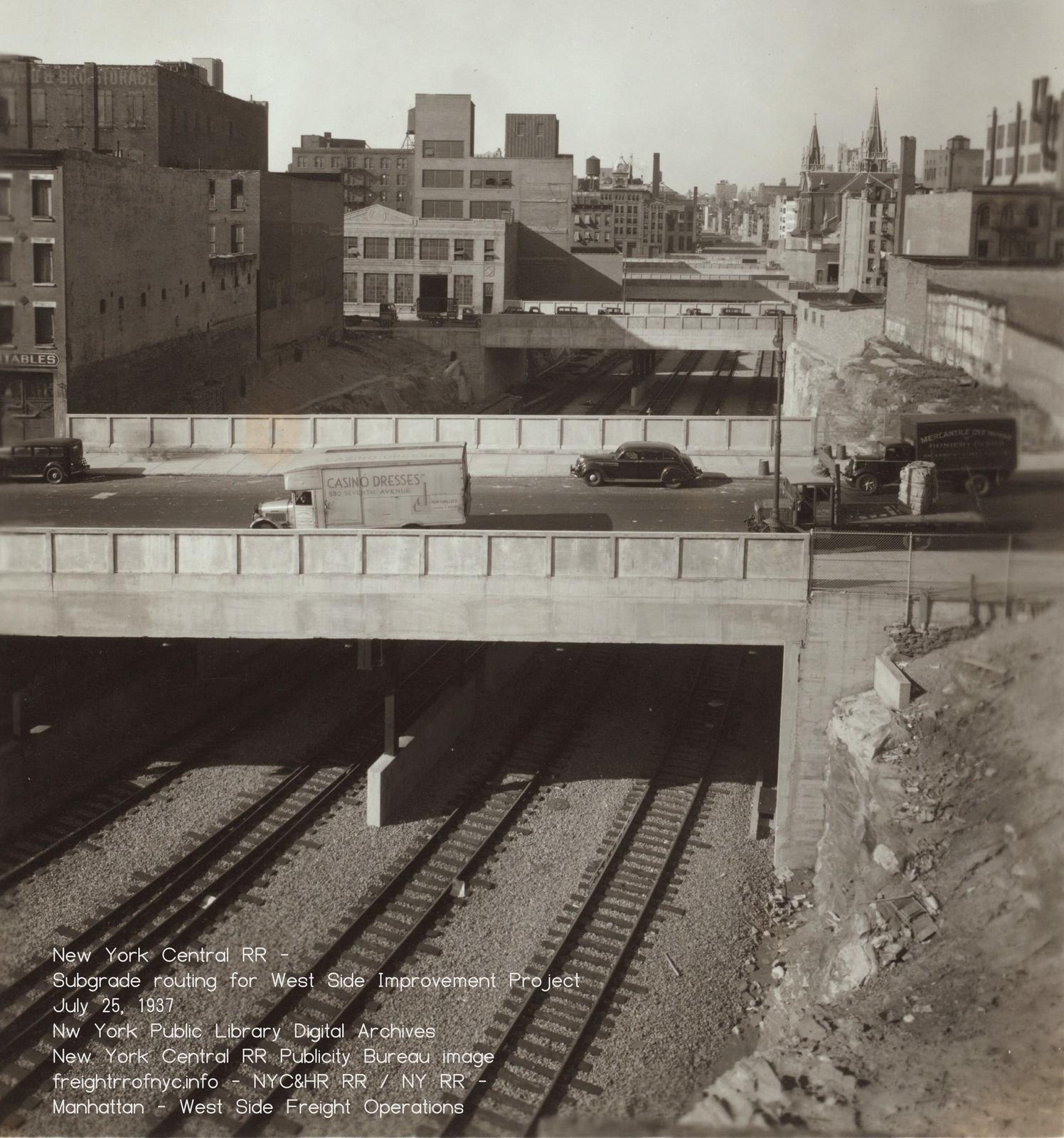

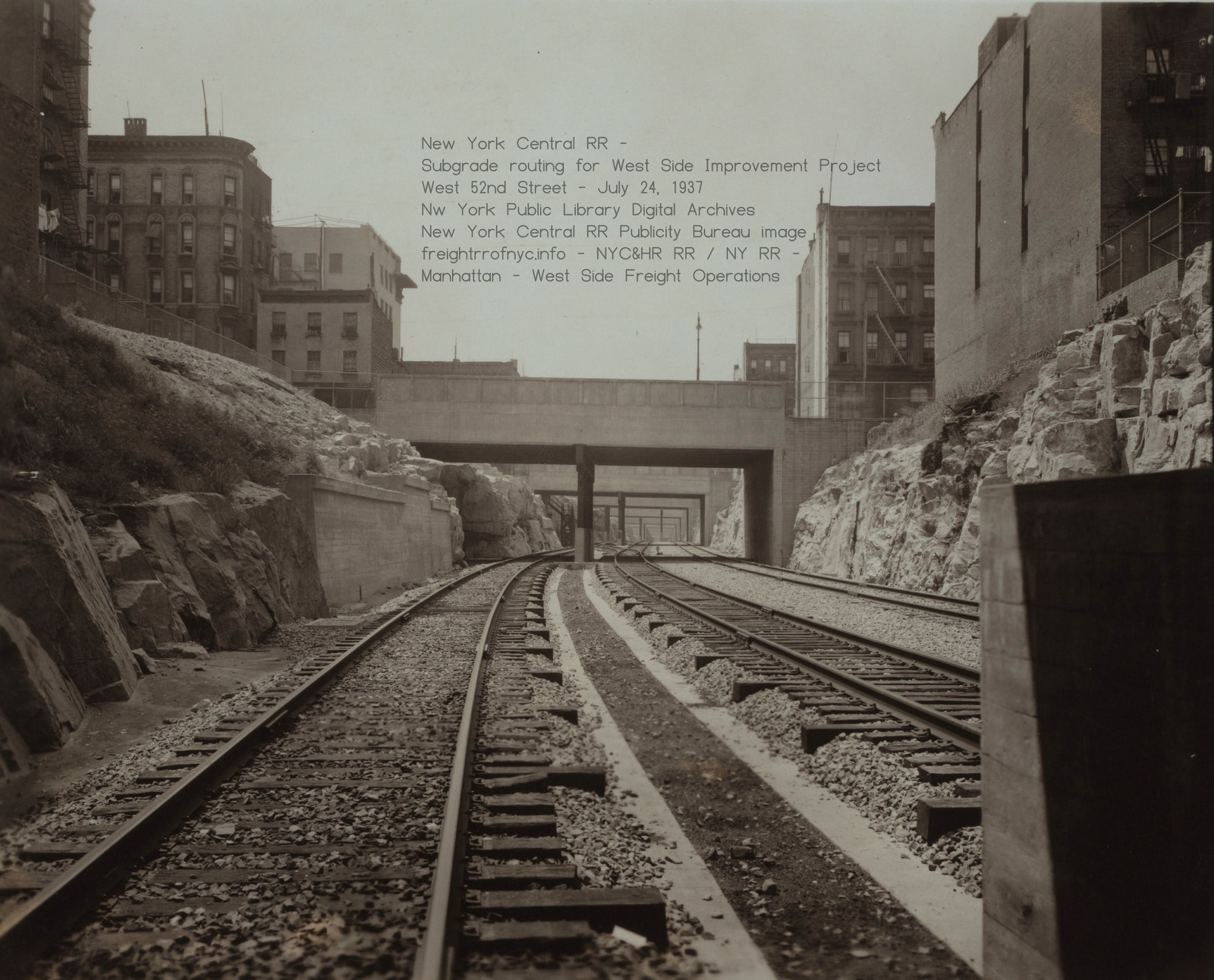

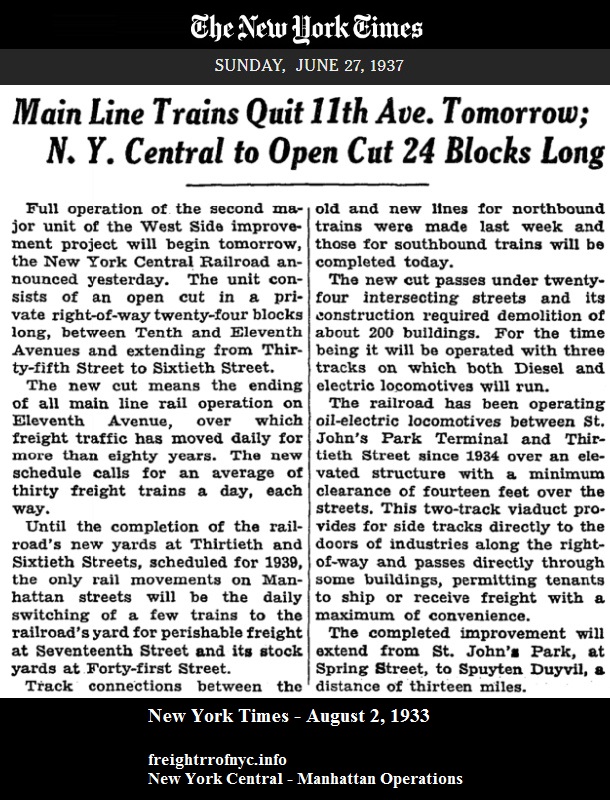

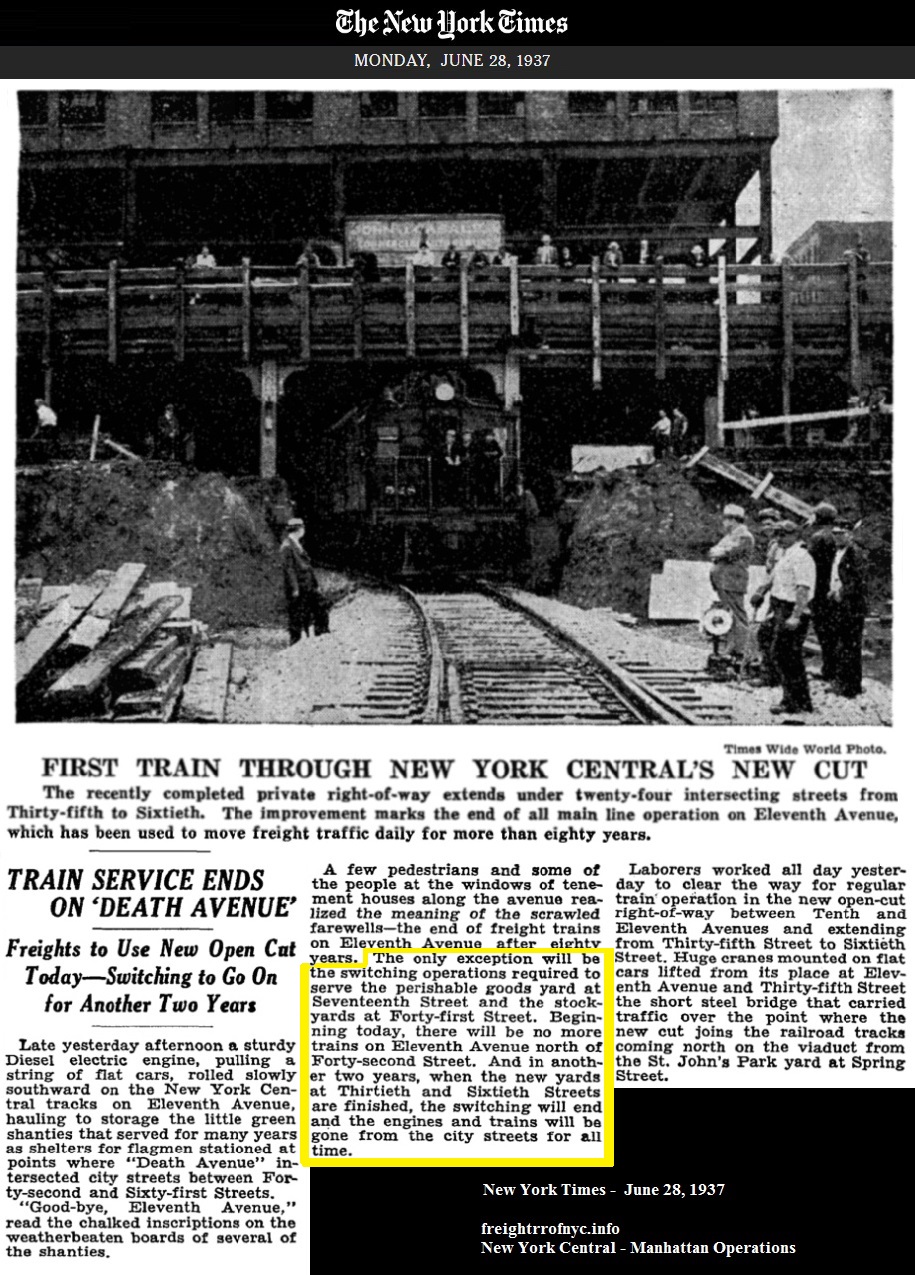

| New York Times article compilation of West Side Improvement - Riverside added | 10/19/2025 | Back to the West Side Improvement Project - Riverside Park 1929-1934 |

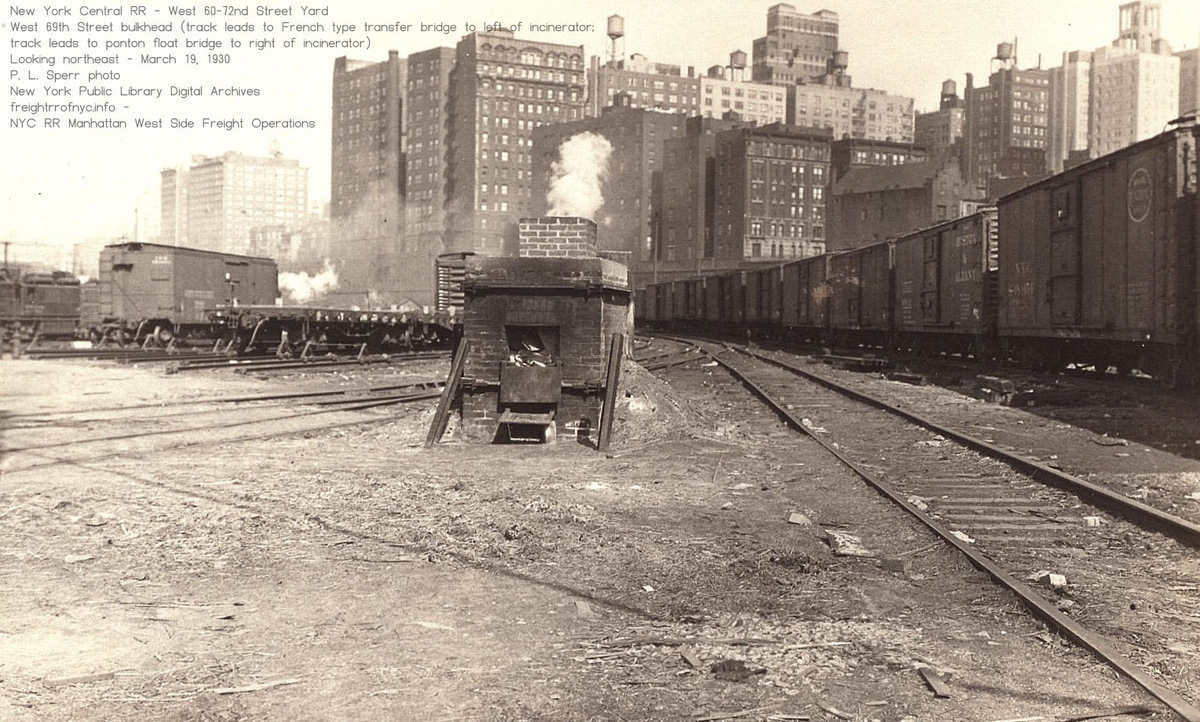

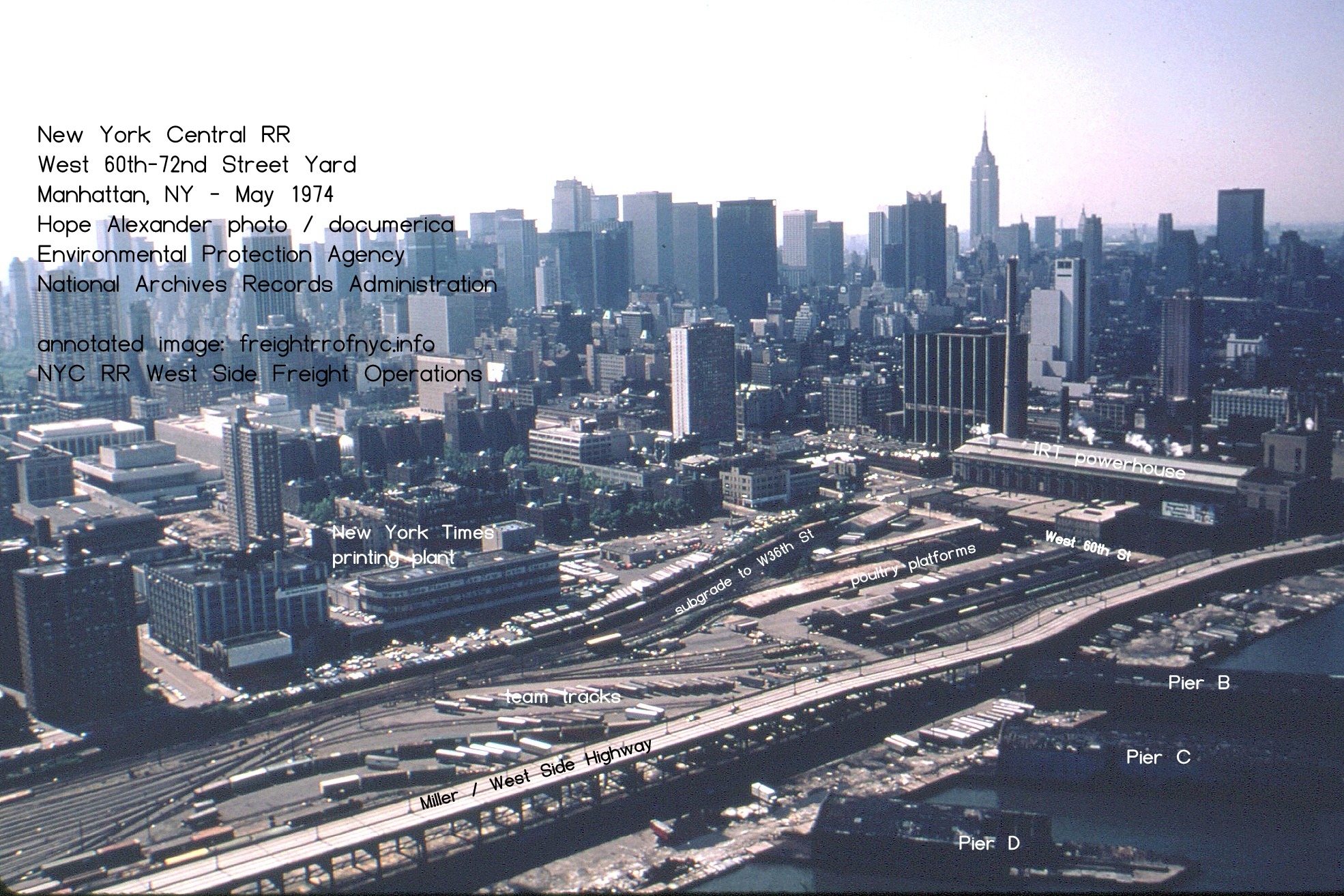

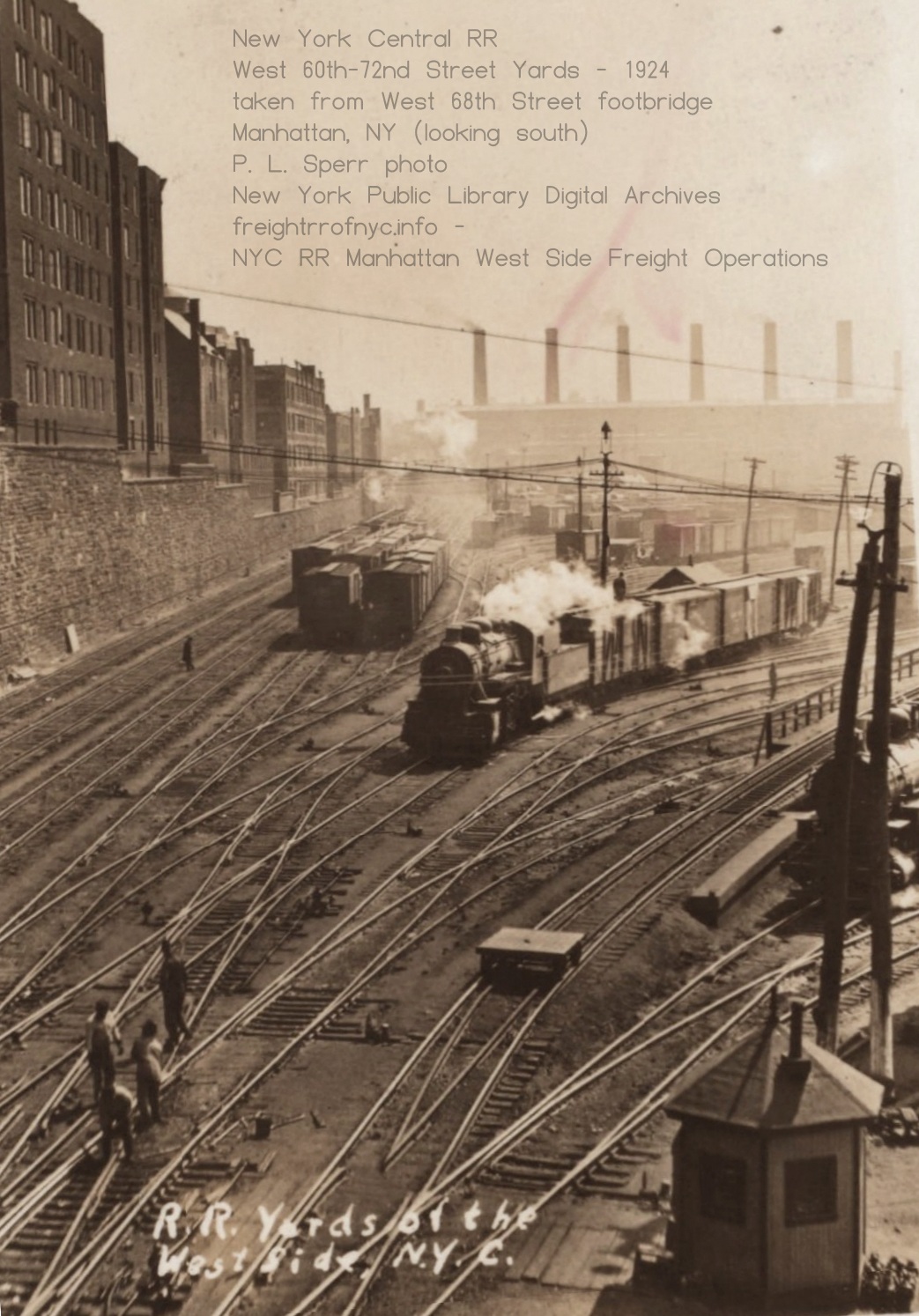

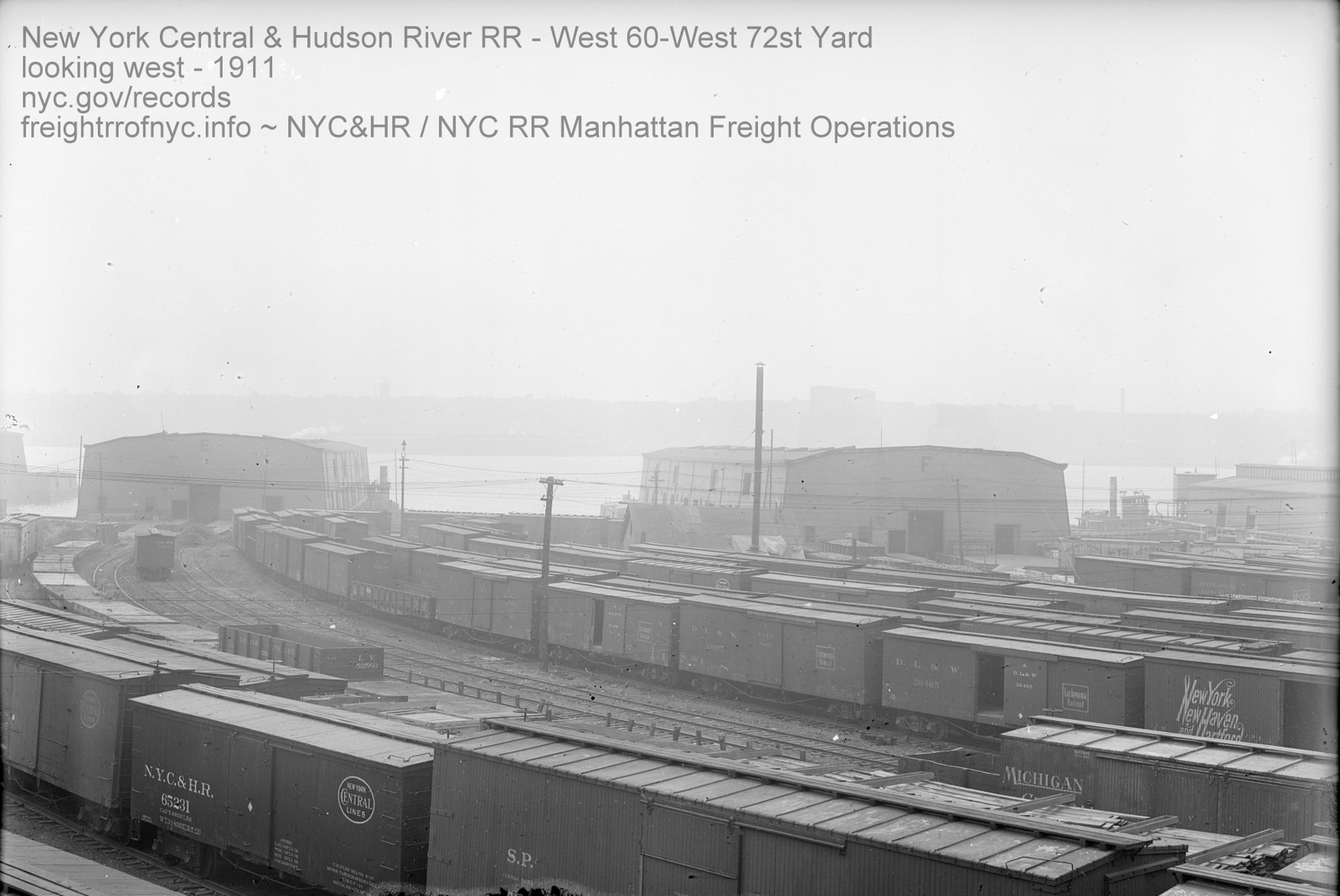

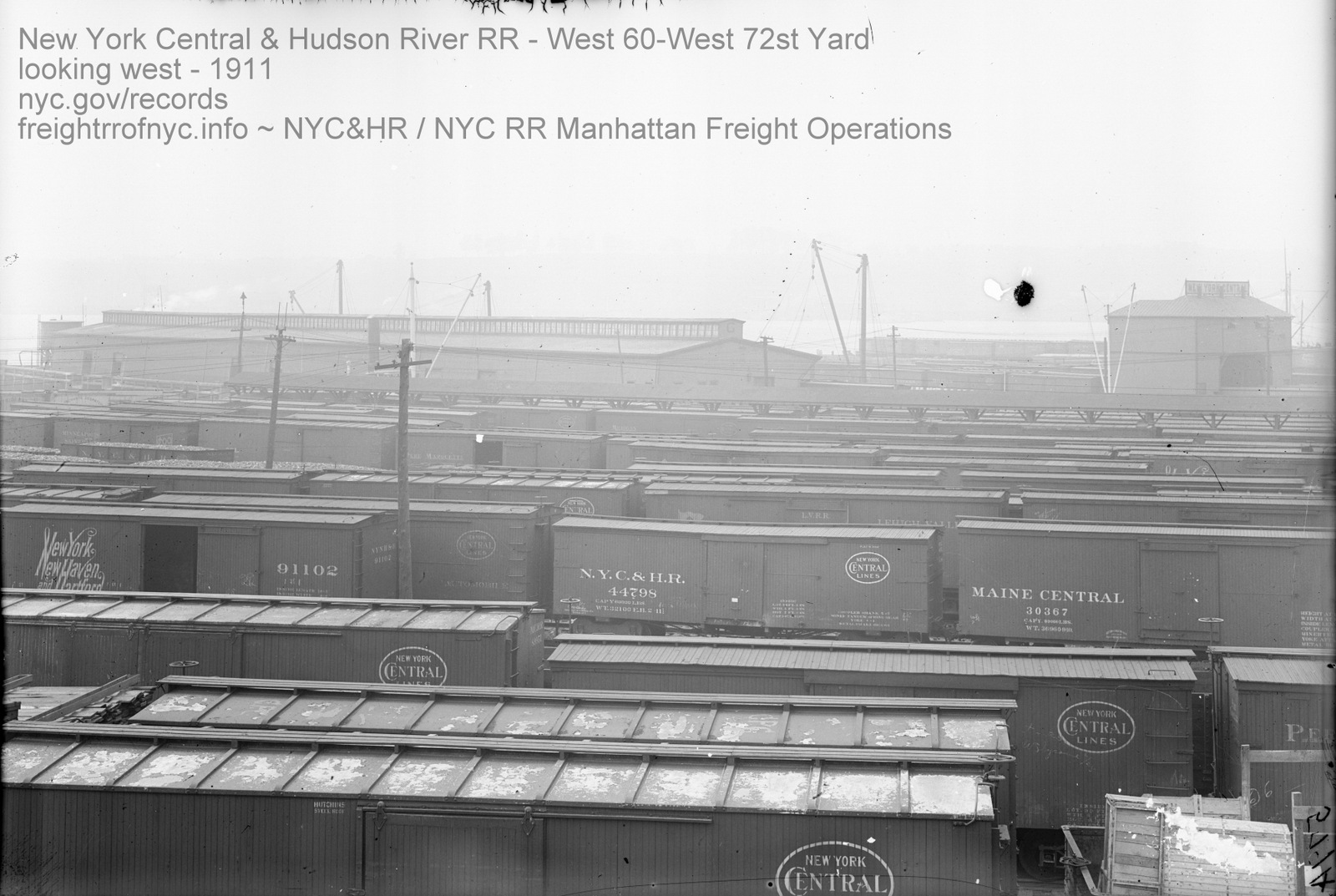

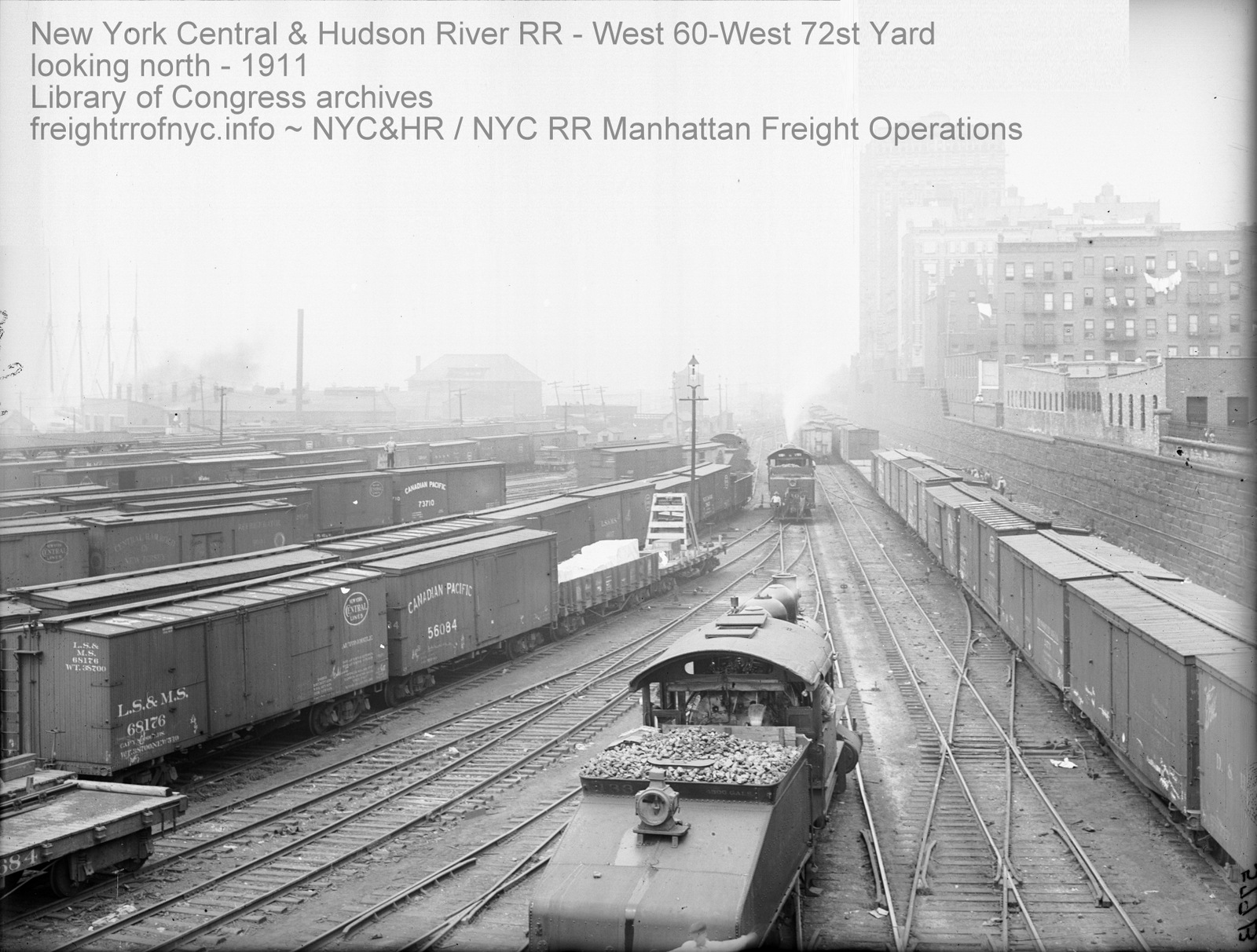

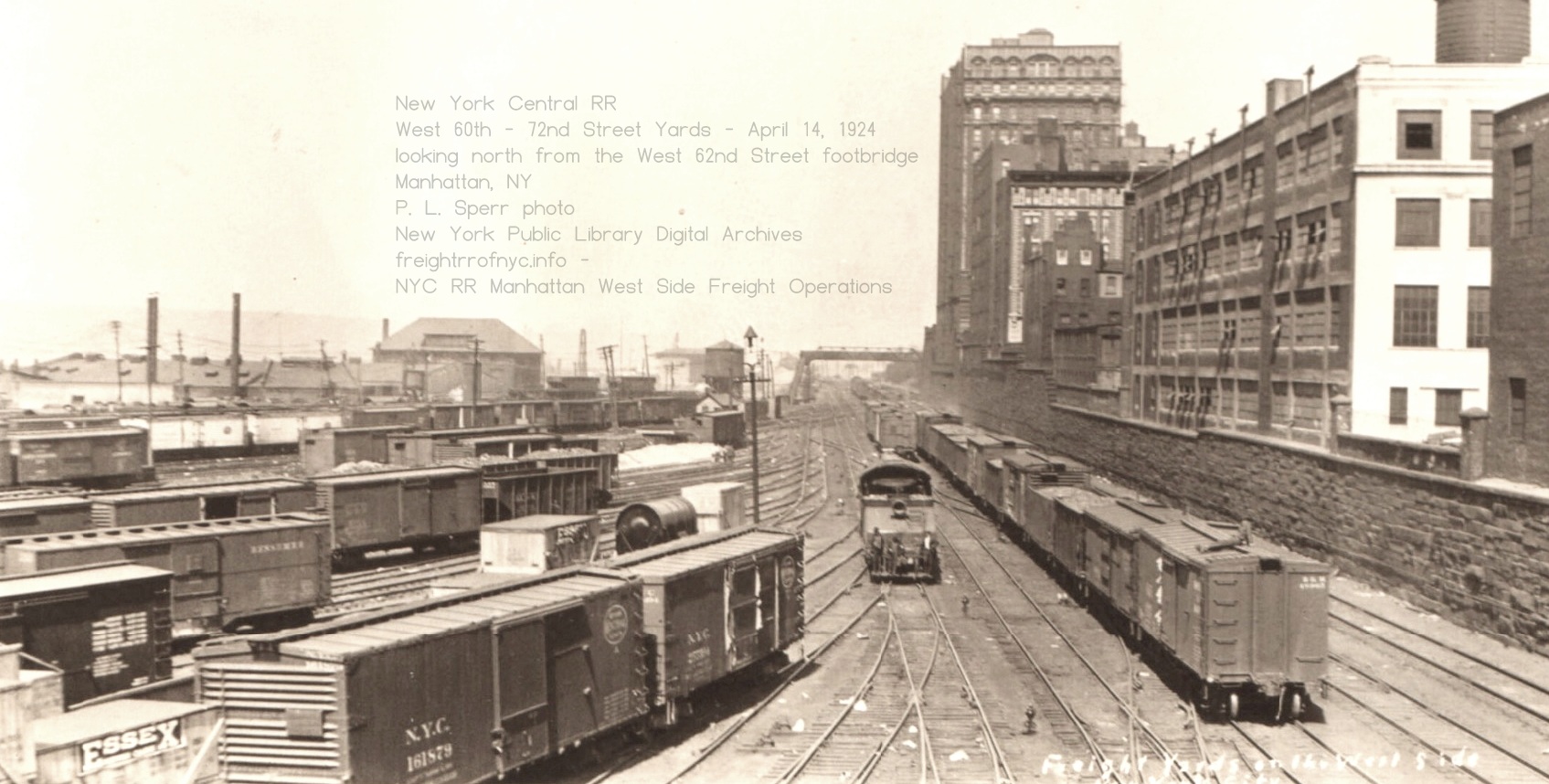

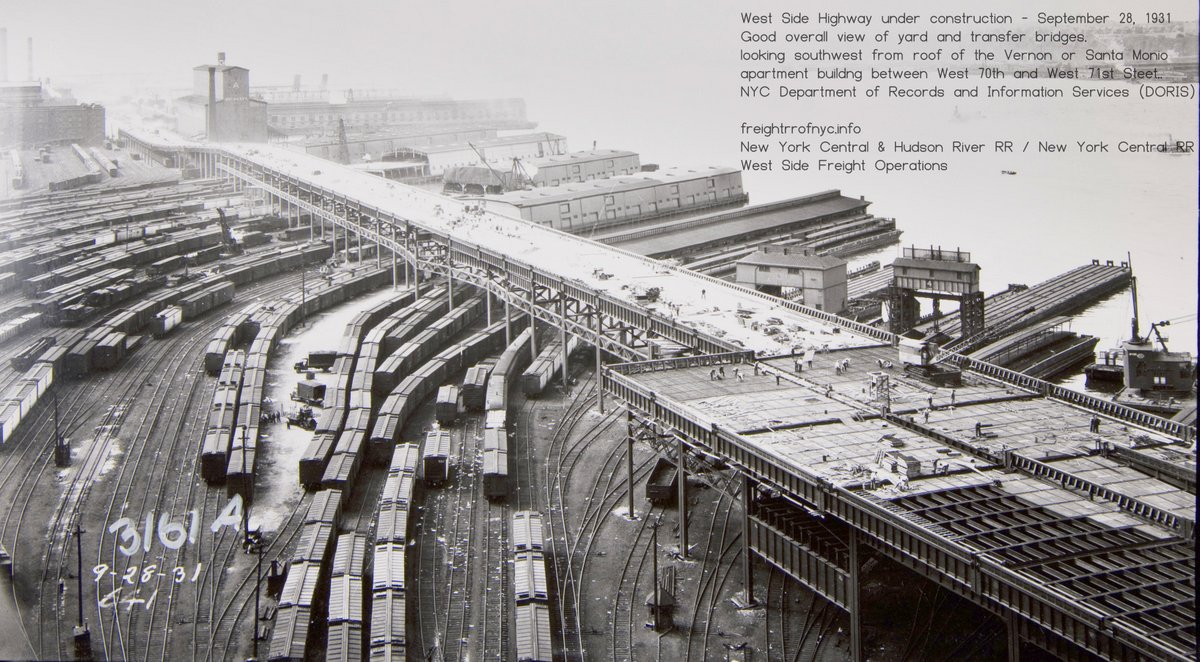

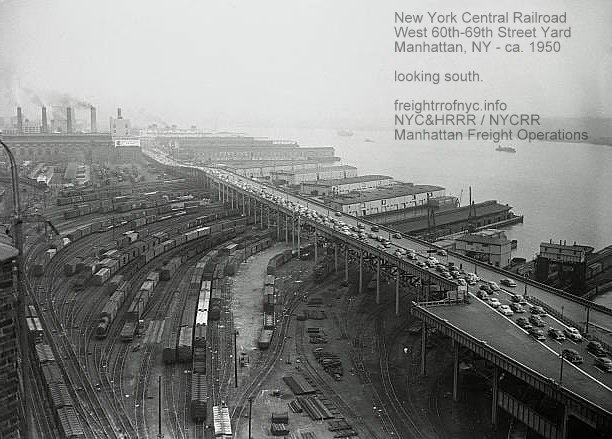

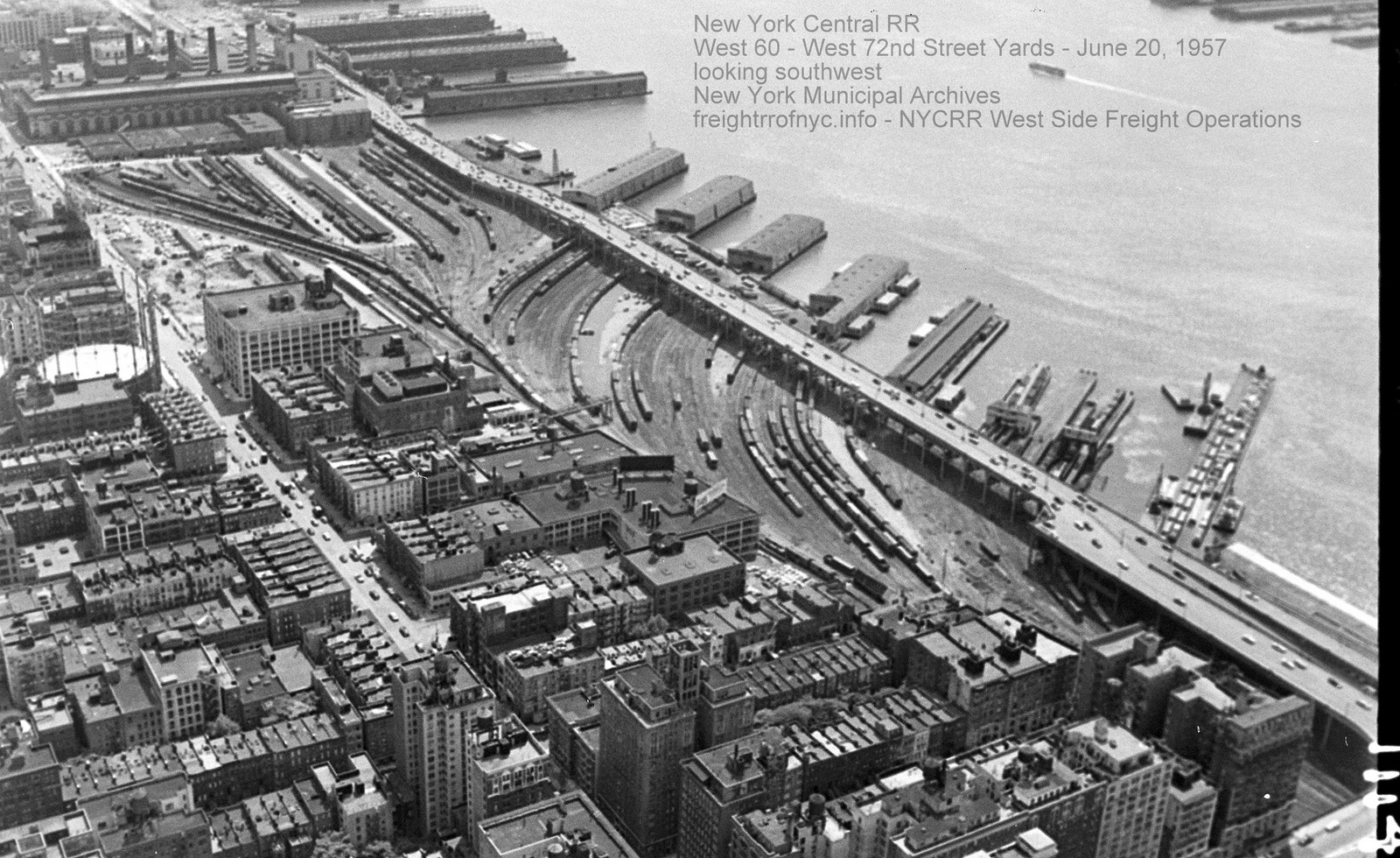

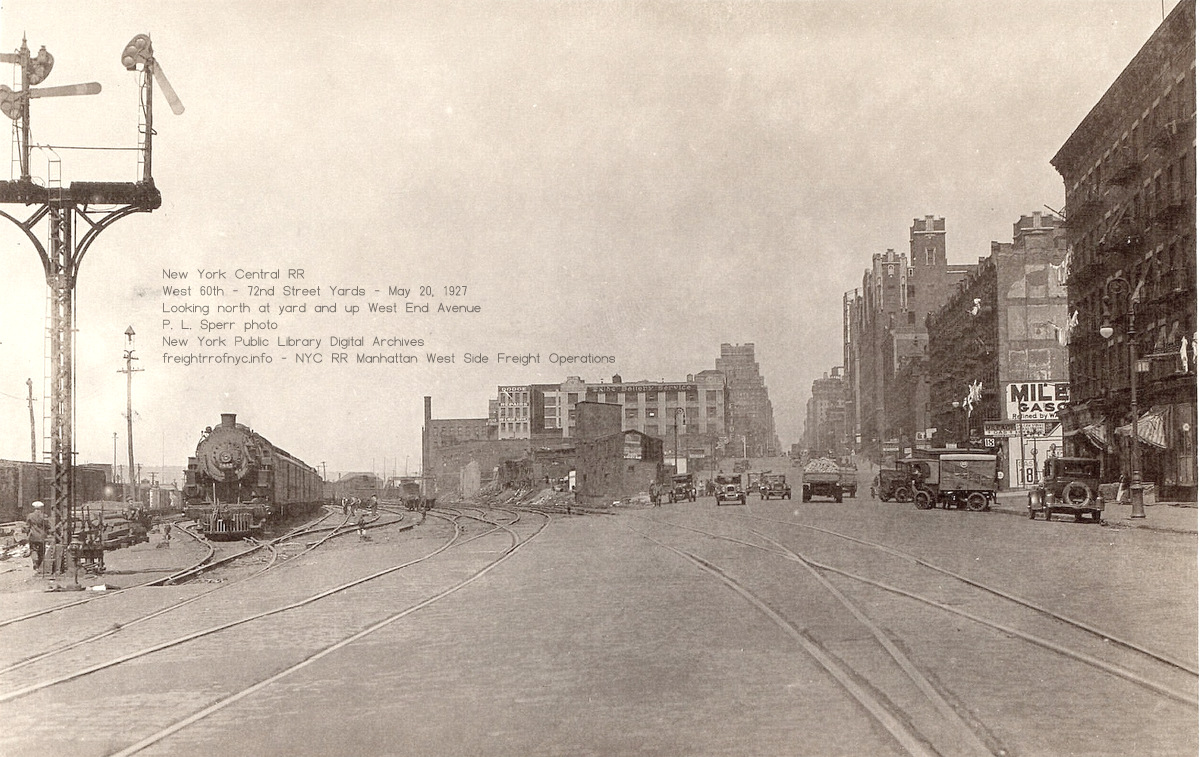

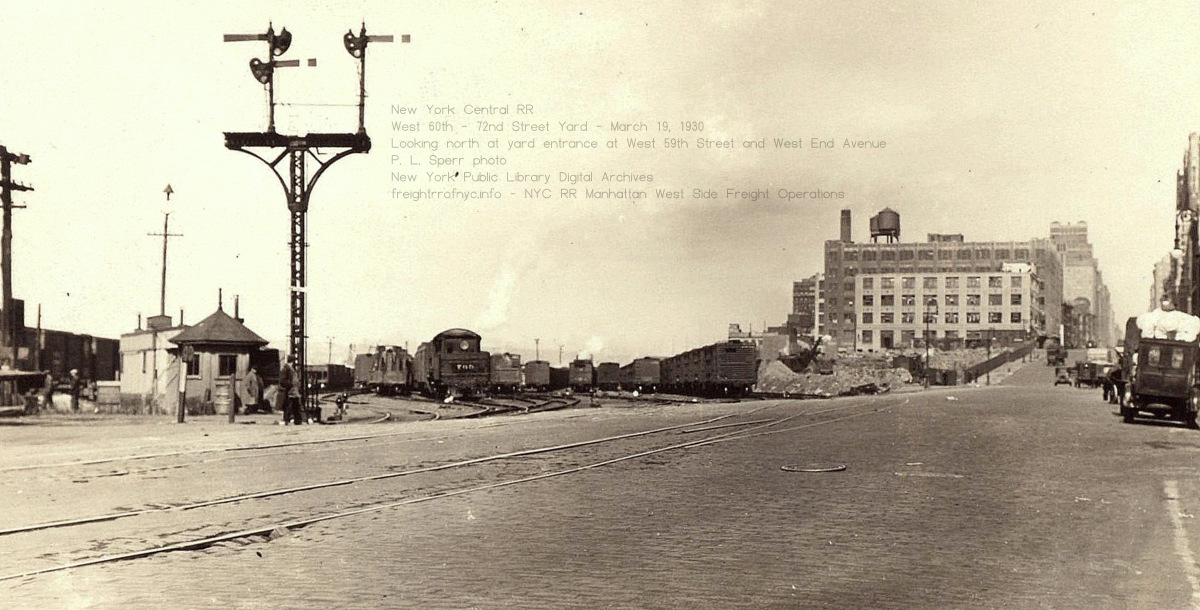

| Pier description and annotated map added | 10/16/2025 | West 60th-72nd Street Yards & Roundhouse |

| All maps moved to dedicated page | 10/15/2025 | Page 3: Maps; Property, Port Terminals; Track and Valuation |

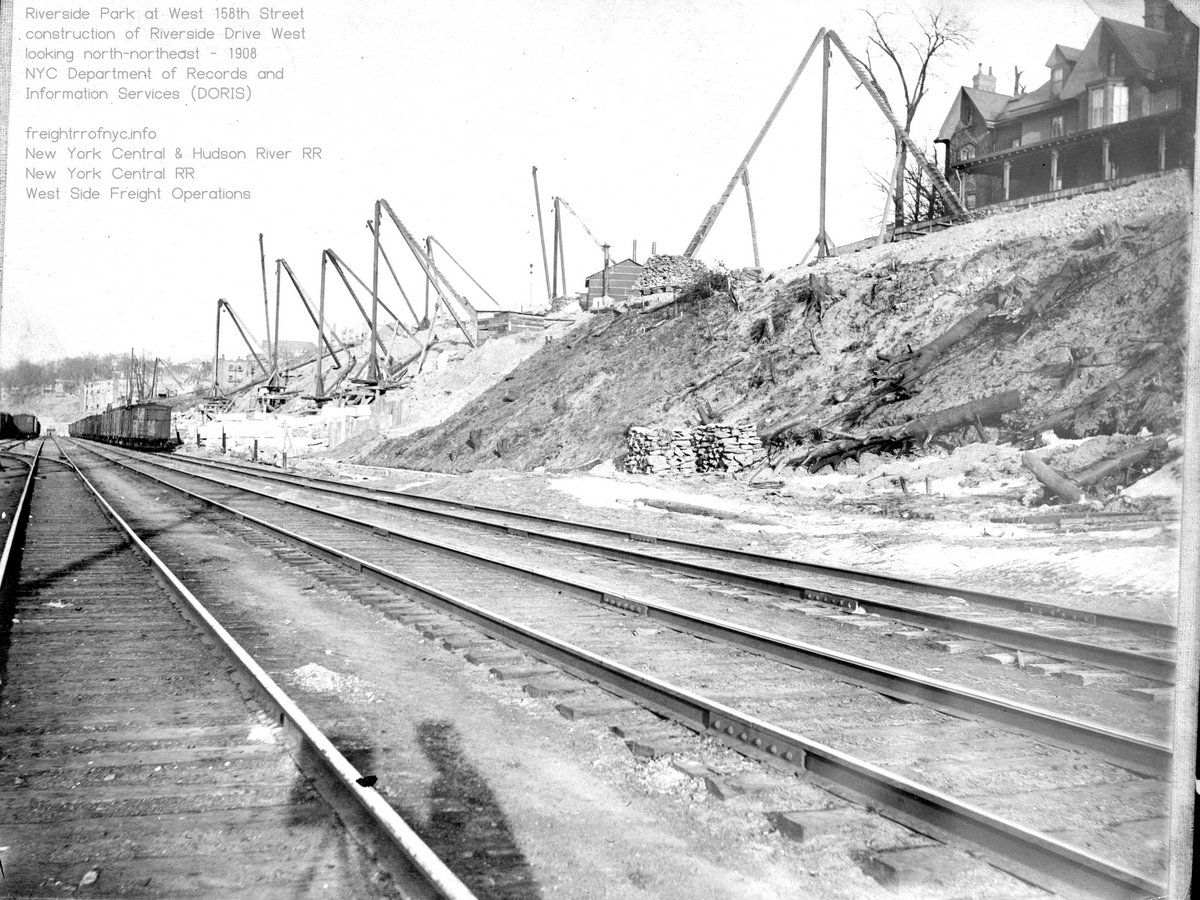

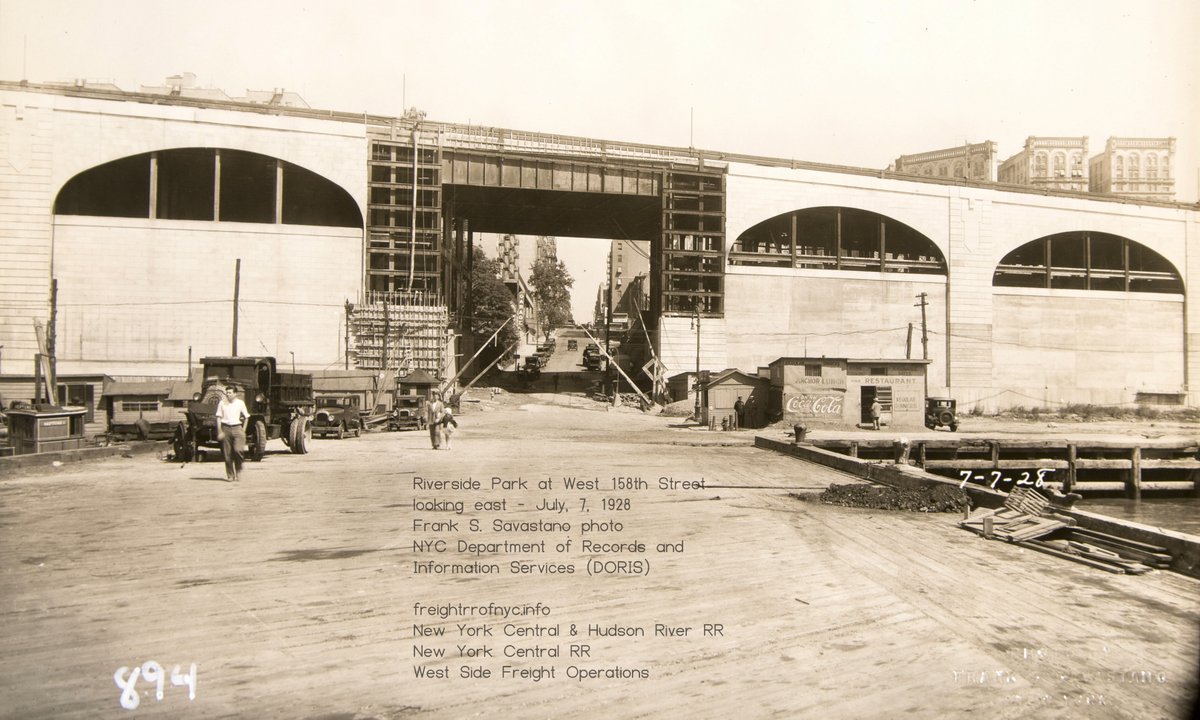

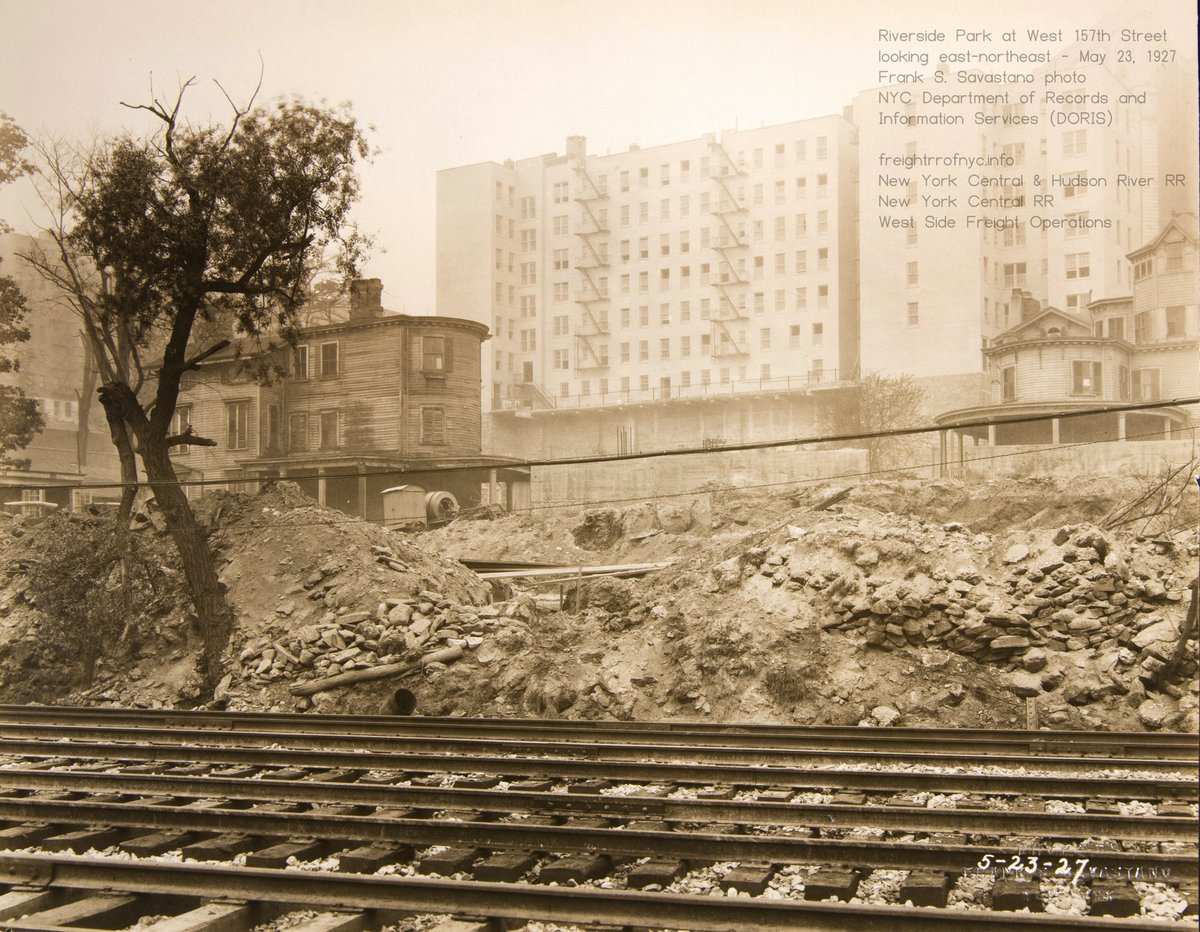

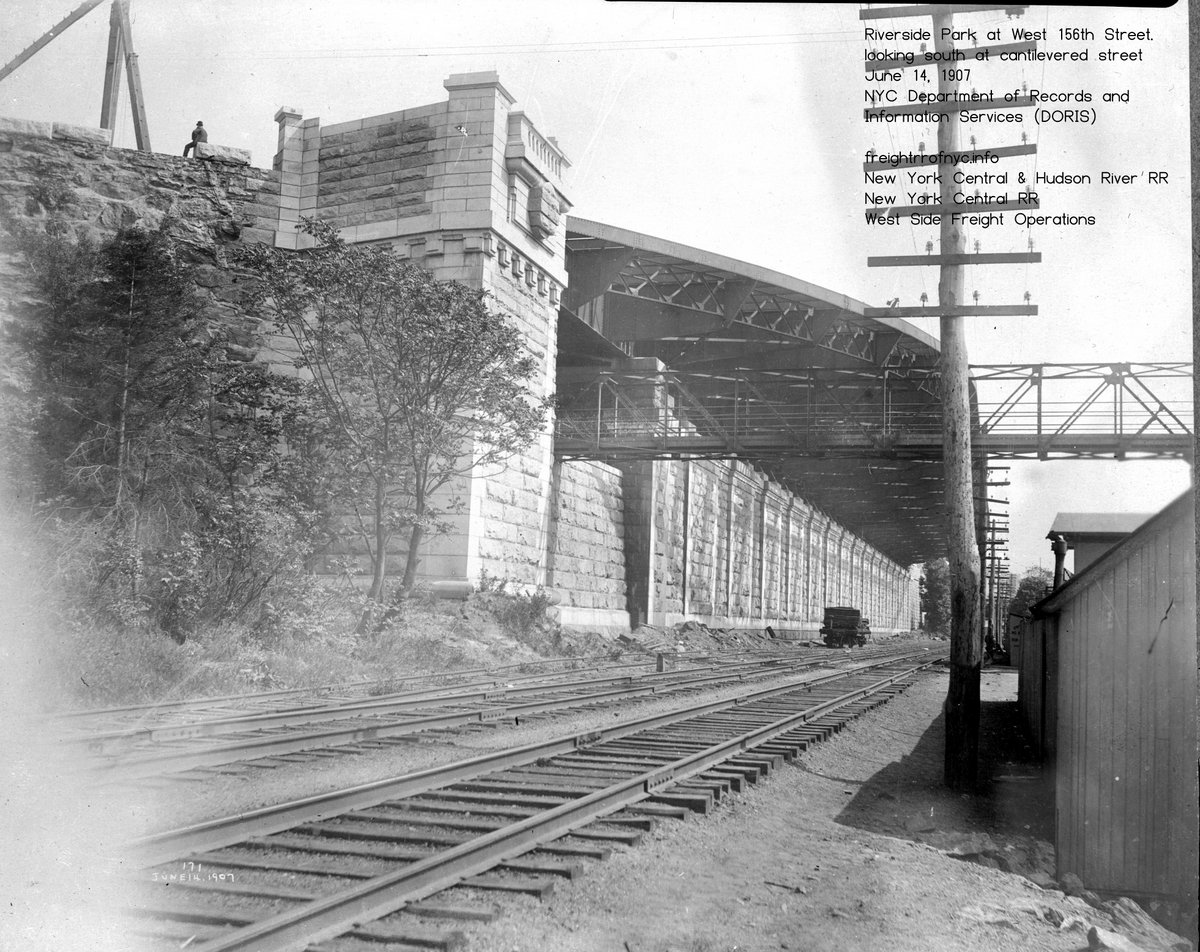

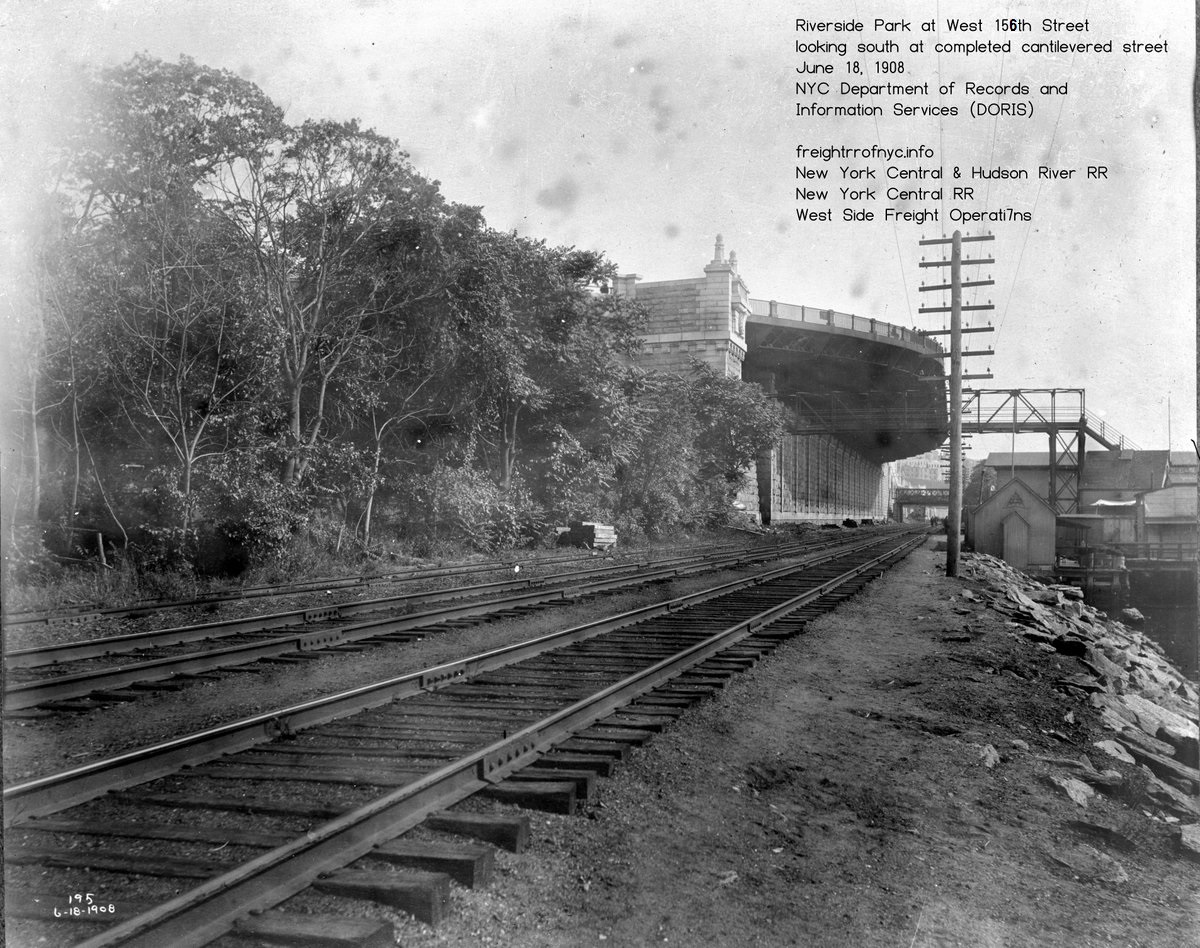

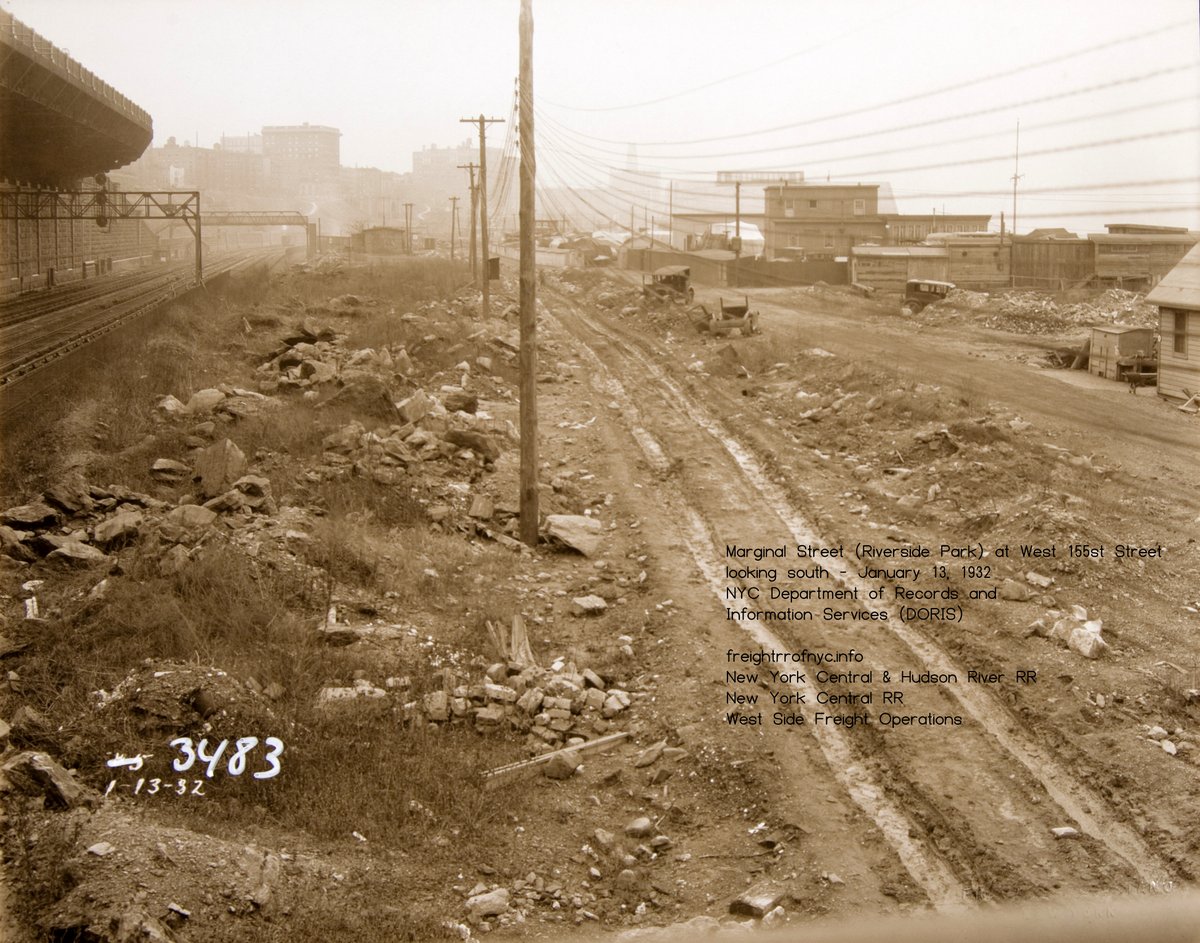

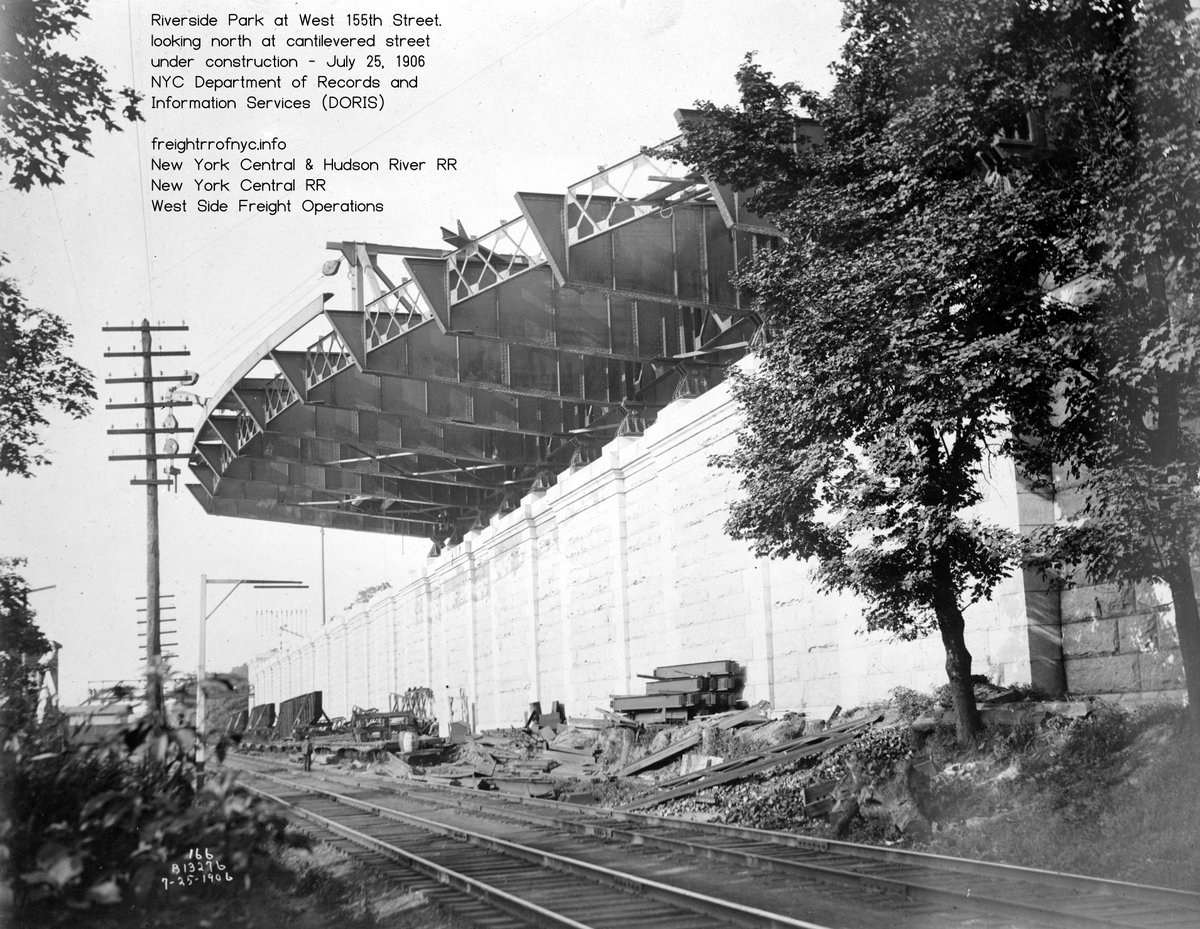

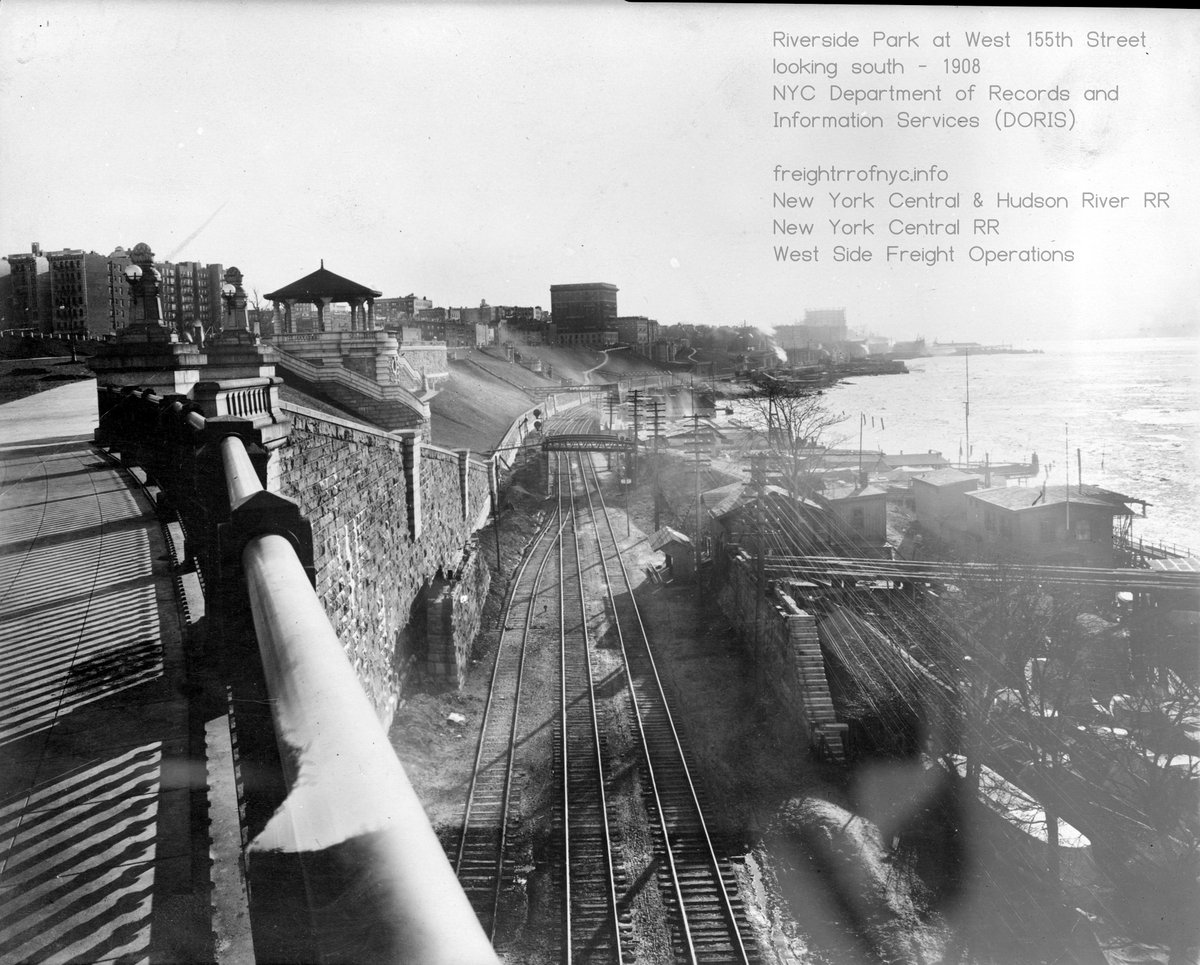

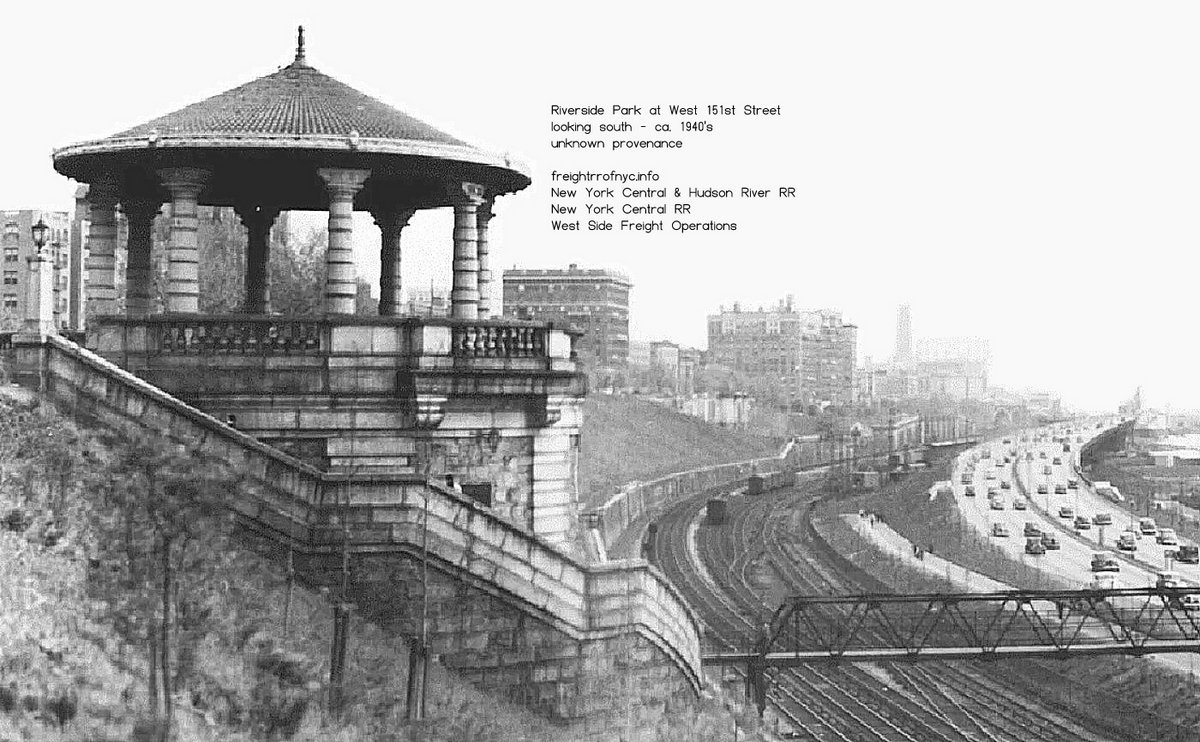

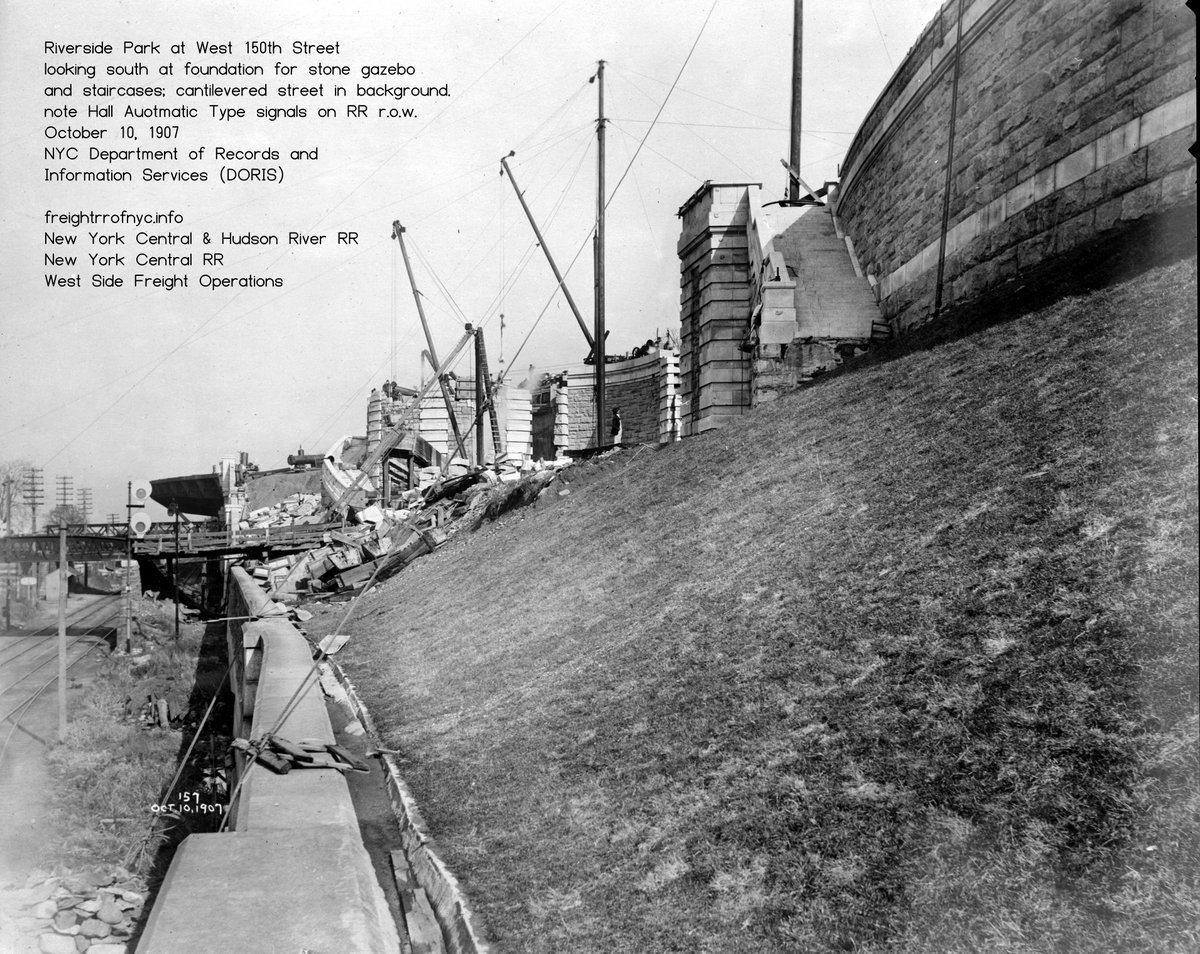

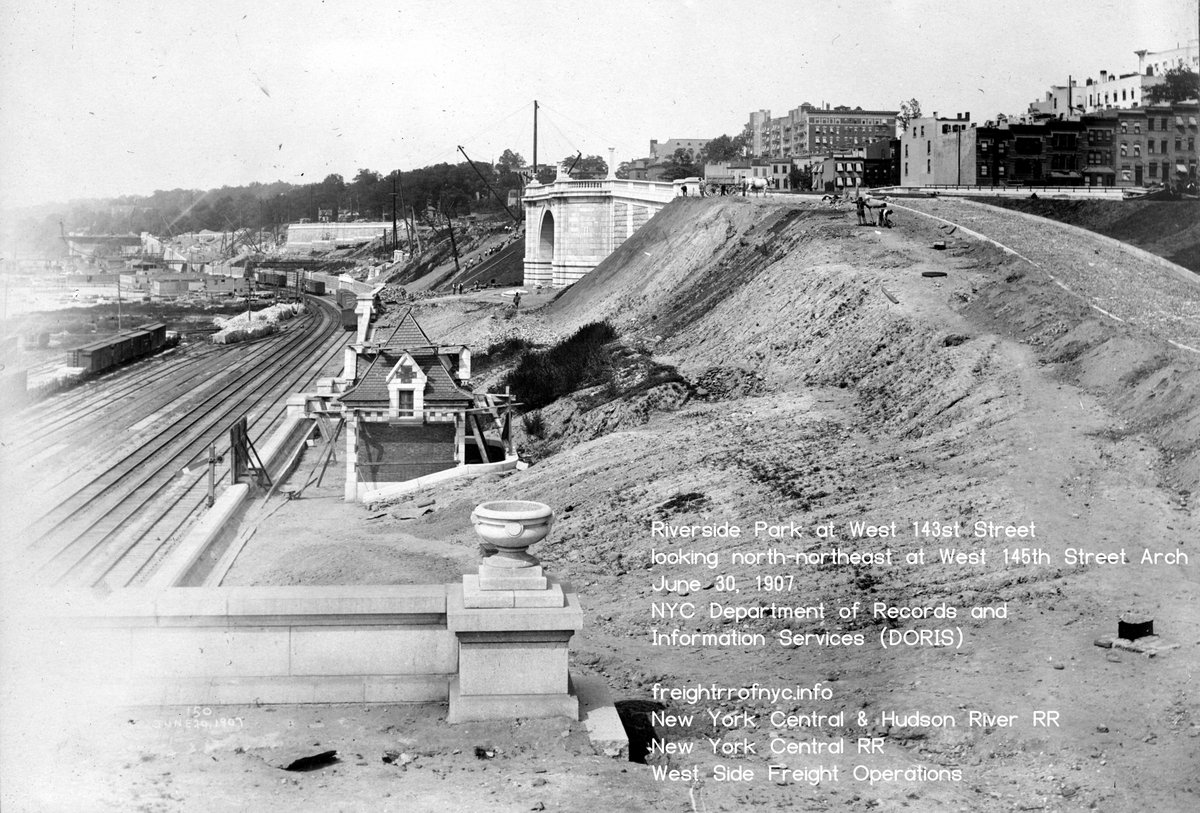

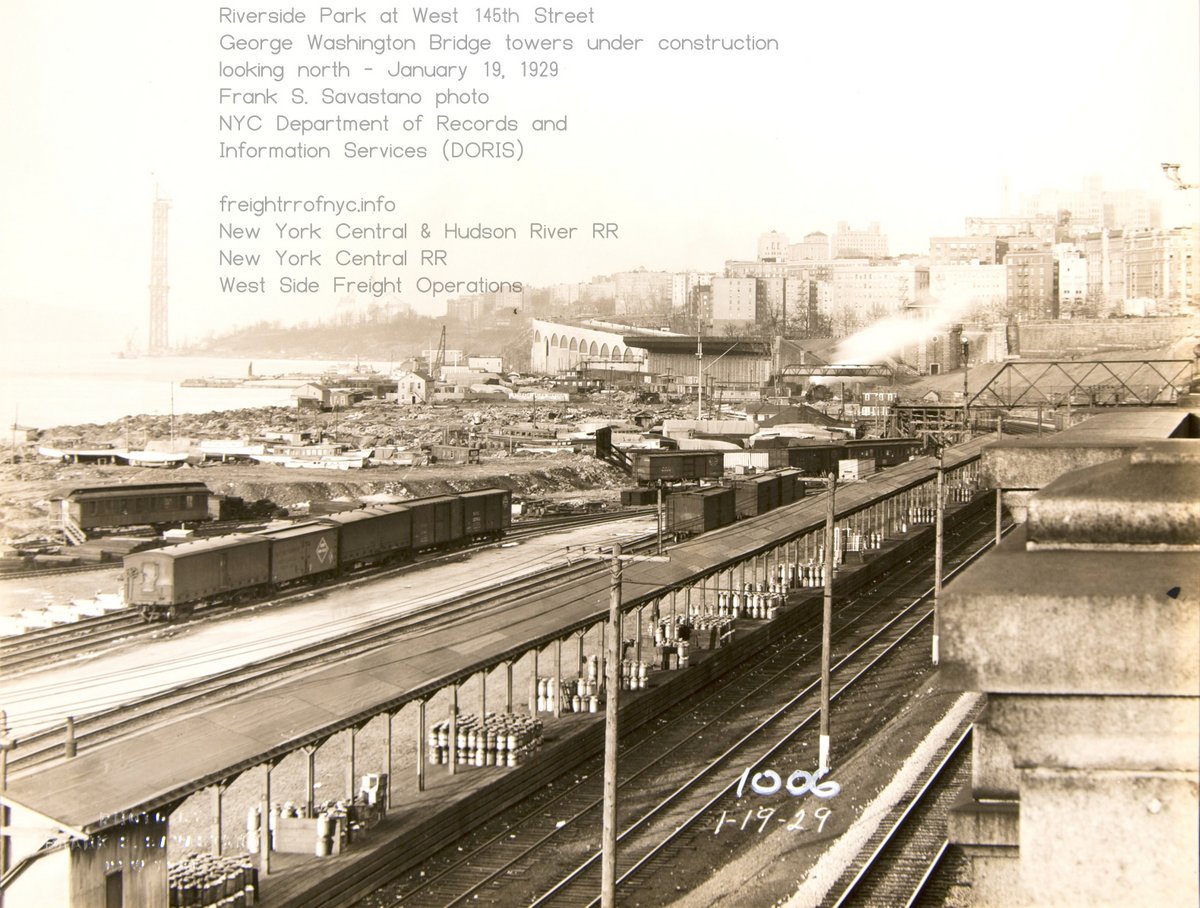

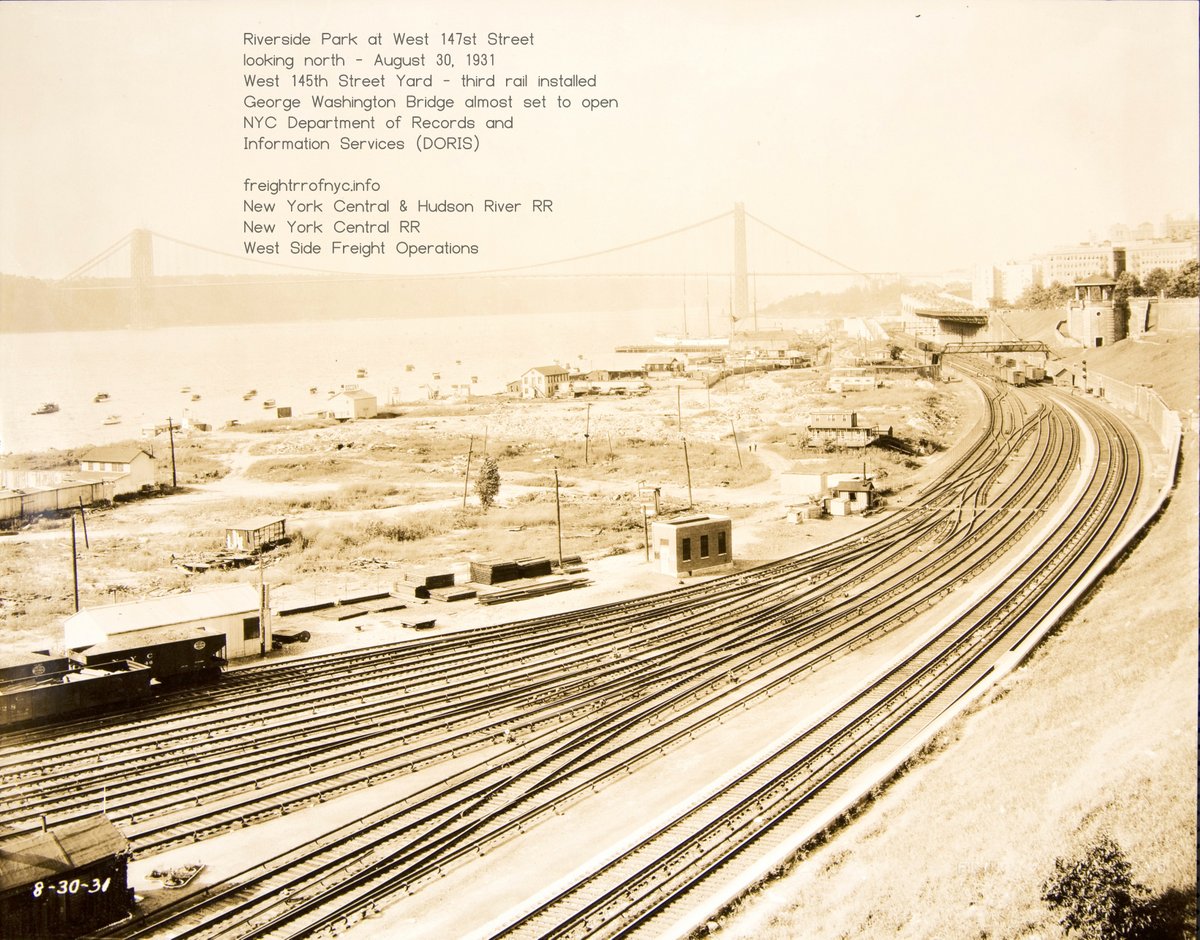

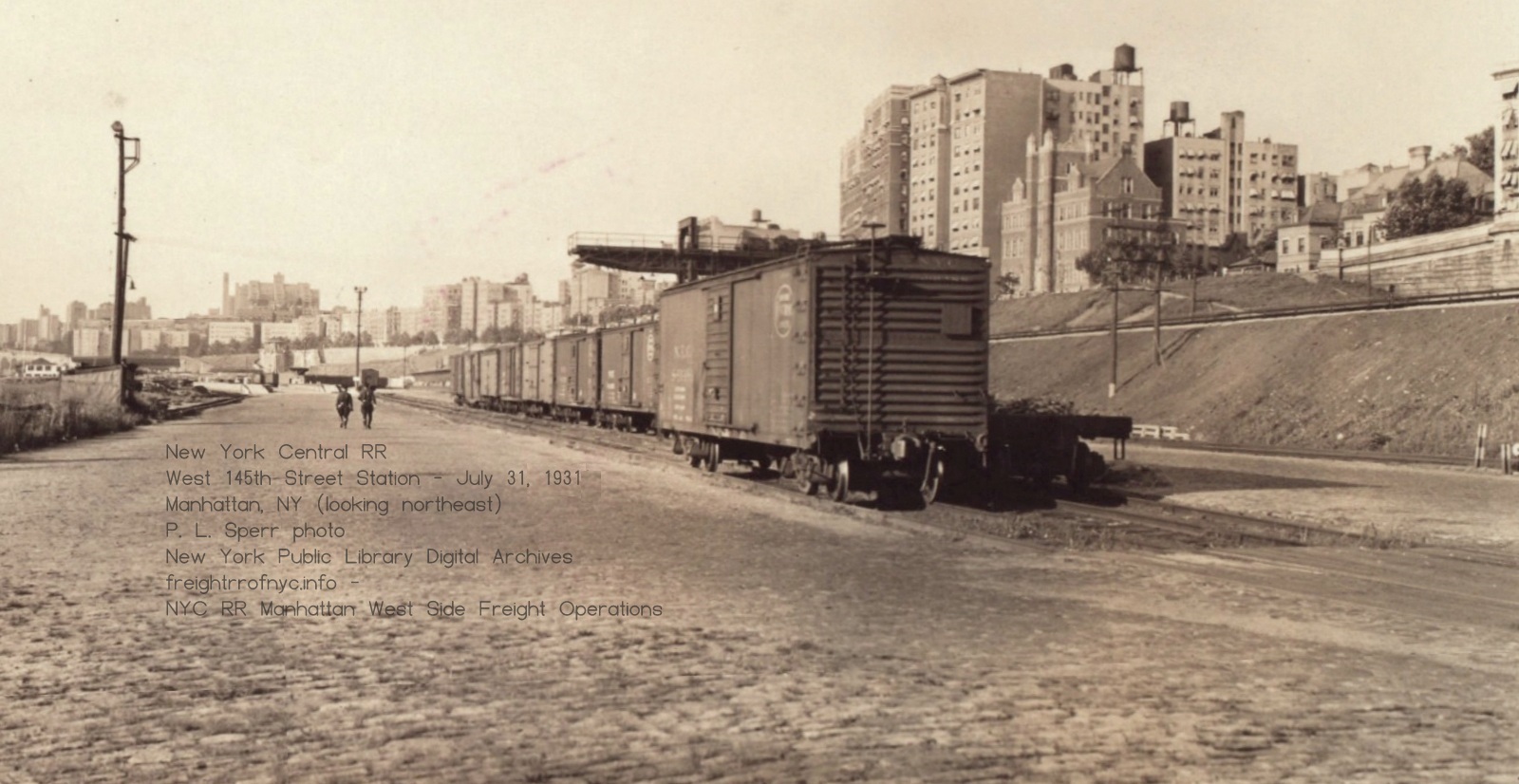

| West 155th through 145th Street images added | 10/13/2025 | West 155th Street West 145th Street |

| April 1966 Aerials of West 30-36th Street Yard May & June 1974 aerials of West 60-72nd St Yard added |

10/10/2025 | West 30th-36th Street Yards and Freighthouses West 60th-72nd Street Yard & Roundhouse |

| West 59th Street Freight Station - Pier 99 with trestle added | 10/6/2025 | West 59th Street Freight Station - Pier 99 |

| Steam Locomotive restrictions and bans in Manhattan moved to own page | 9/16/2025 | Steam Locomotive Operations / Restrictions & Bans in Manhattan |

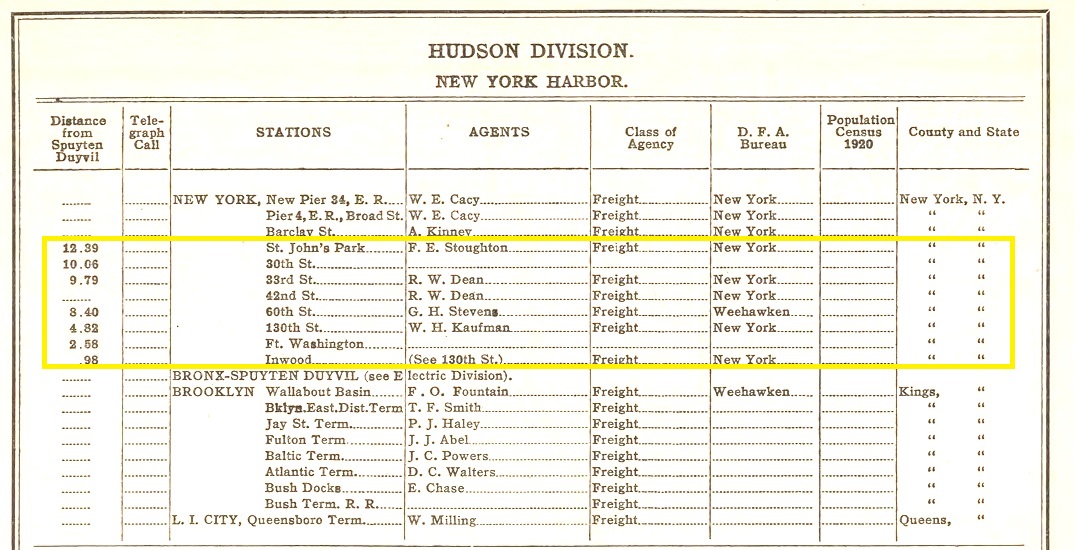

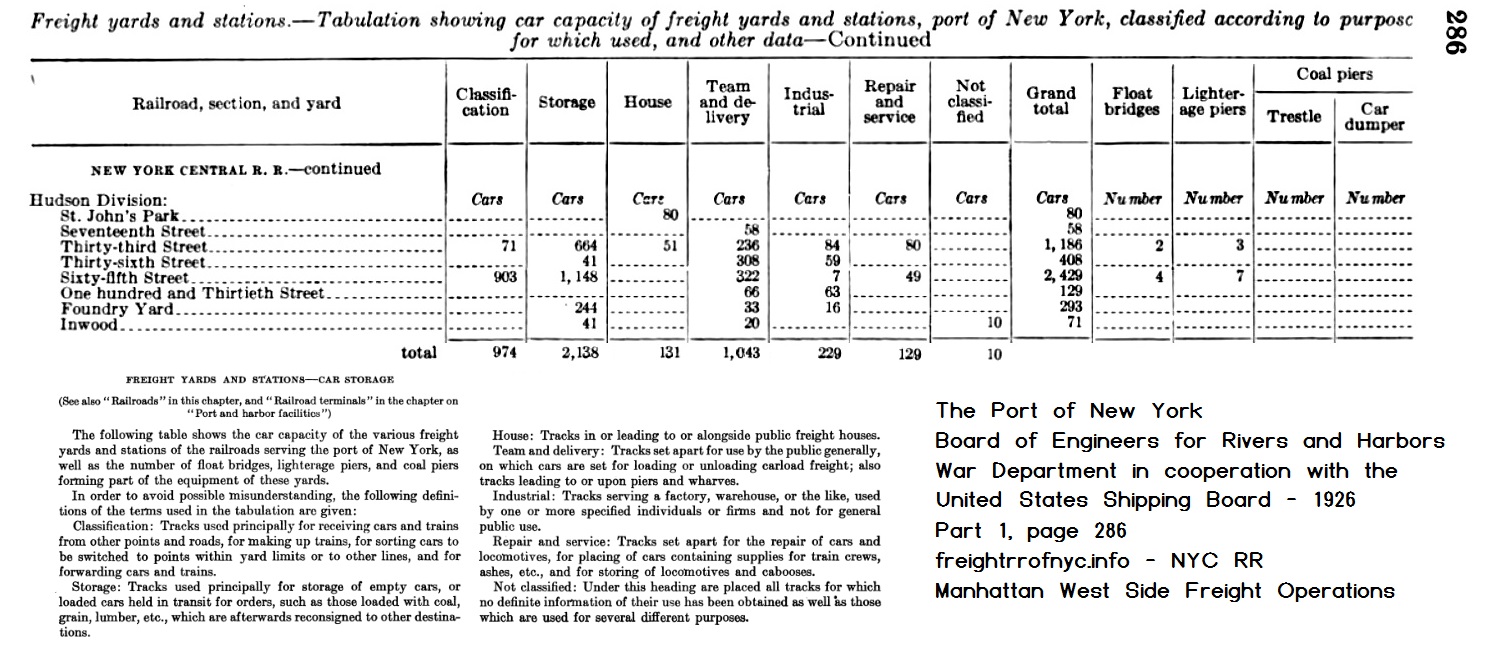

| Table of Yard Capacities, New York Central Hudson Division; Manhattan, 1926 | 9/14/2025 | 1850 - 1968: New York Central Facilities & Service in Manhattan |

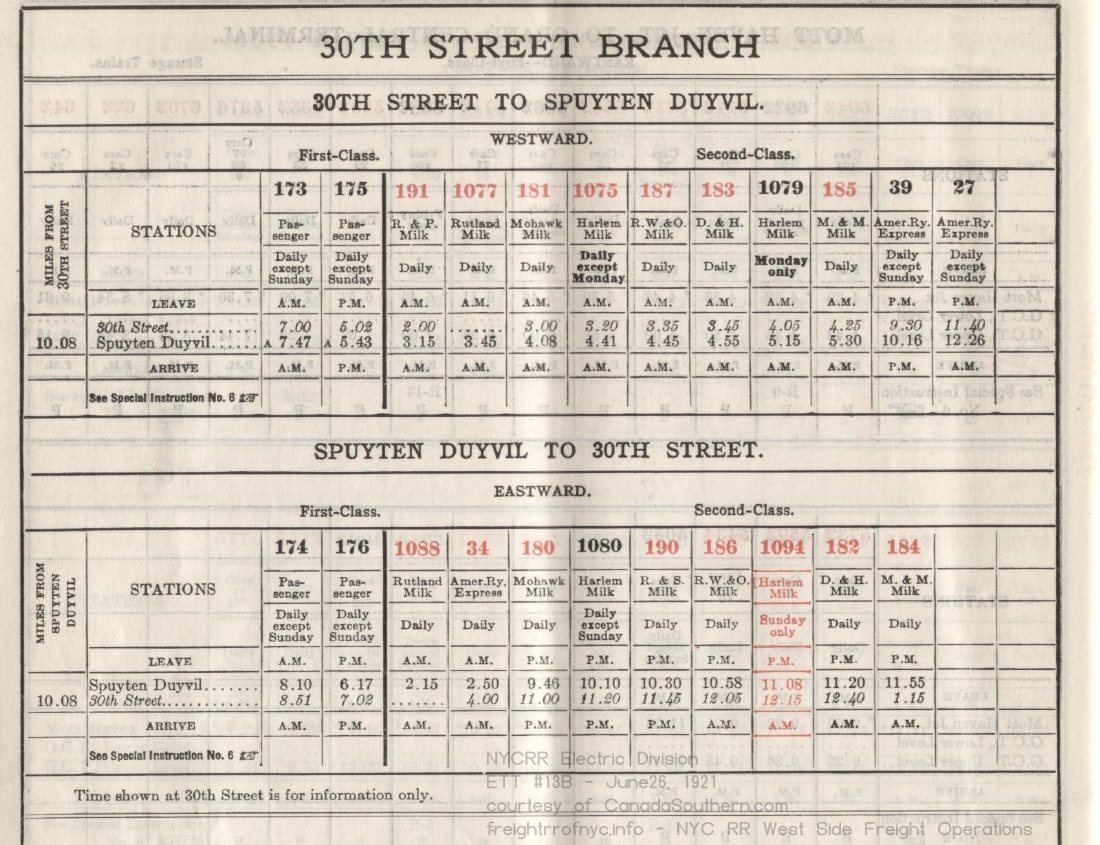

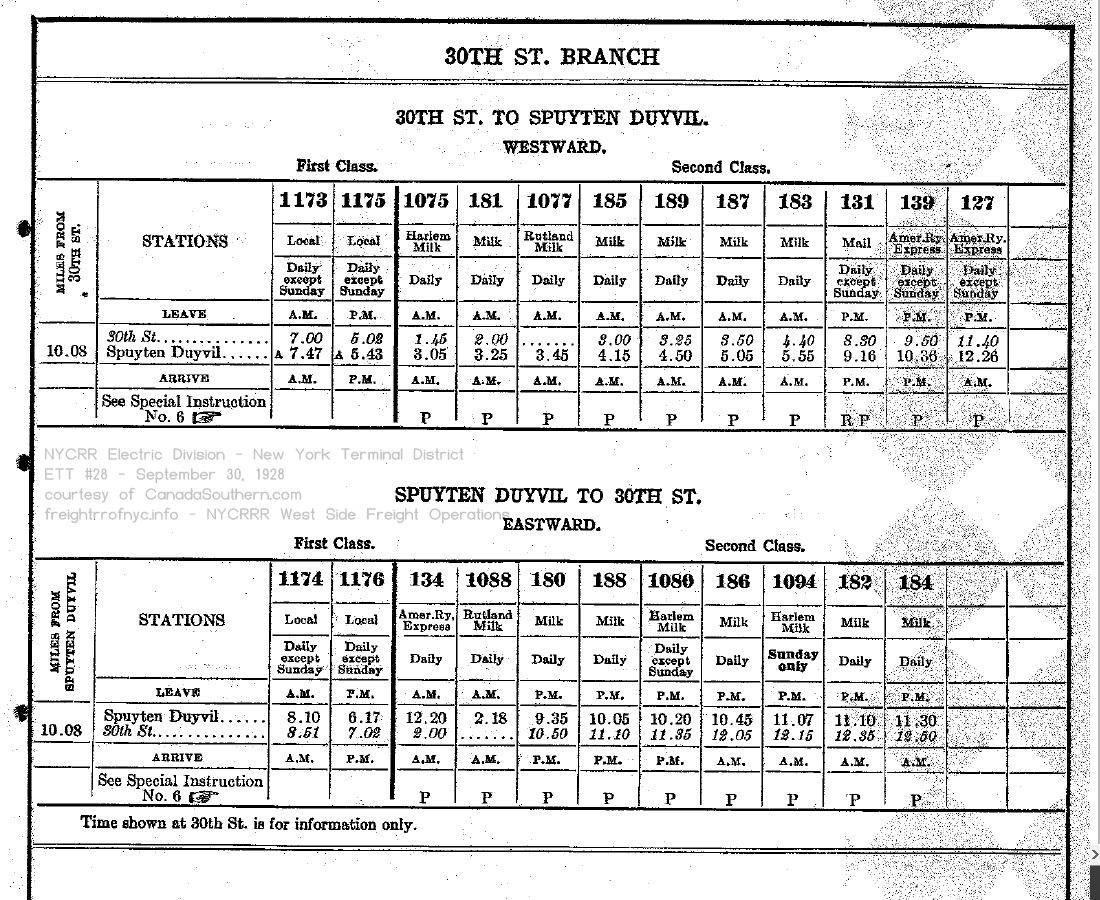

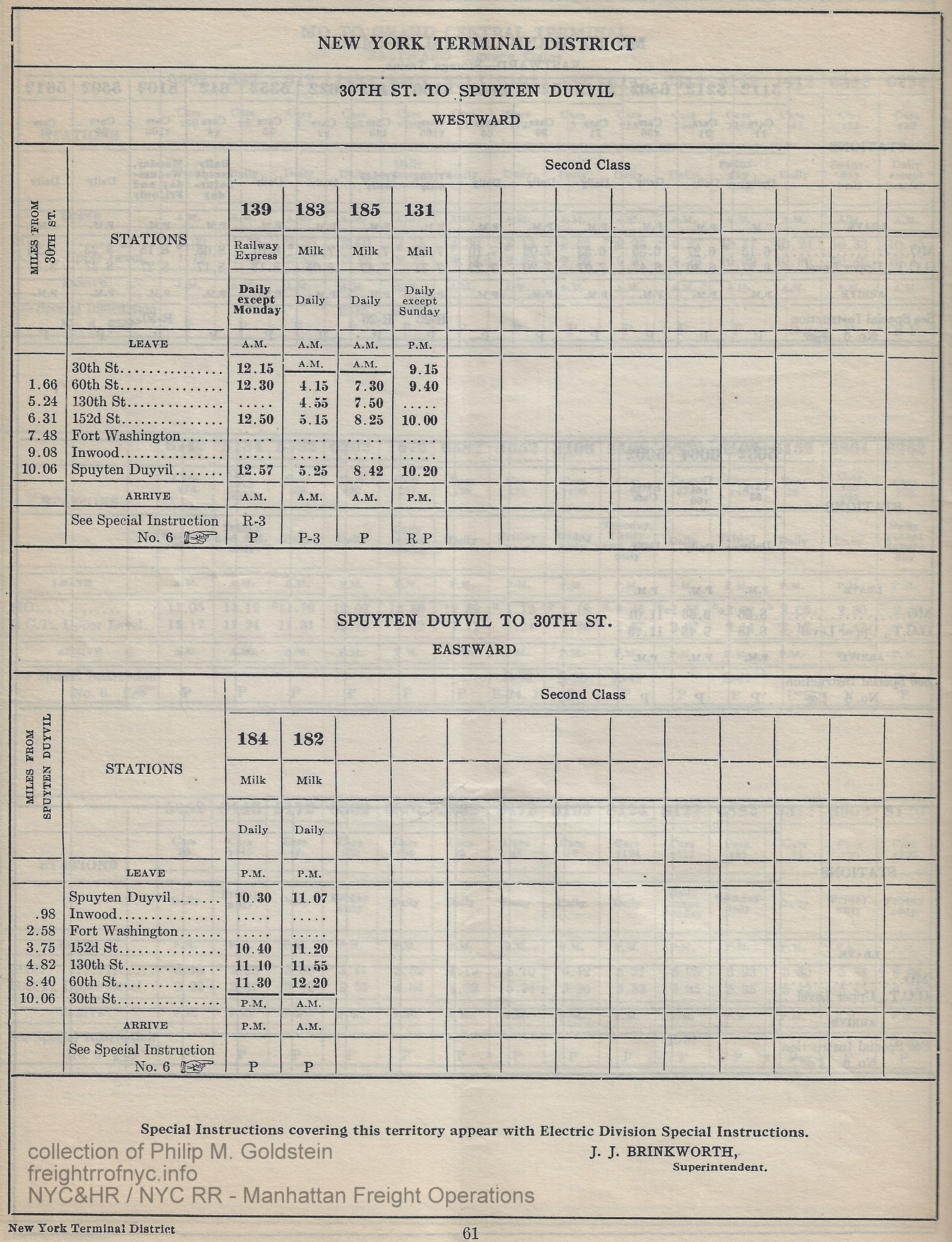

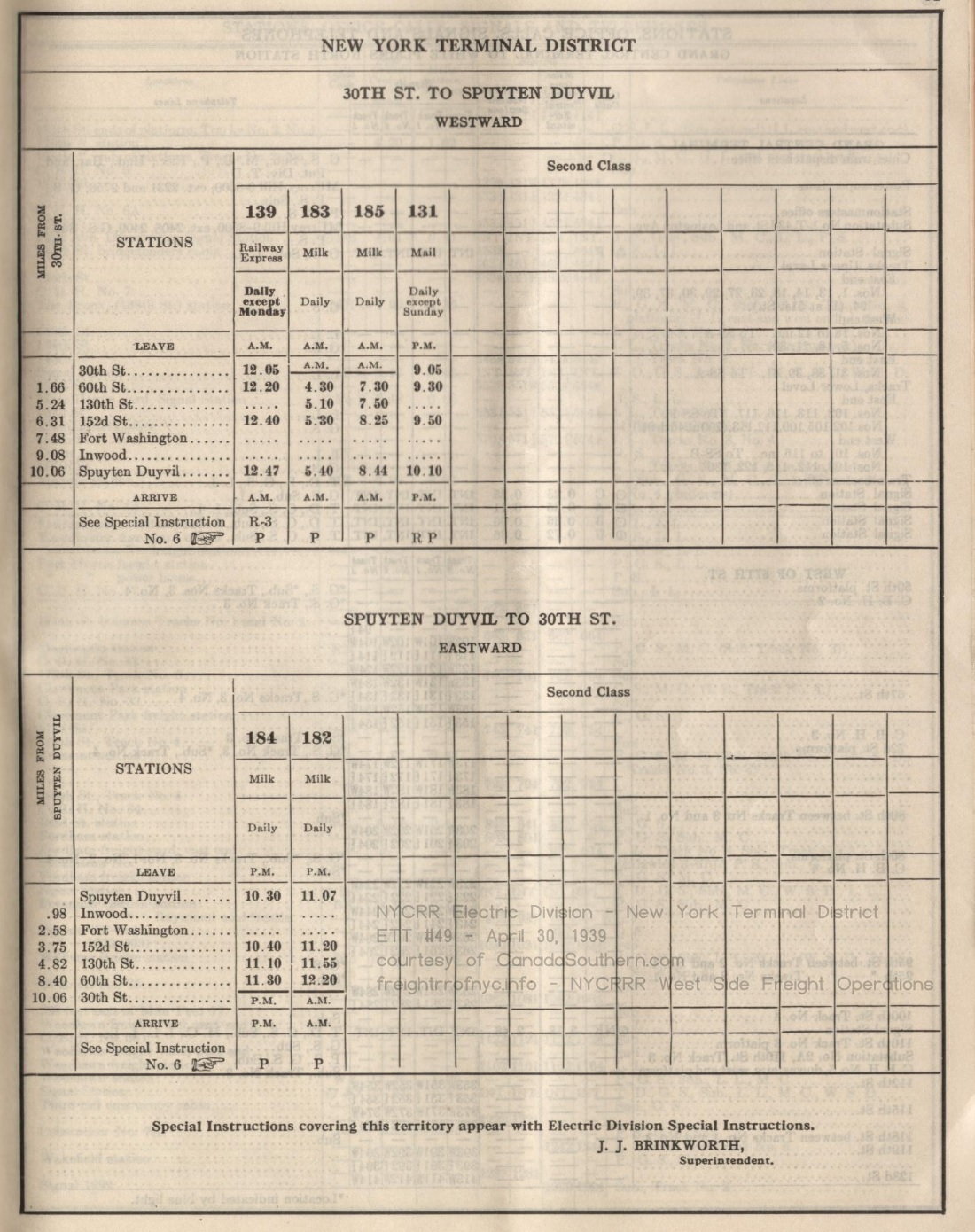

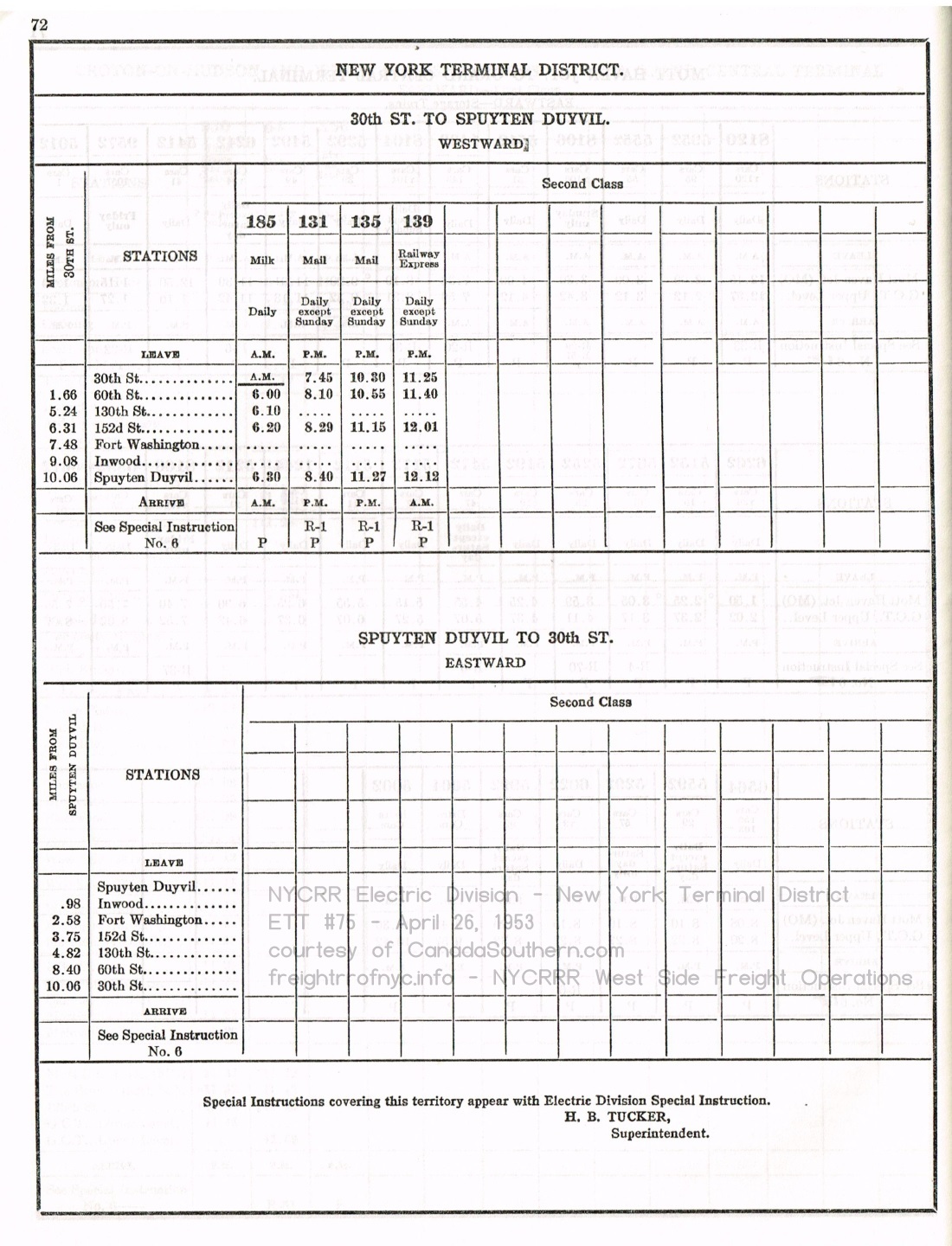

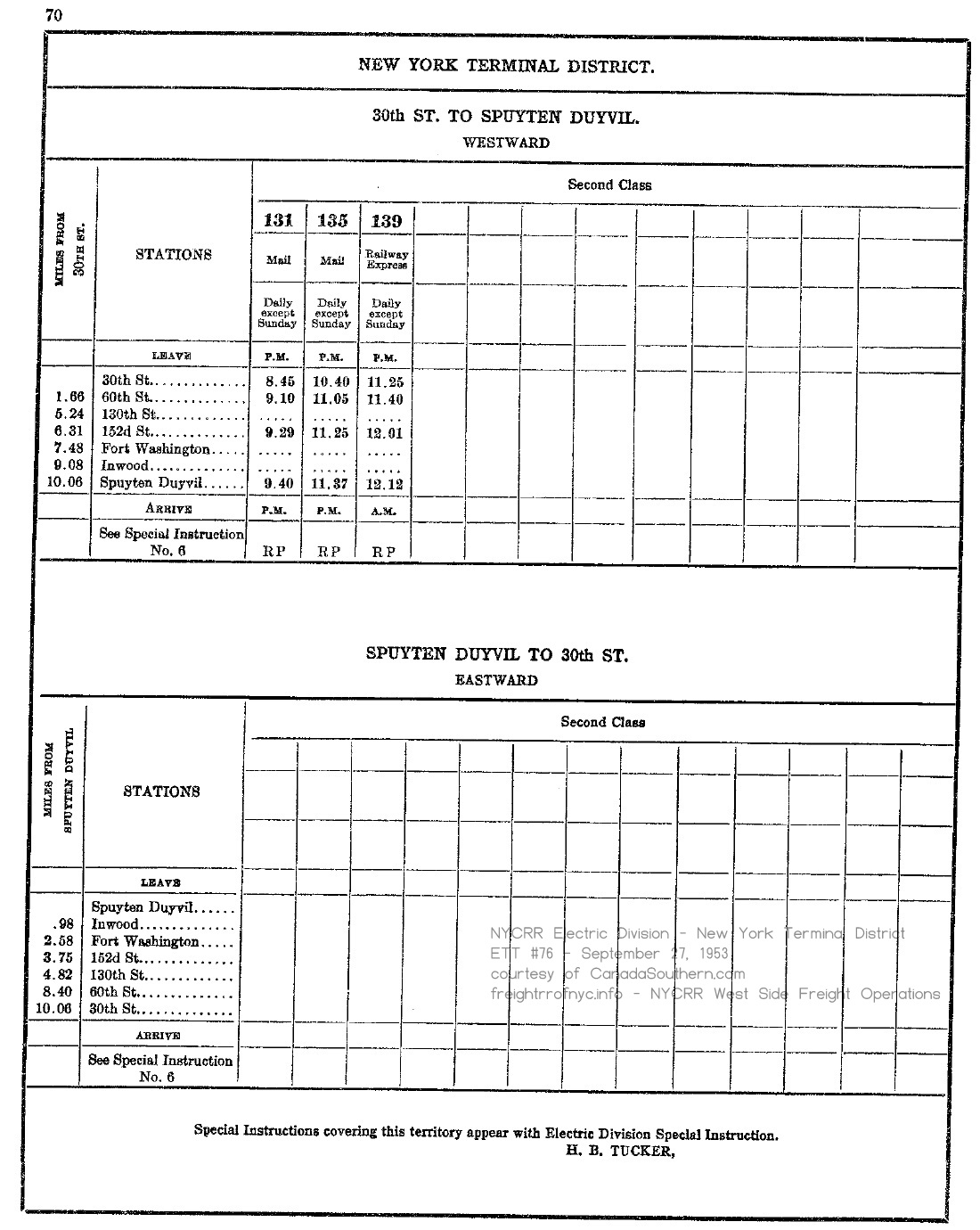

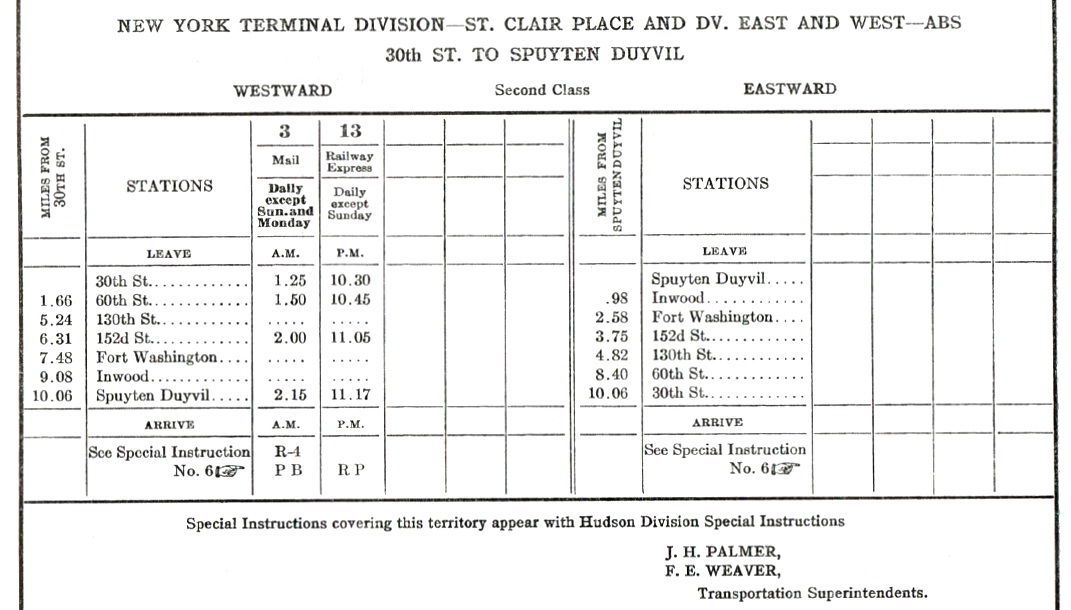

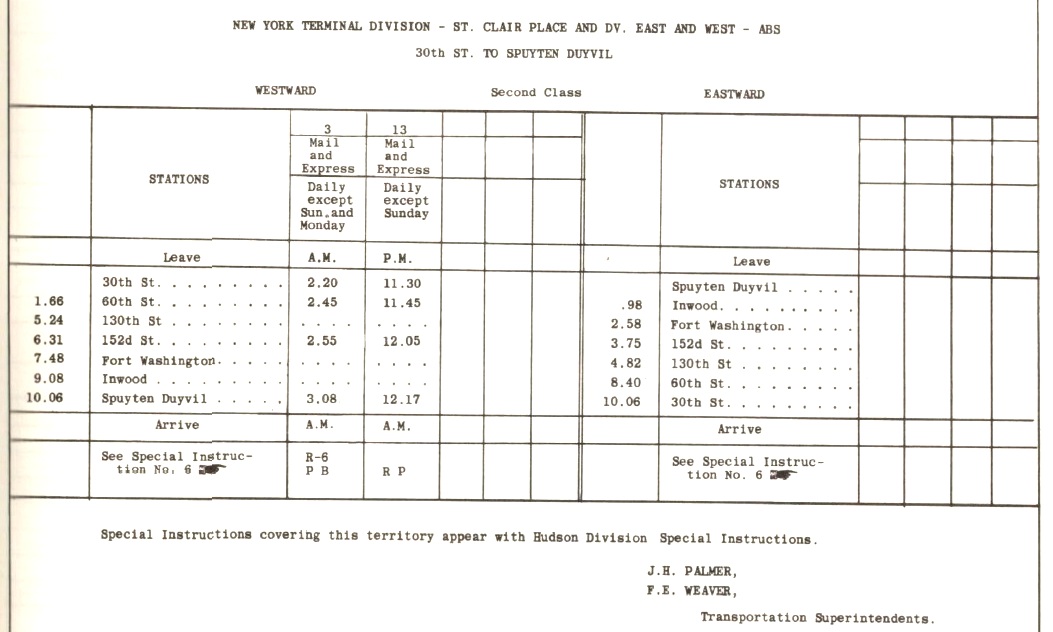

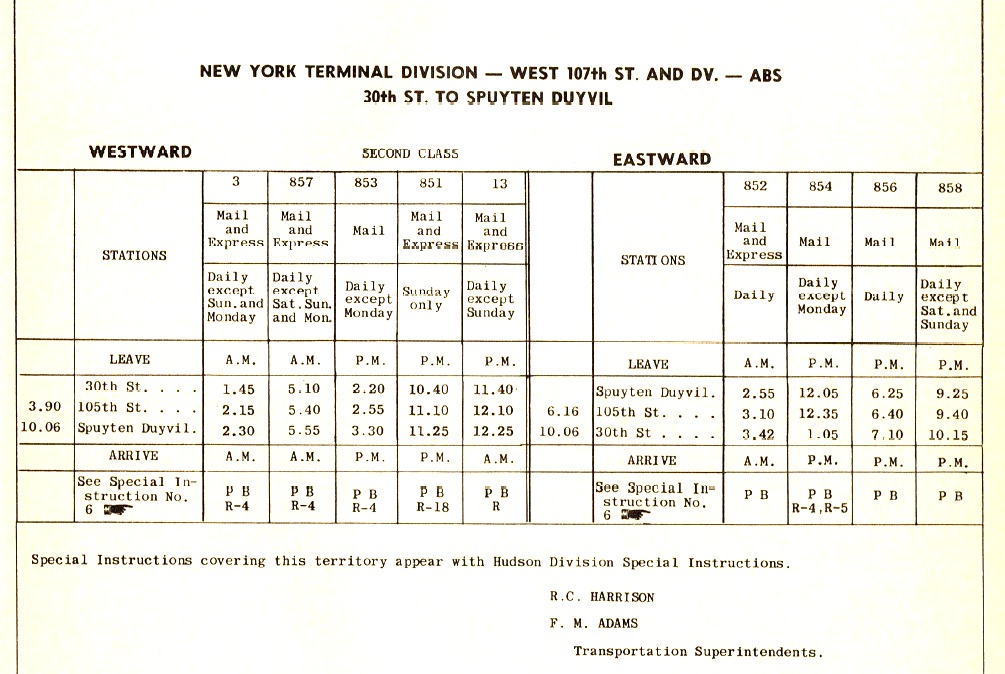

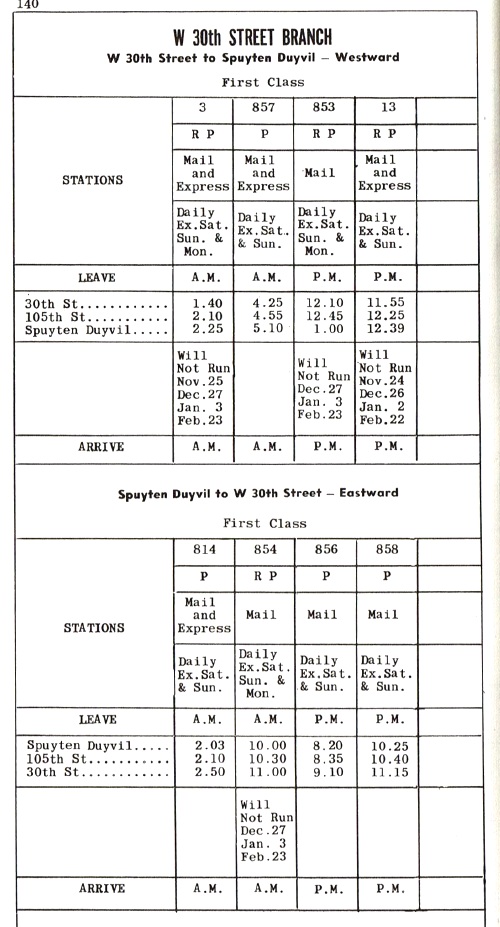

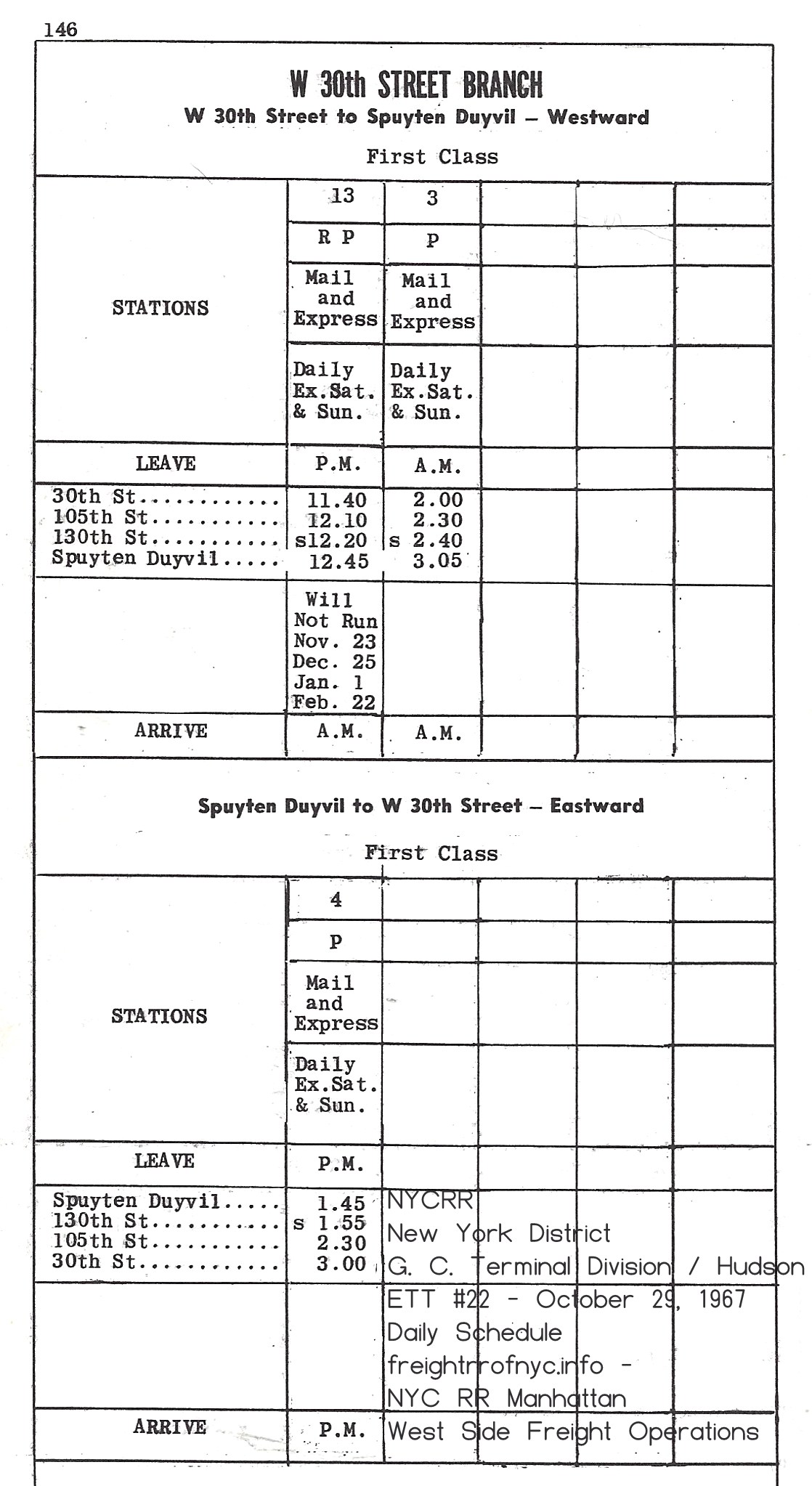

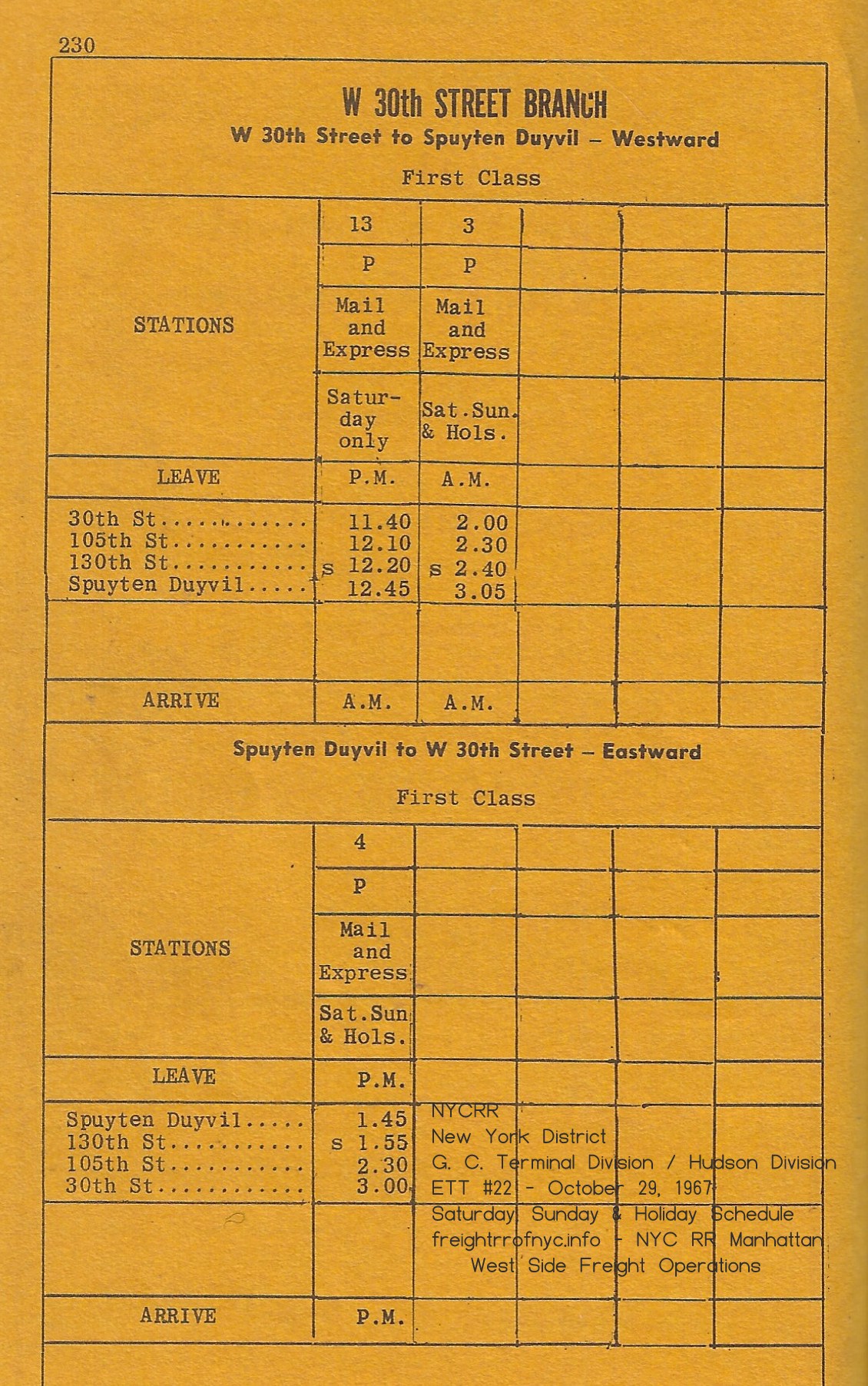

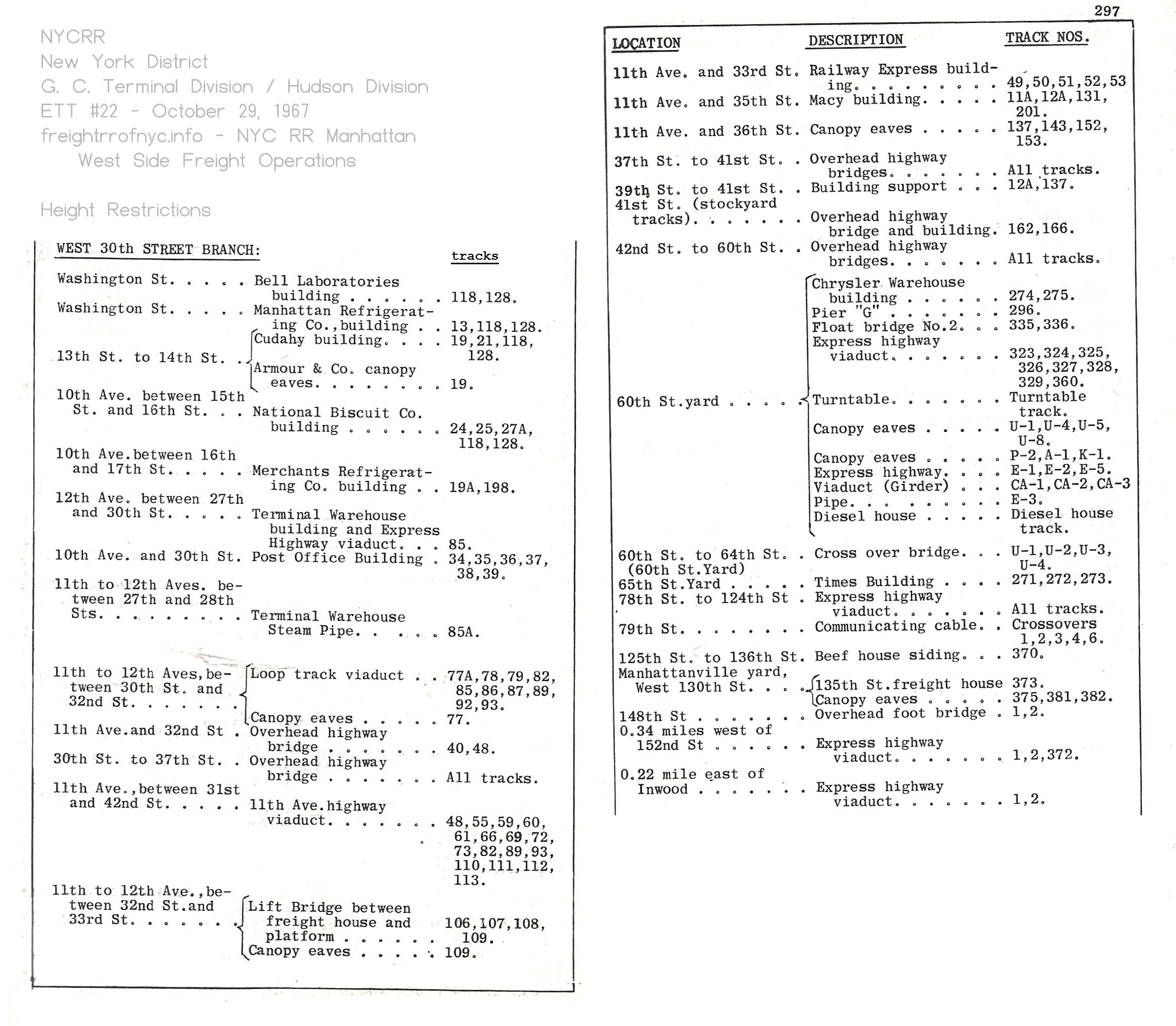

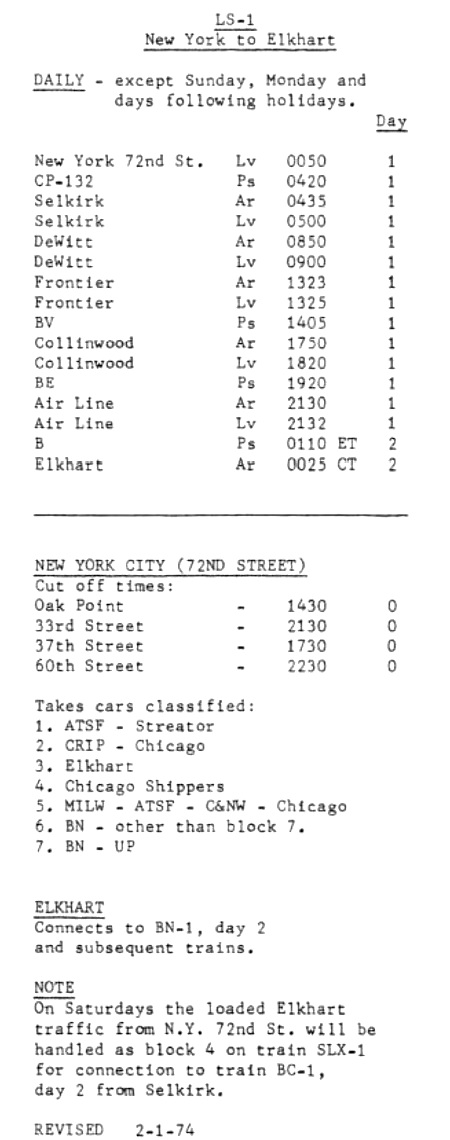

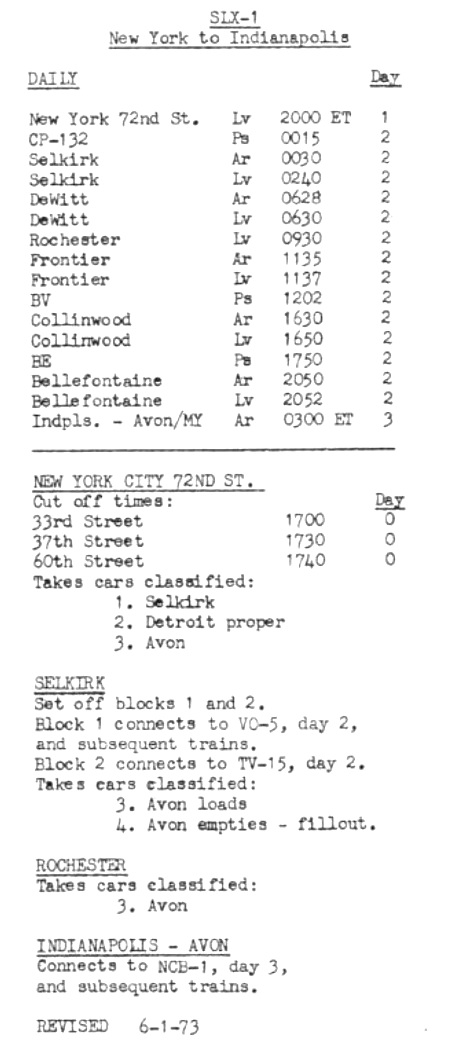

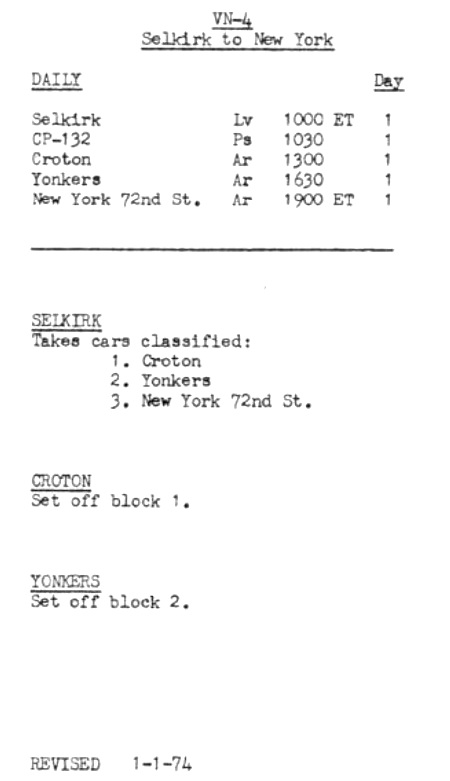

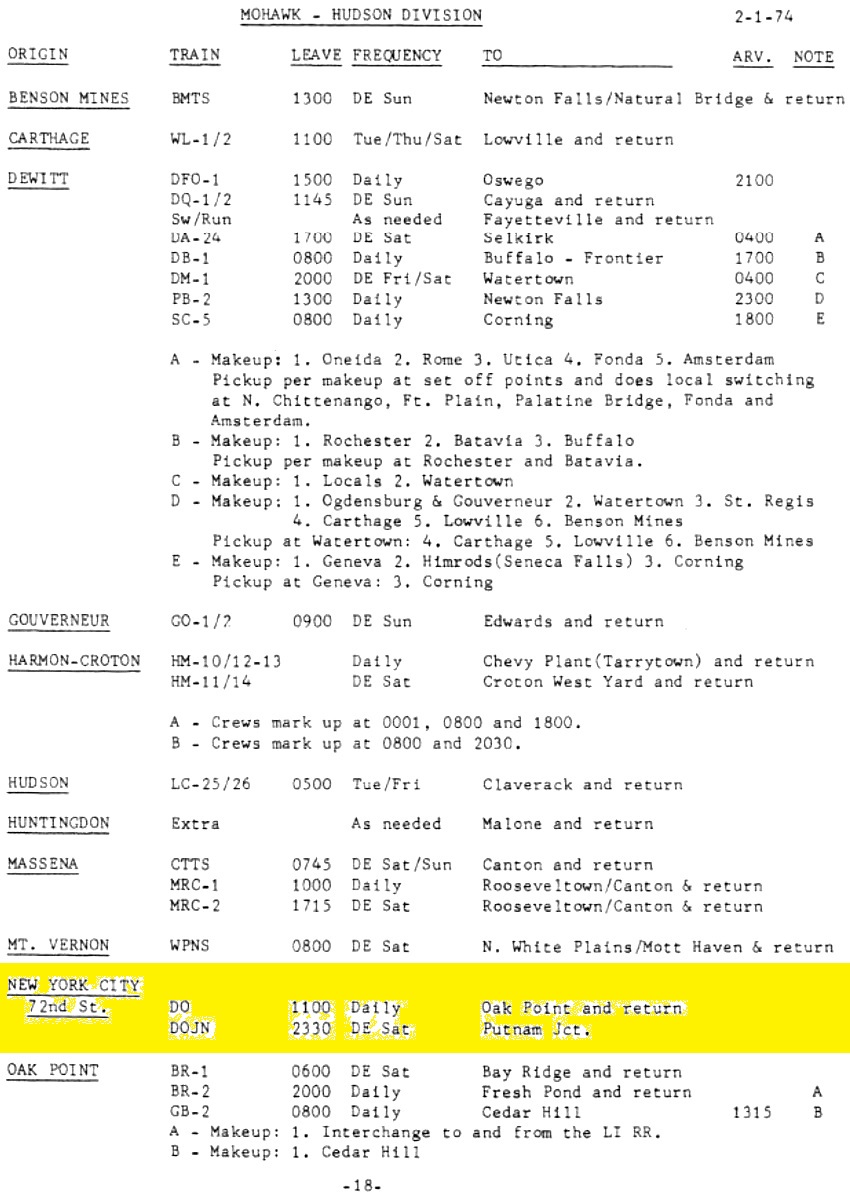

| NYC RR ETT #22 October 29, 1967 added | 9/2/2025 | Employee Time Tables & Train Symbols |

| 1955 Bromley Map of West 60-72nd Street Yards added | 9/2/2025 | Maps |

| DES-a, Q and R classes added to Locomotive page | 8/25/2025 | Page 2 - New York Central Manhattan Operations Locomotive Photos & Roster |

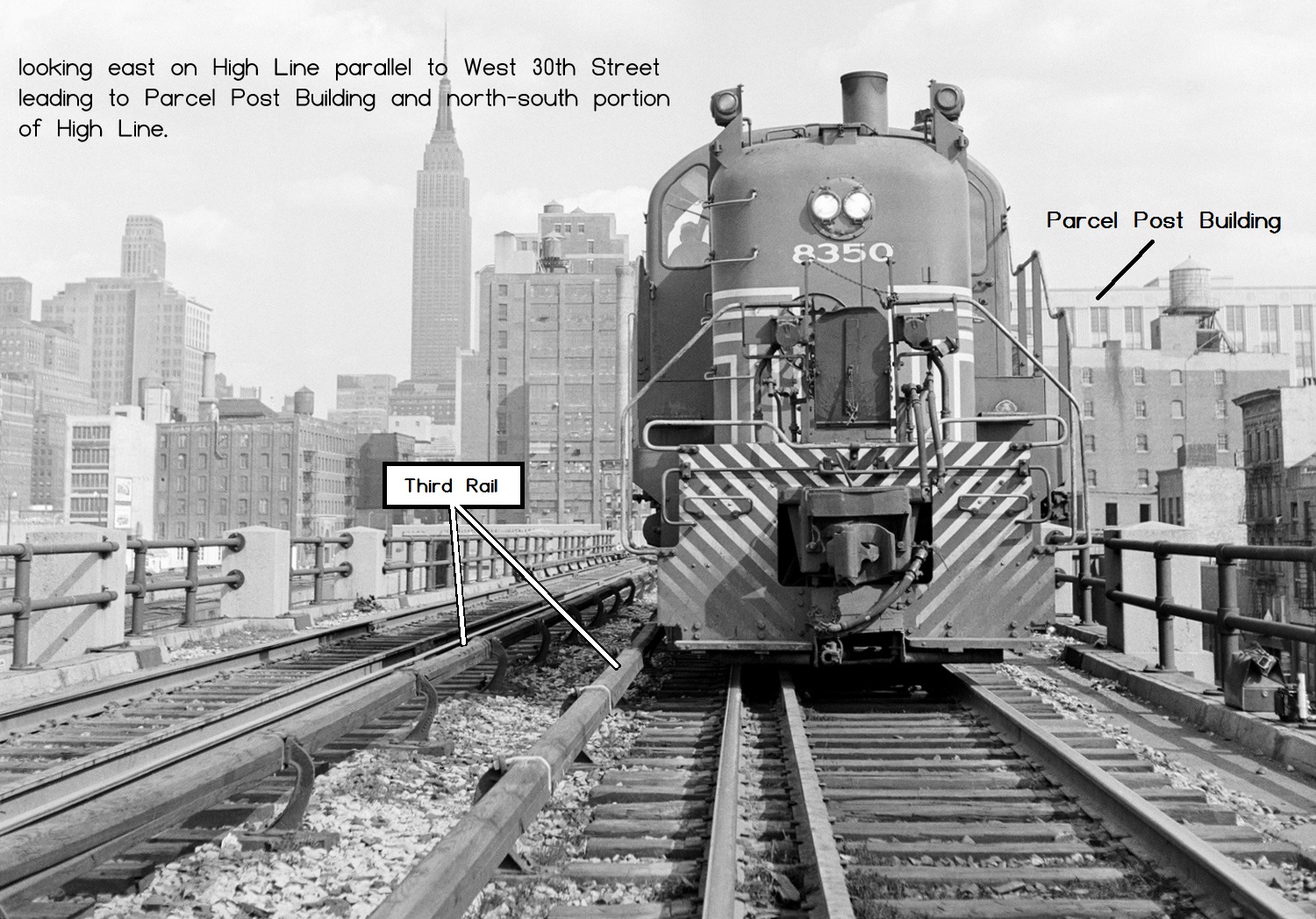

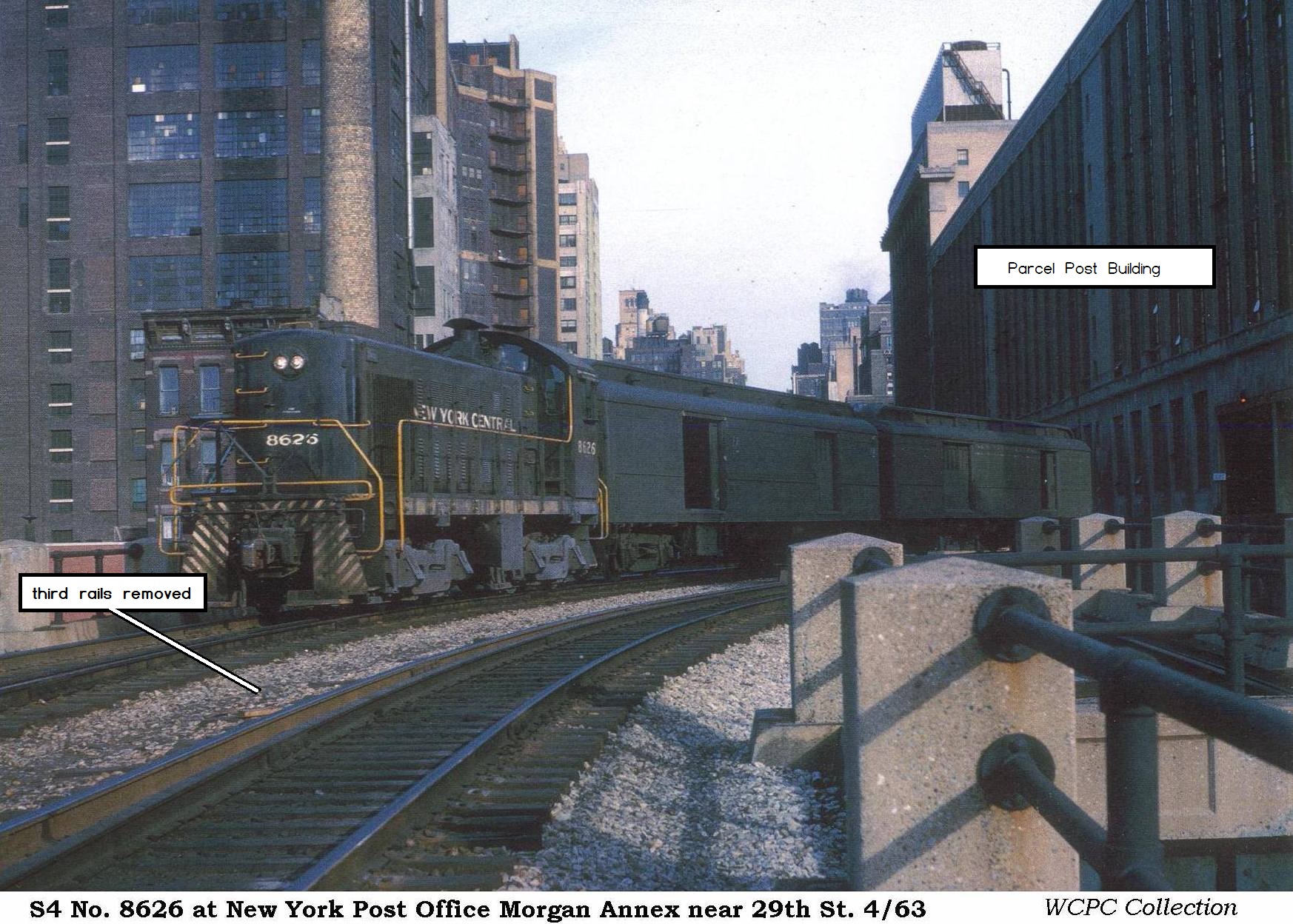

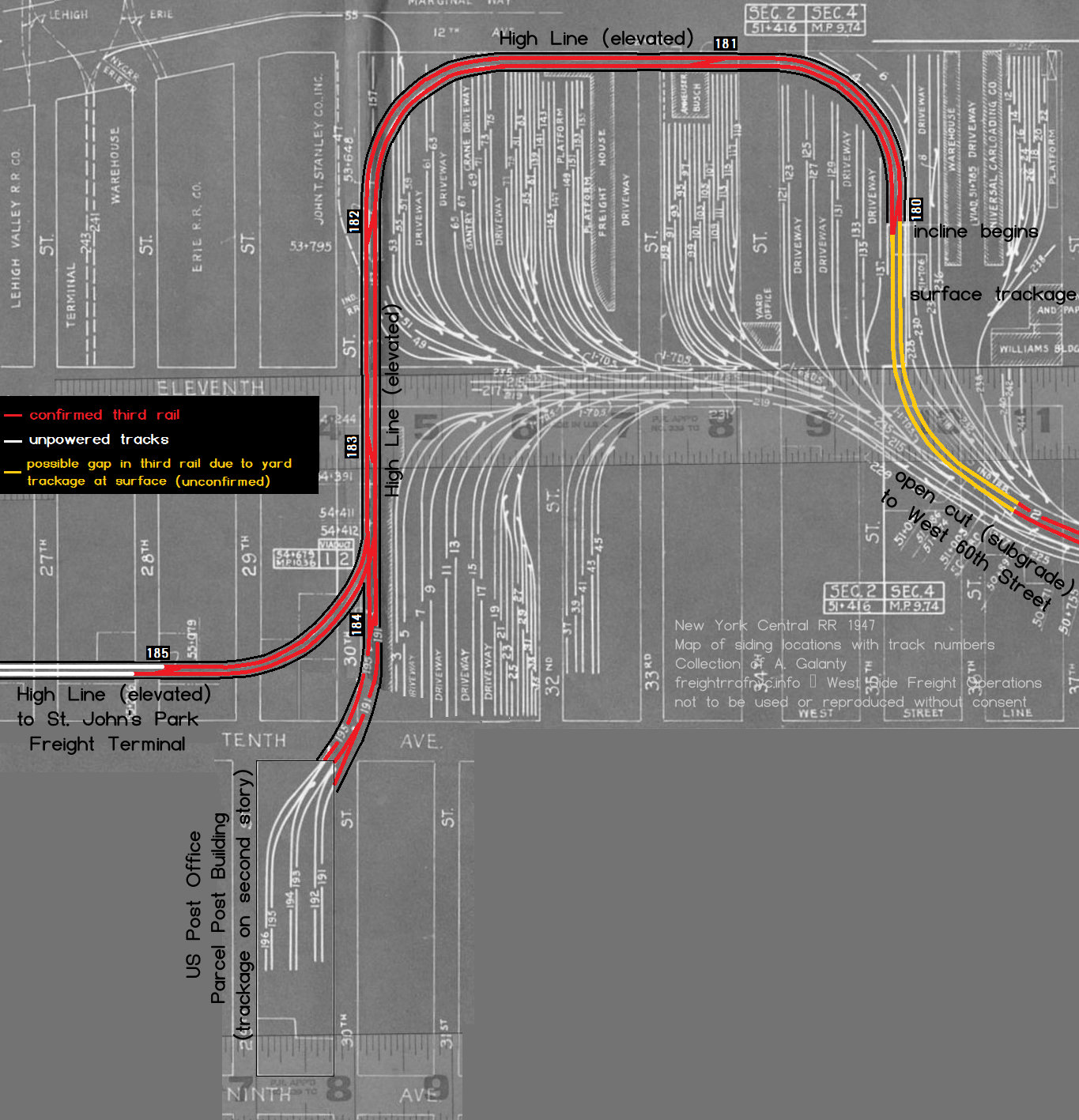

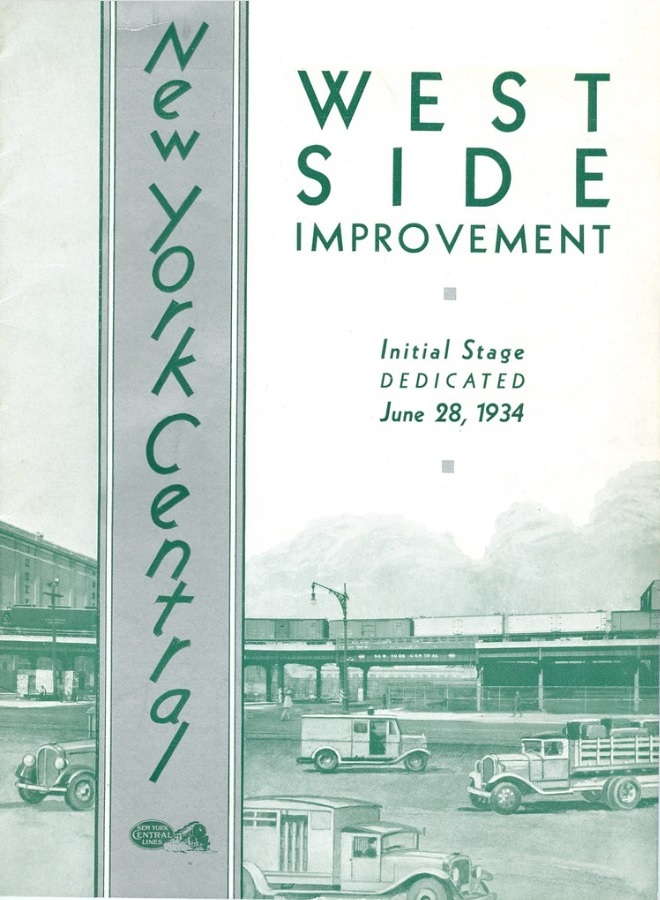

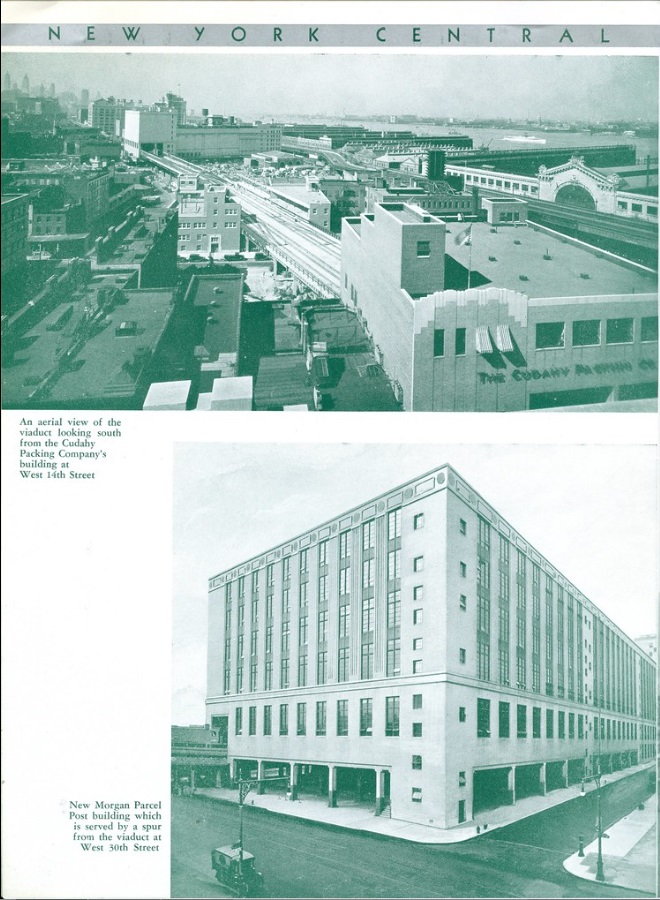

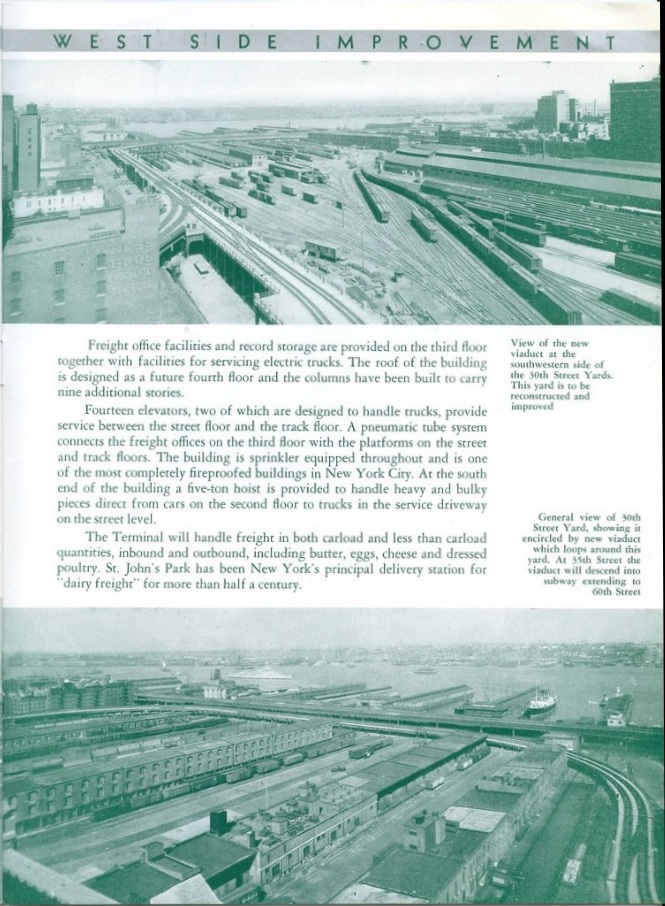

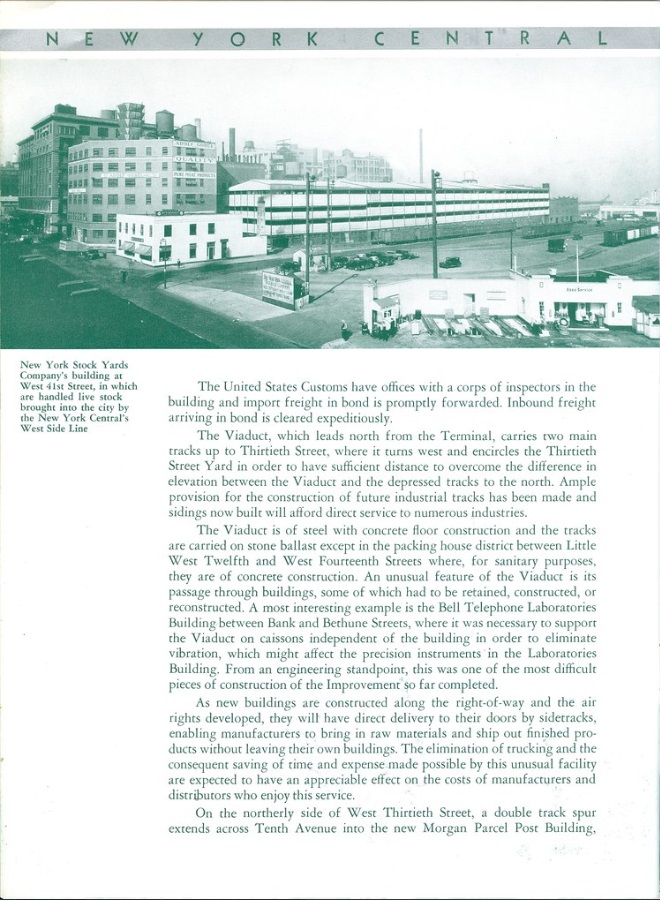

| West Side Improvement Booklet issued by New York Central - 1934 | 8/24/2025 | West Side Improvement Booklet issued by New York Central - 1934 |

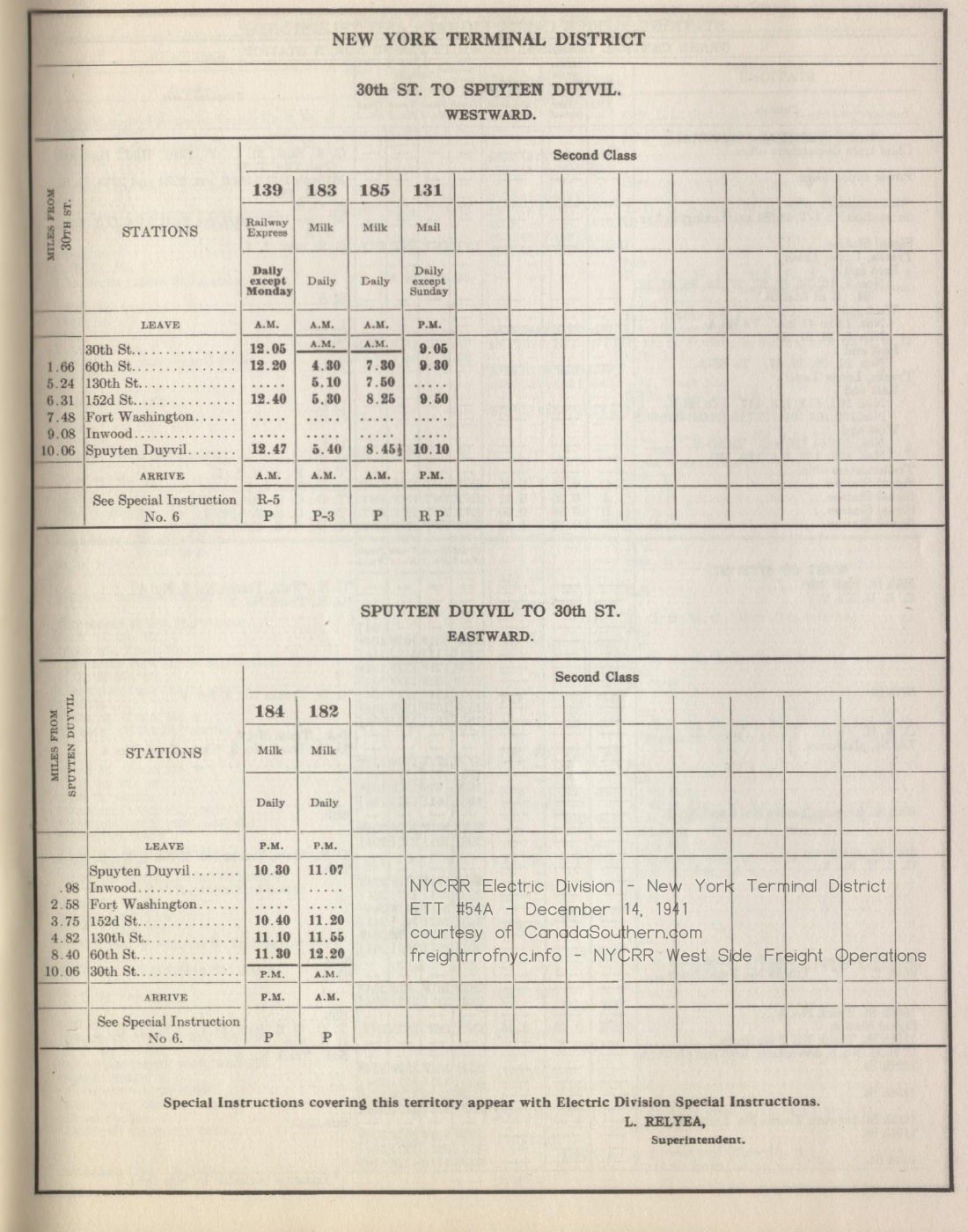

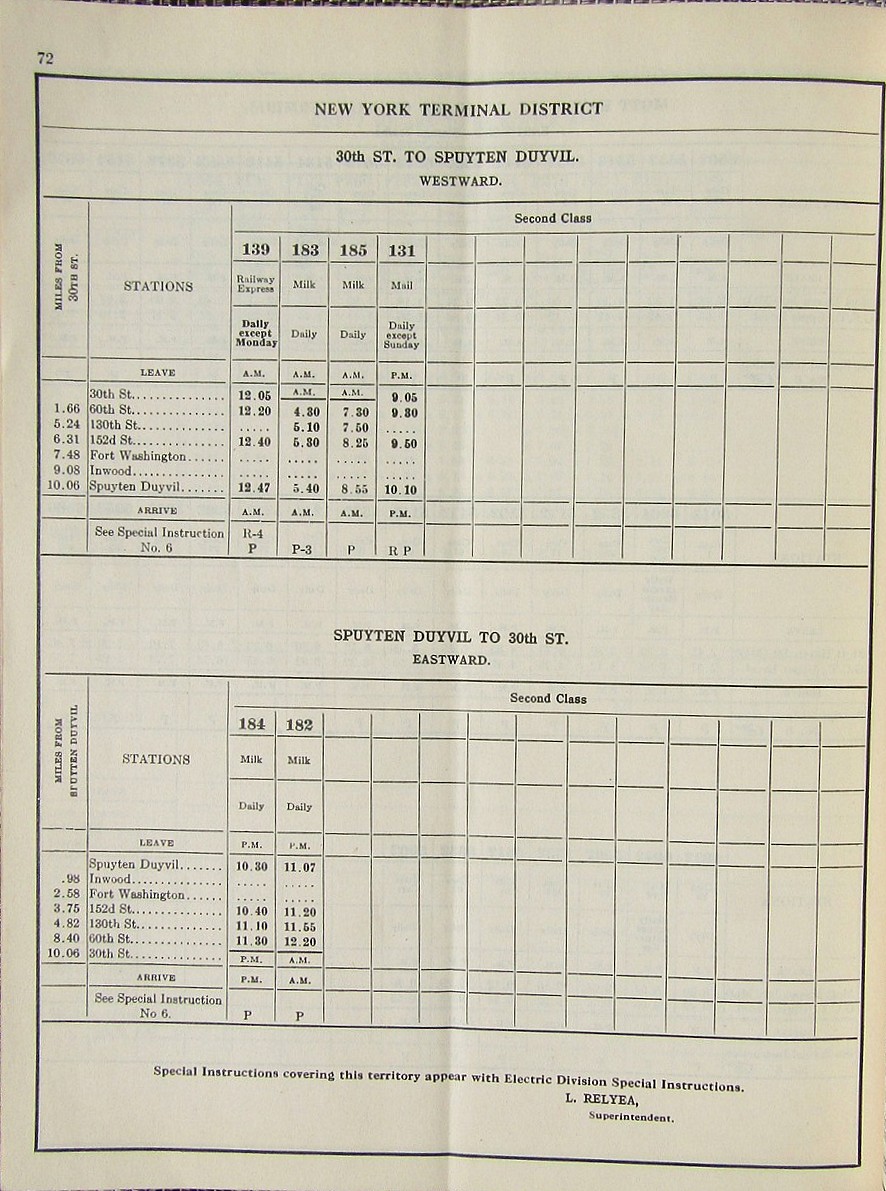

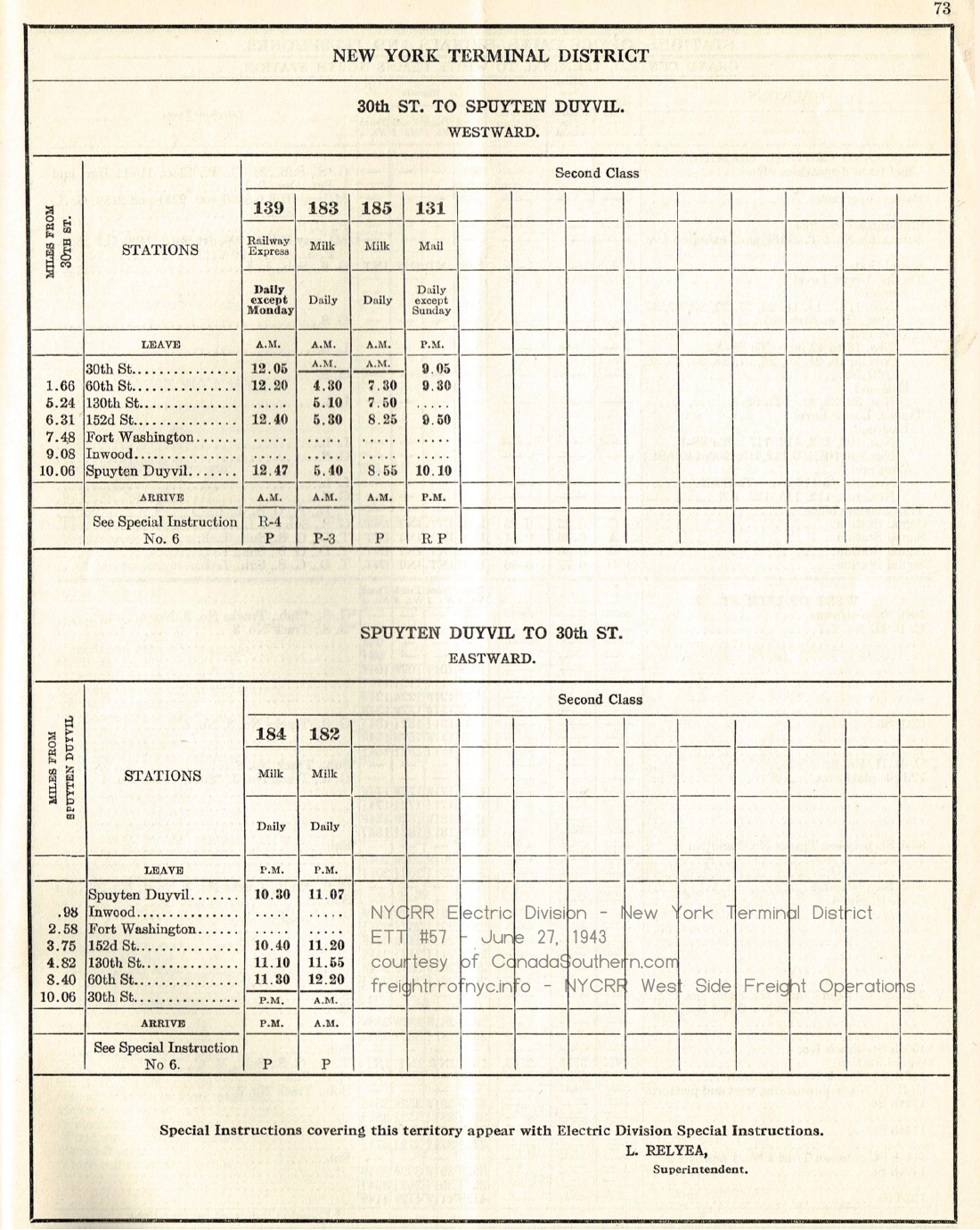

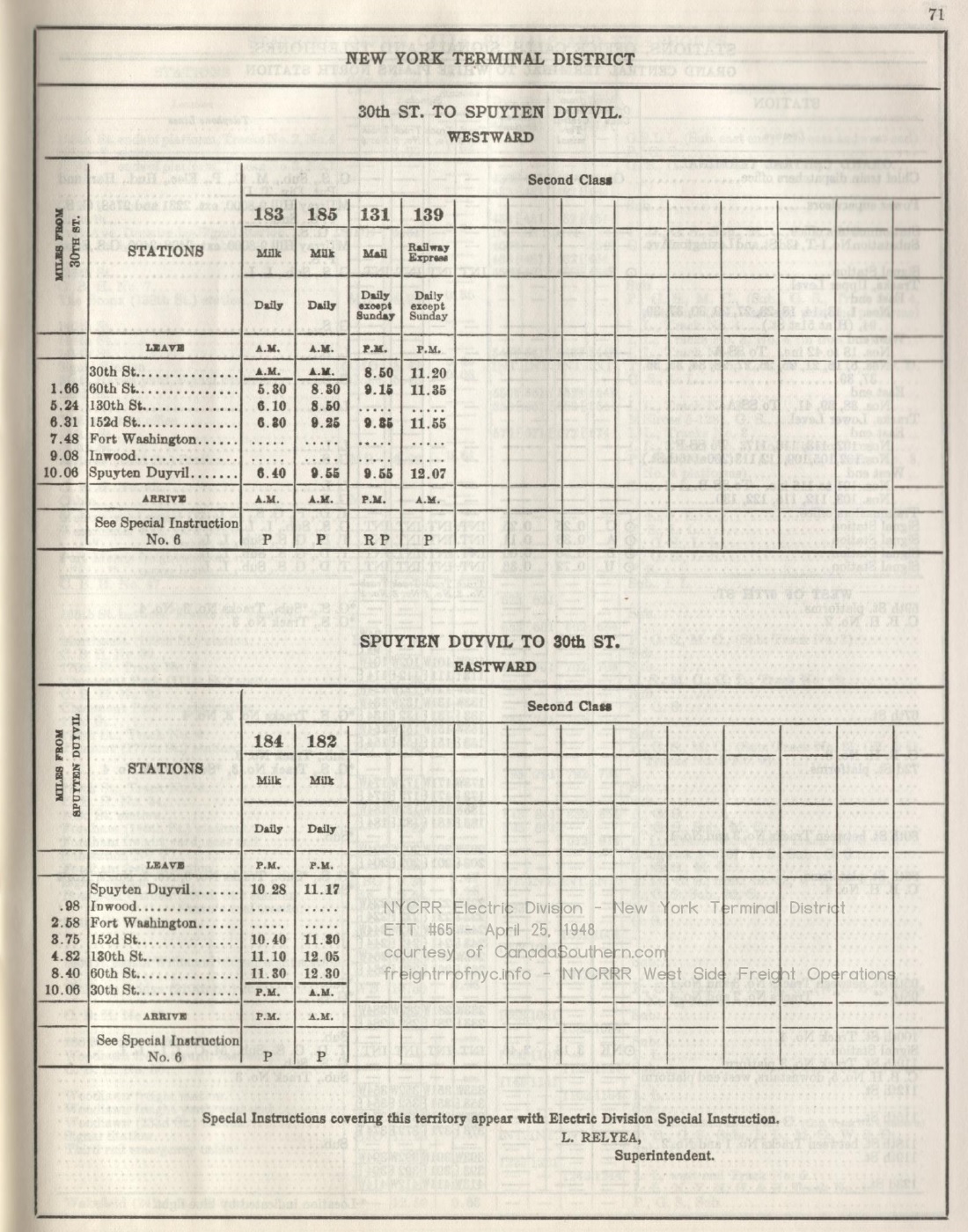

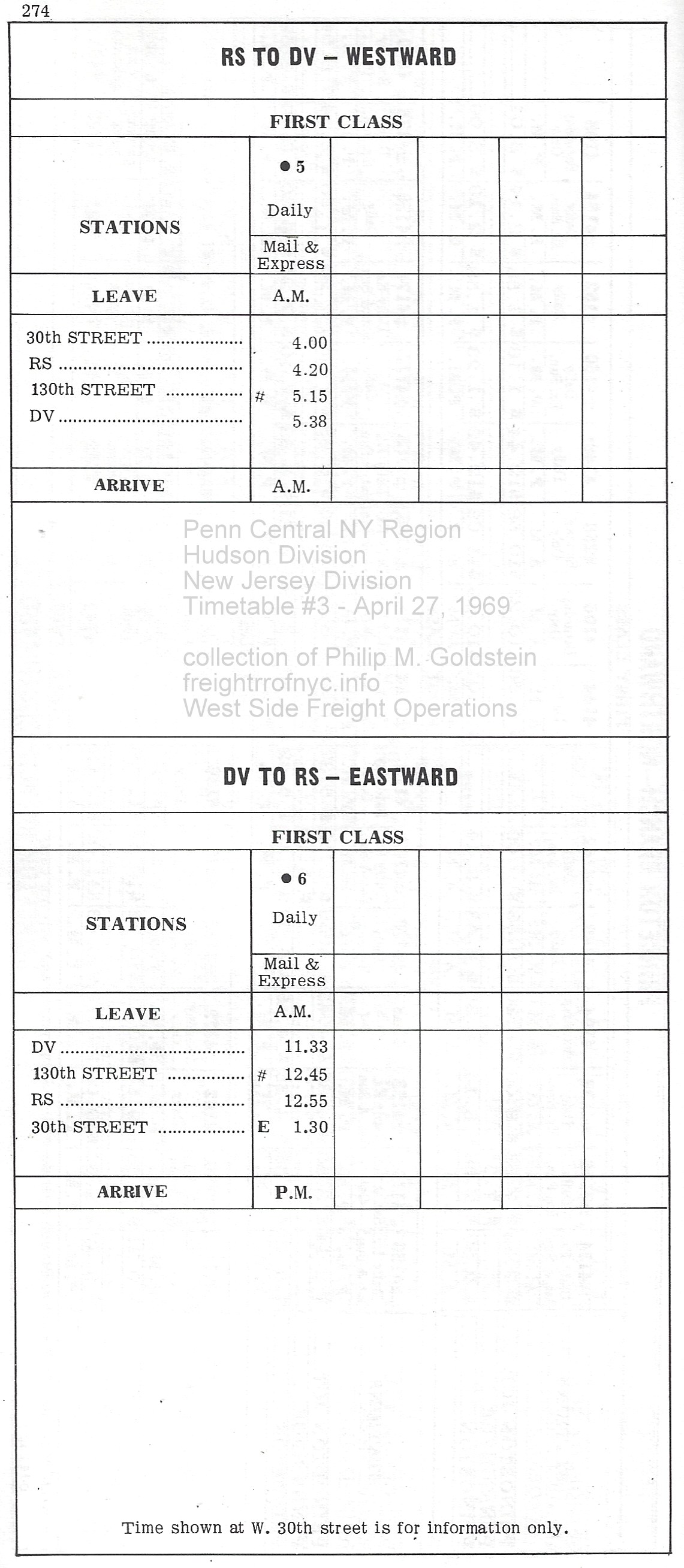

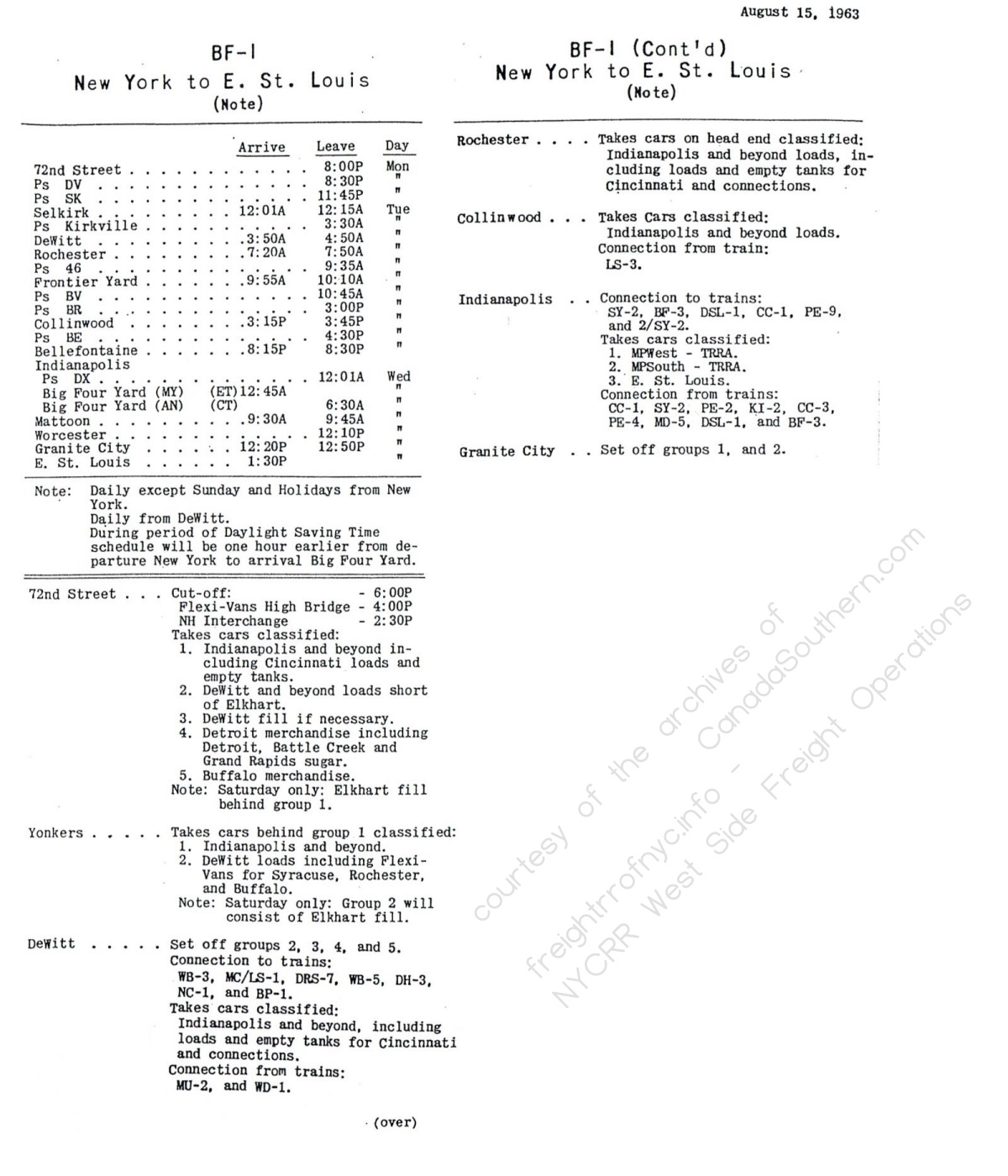

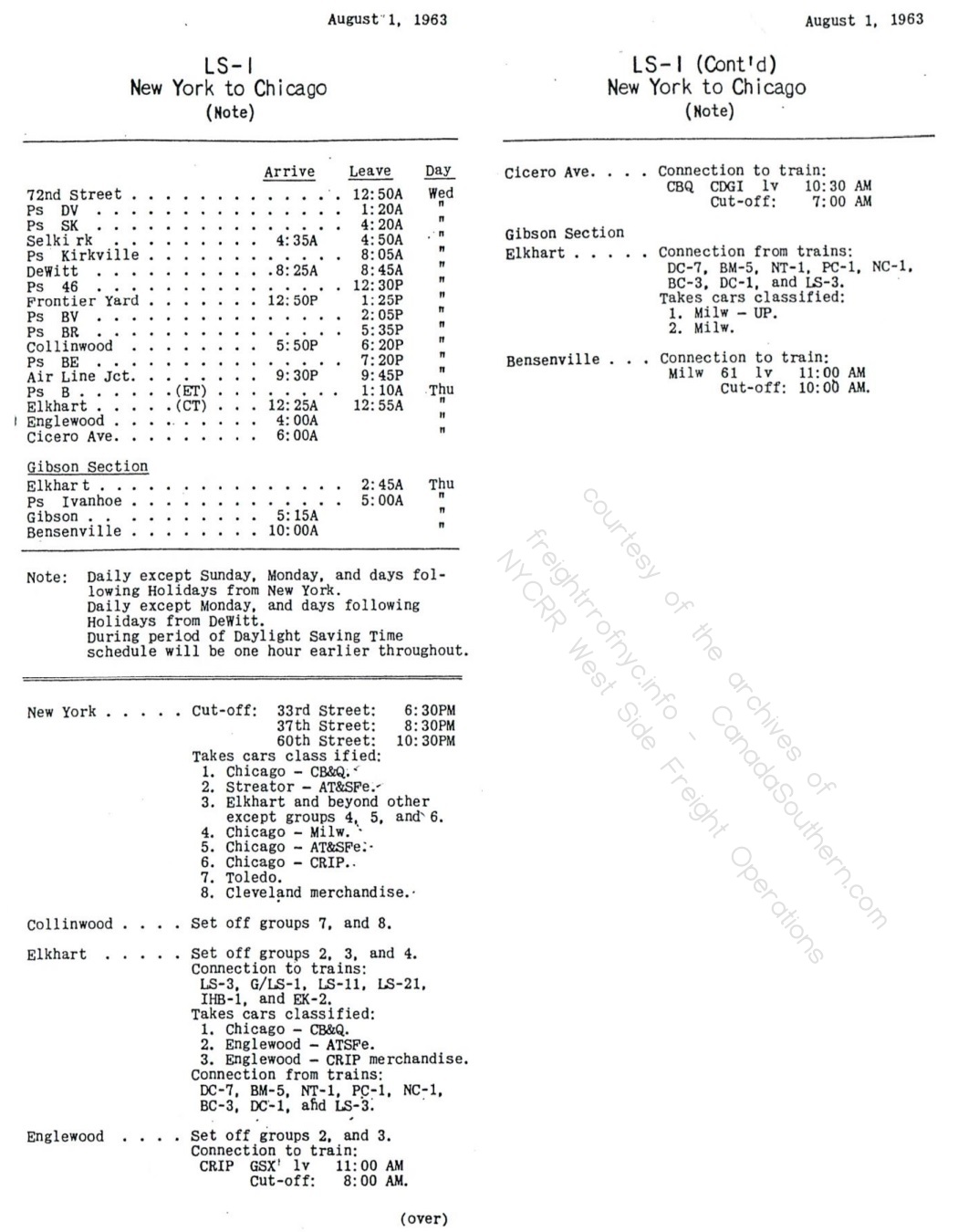

| Third Rail chapter added, Freight Schedules and Symbols added |

8/23/2025 | Third Rail Employee Time Tables & Train Symbols |

| Chapter added - Conrail's Last Move on the 30th Street Branch | 8/21/2025 | 1982 - Last move on the 30th Street Branch - Conrail |

| Locomotive images & rosters moved to own page | 8/20/2025 | Page 2 - New York Central Manhattan Operations Locomotive Photos & Roster |

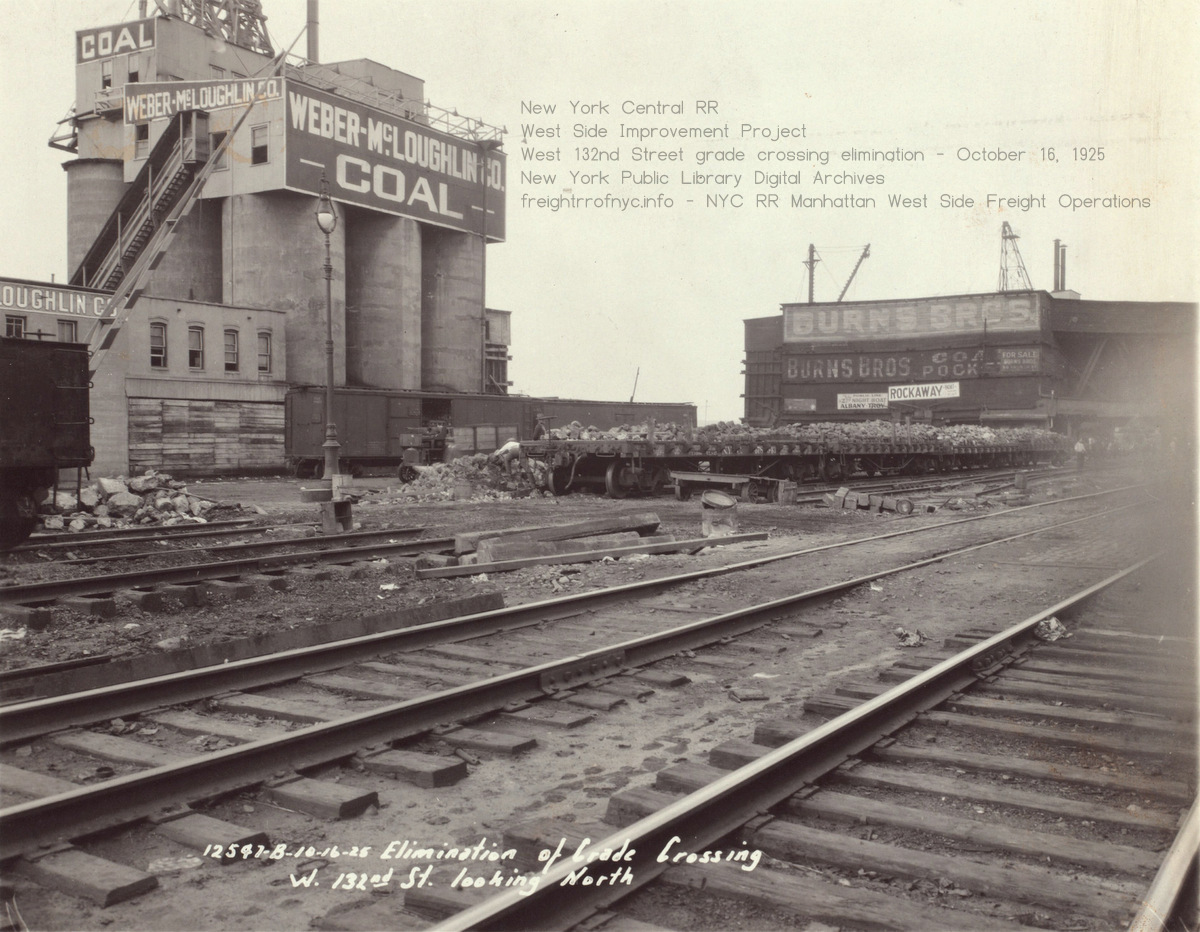

| NYPL Digital Archives P. L. Sperr images added to all chapters | 8/19/2025 | |

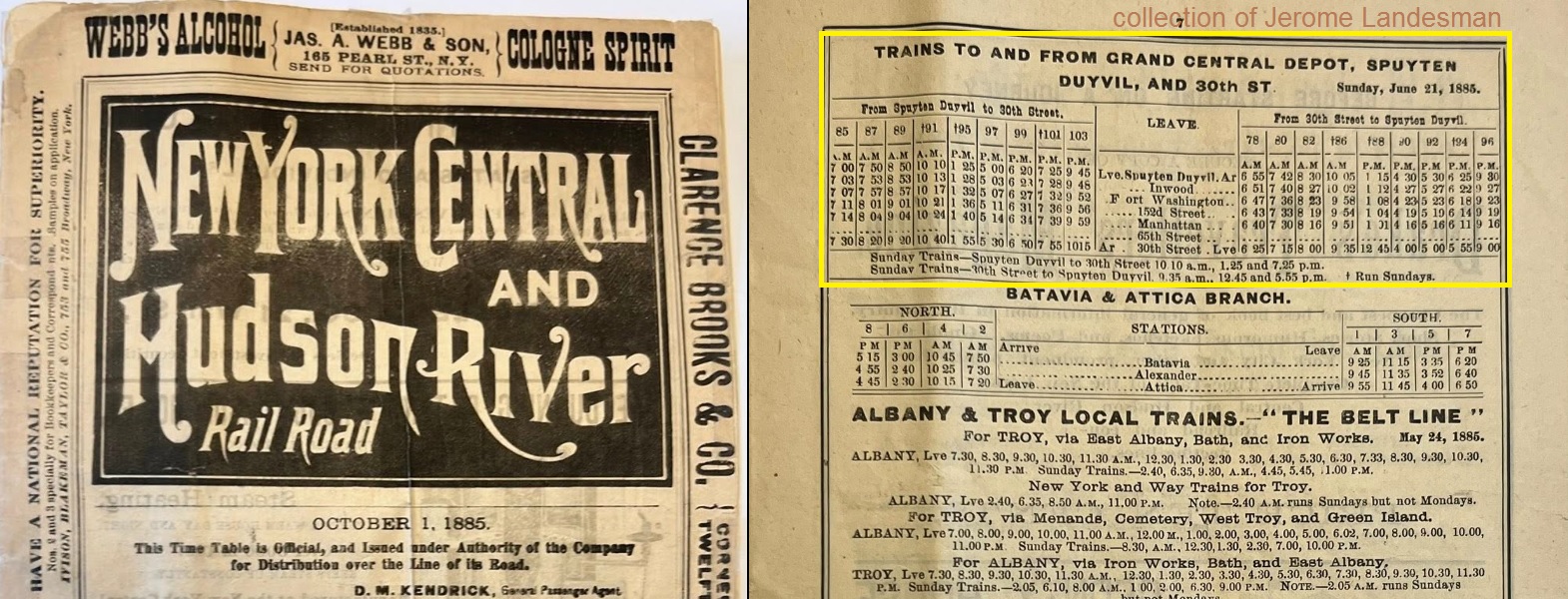

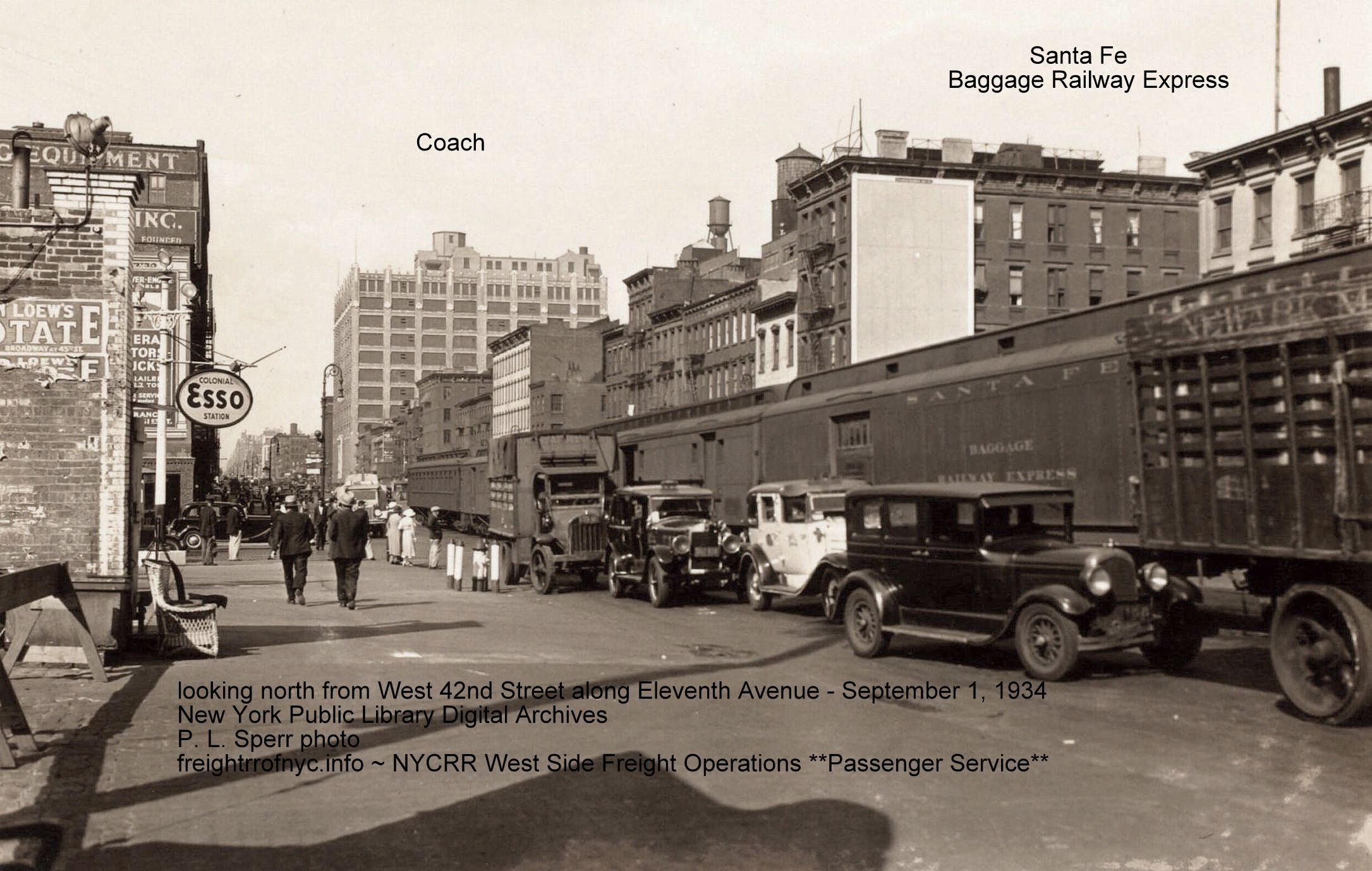

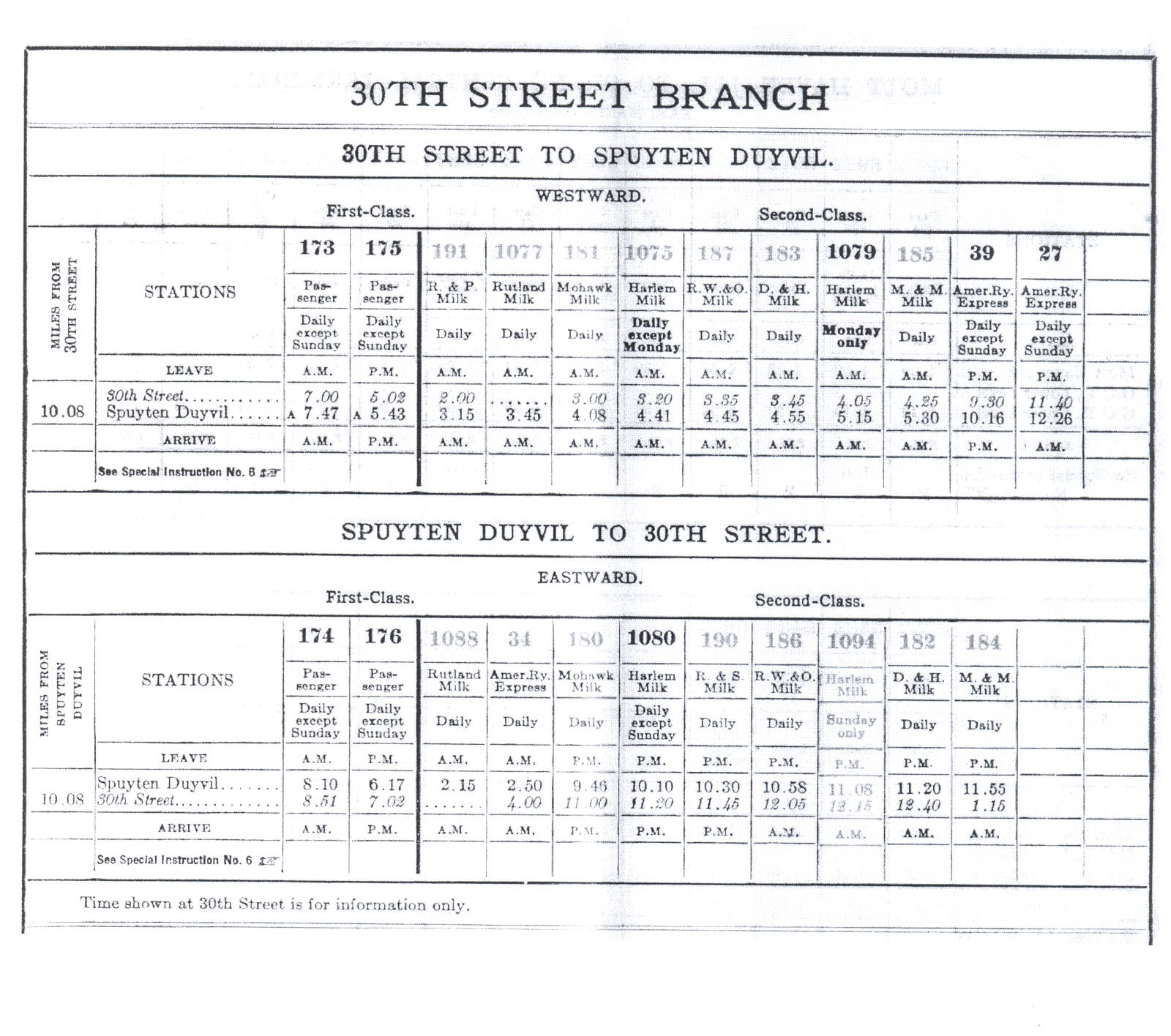

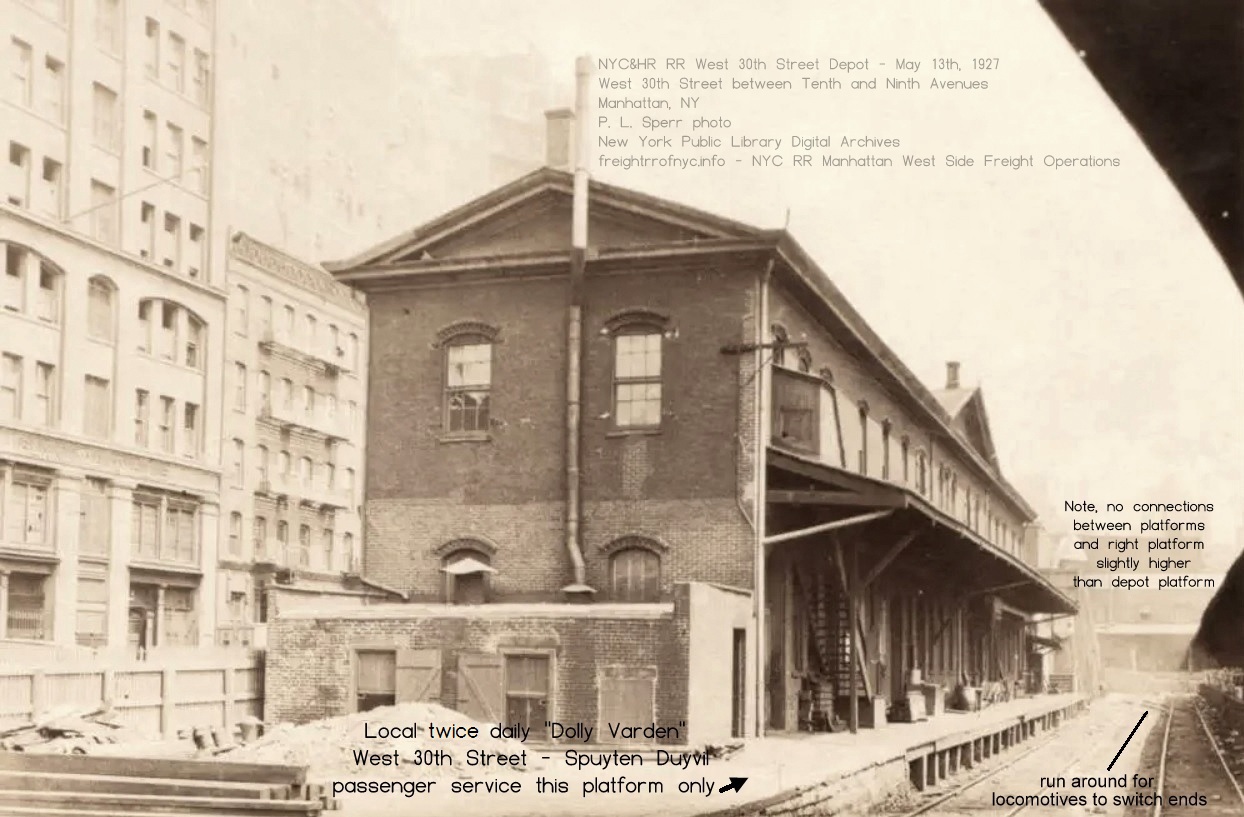

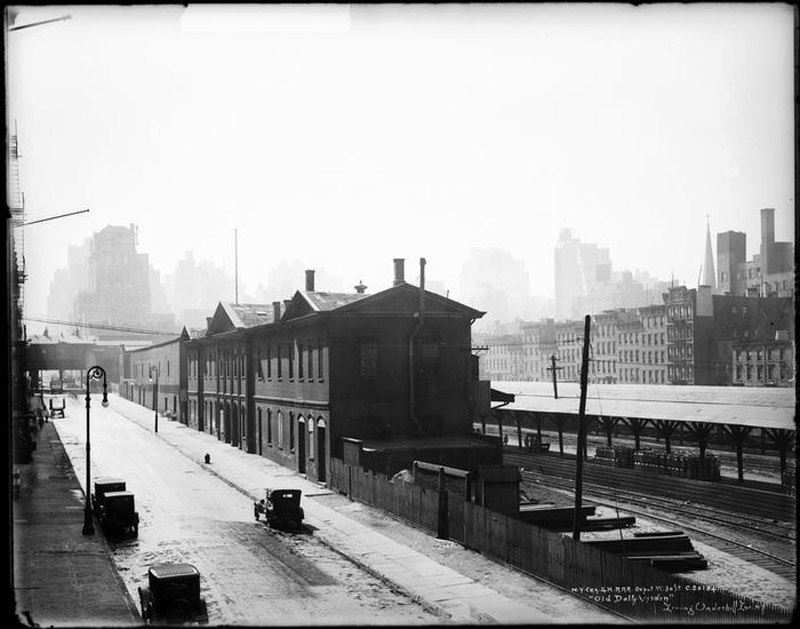

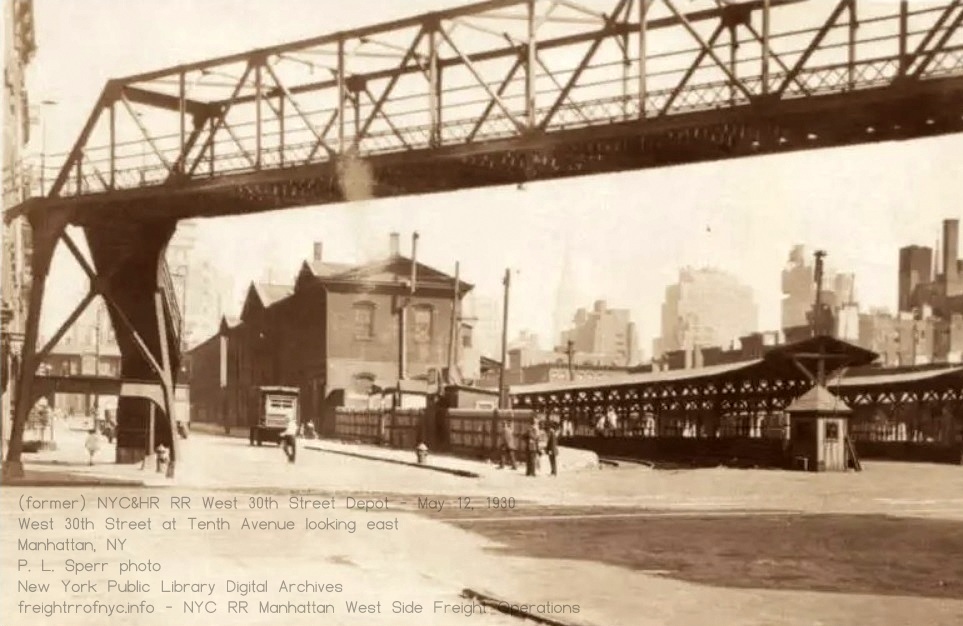

| Passenger Service chapter added, maps added & reorganized, ETT's added | 8/16/2025 | Passenger Service!?!? |

| New York Municipal Archives images added to several chapters | 8/14/2025 | |

| page added 01 April 2024 - basic contents formerly known as Misc Freight RR Images page | ||

.

.

New York Central & Hudson

River / New York Central Railroad

Street & High Line Operations

West Side - Manhattan, NY

.

.

.

"Revisionist history is the re-interpretation of established historical narratives, often challenging orthodox views by introducing new evidence or different perspectives to correct misconceptions or highlight overlooked aspects. While it can be a legitimate scholarly practice to provide a more nuanced understanding of the past, the term can also be used negatively to describe the deliberate distortion of historical facts for political or social agendas.".

Philip M. Goldstein

The Hudson River Railroad comes to Manhattan

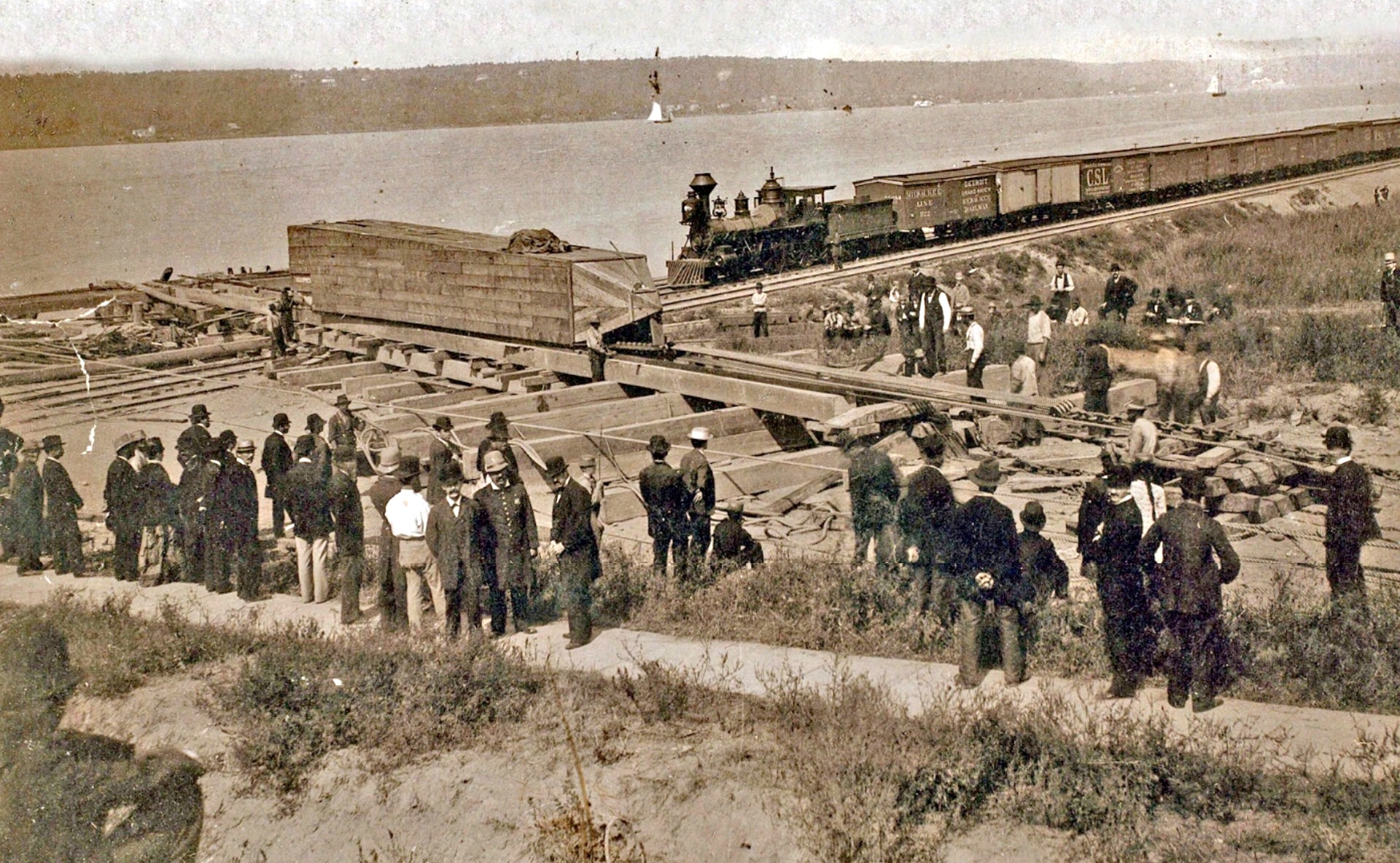

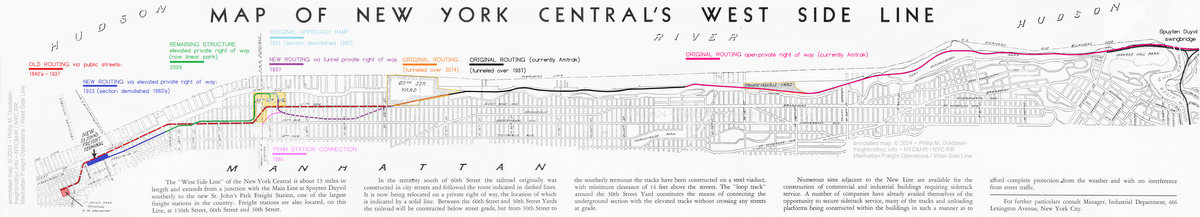

Freight operations on the West Side in Manhattan began with the Hudson River Railroad, which was owned by Erastus Corning. The Hudson River Railroad was granted a charter from the city of New York to operate freight and passenger trains south to Chambers Street.

The following is quoted directly from the 1920 Joint Report with Recommendations:

As originally laid out, the trains were brought as far south to a station located on the corner of Chambers Street and College Place / West Broadway beginning on October 8,1851.

Backing up in history just a tad,

Cornelius Vanderbilt obtained control of the Hudson River

Railroad in 1867. This direct route via the Spuyten Duyvil swingbridge gave the New York Central access to the "Water Level Route" which ran north along the Hudson River to Rensselaer, NY; where it could go east to Boston, Massachusetts or cross the Hudson River into Albany and go west to Chicago, Illinois; and through connections even farther to the West Coast; north to Canada; or back south to New Jersey and other points south along the Eastern Seaboard.

Unlike the other Class 1 railroads that did come to have offline freight terminals in Manhattan, such as the Pennsylvania; Lehigh Valley; Erie; Central Railroad of New Jersey; and the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroads; the New York Central Railroad had an unbroken direct rail connection to and from Manhattan to the mainland United States rail network. Ironically, this physical connection still exists to this very day, albeit slightly rerouted to get the trains off the streets (which we will address in a later chapter on this page), and is now under Amtrak usage for passenger service.

In 1881, the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railroad

had been planned as one link in a chain of

a new transcontinental railroad

from New York to San Francisco. This chain was to be comprised of the

West Shore; the New York, Chicago and

St. Louis Railroad or "Nickel Plate Road"; the Chicago,

Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway, the Northern Pacific Railroad; and the

Oregon

Navigation Company.

This

interview was then published in the Chicago Daily News, but

Vanderbilt's words and the context were modified, with particularly

heavy emphasis on "The public be damned." Several different

accounts of the incident were then disseminated; the accounts vary in

terms of who conducted the interview, under what circumstance and what

was actually said.

The stock prices of the two railroads rose

immediately and naturally, the principals and the shareholders were pleased.

. Why was the Hudson River Railroad permitted to operate locomotives in the streets and not the New York & Harlem? While this is a question that needs a firm answer, I suspect that answer may be read between the lines of the Joint Report with Comprehensive Plan and Recommendations of 1920: New York, New Jersey Port and Harbor Development Commission: The line handled passenger as well as freight business, inasmuch as the Park Avenue line to what is now Grand Central Station belonged to an entirely different company, the New York & Harlem Railroad Company.

And

so it appears, while the Hudson River Railroad engaged in both freight and

passenger service, freight was its bread and butter (figuratively and

literally!) Otherwise, why would it give up its passenger depot at

Chambers and build an exclusive freight terminal?

It is imperative to keep in mind at this point in time; the New York & Harlem River Railroad, was still a competitor to the Hudson River RR. It would not be until Cornelius Vanderbilt purchased both, that he brought them under the same umbrella a few years after in 1869.

. |

||||||||||||

|

. .

One of my pet peeves, is that I particularly despise the moniker "Death Avenue" - of which Eleventh Avenue (and Tenth Avenue) became to be called as a result. This "Death Avenue" moniker is a bit of hyperbole and quite sensationalist. Unfortunately, it has become so ingrained throughout the historical accountings of the West Side Operations, that referral to simply "Eleventh Avenue" or "Tenth Avenue" does not carry the same effect. The 1800's and early 1900's - and with them the coming of the Industrial Age - were an inherently dangerous period of time in itself. People were maimed and killed by lots of things in daily life; pedestrians were also run over by horsedrawn wagons on a daily basis or trampled by horses. Riders were thrown. Industry was drastically dangerous: coal mines, steel mills, lumber mills, steam boilers, bridge building, tunnel boring and land work with explosives, mechanized farm equipment, etc. Everyday life then was more of a hazard. In short, injuries and fatalities came from all sorts of machinery and industrial accidents, and not just this particular train or its routing. A "big deal" has been made about the 540 people were known to have been fatally injured by train movements through 1905 by the operations of street running freight trains in Manhattan. But you see, trolley cars caused deaths on the streets as well. These trolleys, so essential to the movement of people to and from work and school; were no different in the hazard they presented. They ran people over too. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle ran a full page feature page on December 30, 1894 blasting the deaths of so many from trolleys. "Frightfully mangled". "Beheaded". "Legs cut off". But no one individual or any holder of city office ever enacted or tried to enact legislation, that forbade the use of trolleys or made them move to another street or part of the city. The trolleys were a public service, you see.

And when the automobile was developed, entered mass production and became available to the private owner; automobiles increasingly caused death on the streets as well. So many injuries and deaths were occurring as a result of automobiles, that the New York Daily News began a clock-like "Hands of Death." The latest one in 1923 showed 889 people killed by "the automobile". In 1931, deaths as a result from automobiles reached 1,448. Yet, only a few people and politicians actually advocated banning the automobile from streets. Speed limits, perhaps; but not an outright ban. If one does the math, more people died from the automobile in the first 30 years of the 1900's, than in all of the 80 years the freight trains operated on the West Side since 1851. But it was the "big, bad freight railroad" that bore the brunt of the blame, and was an easy target. And while people needed the trolleys to go to and from work and school, go about their daily lives and what have you; they were an essential public service. Most transit companies of the era were considered "locally" owned. The perception was (and remains) the freight trains weren't. At best, they might have been incorporated in the State of New York, but their corporate offices may have been out of state.And even though the New York Central Railroad's headquarters were located right in New York City by Grand Central Terminal; they, like the other railroads were perceived to be owned by a faceless corporation owned by the ultra-rich, living in mansions along Fifth Avenue; while most of the rest of the population were crammed into tenements. The railroads always have and always will bear unjust ire and blame by the public, even to this day: .

A significant portion of the public outrage comes from the transport of chemicals by rail. Sensationalist media fosters chemophobia.

. The computer or smart device you read this on, the products you purchase and consume, use various chemicals which are needed to make plastics; as well as acids, and heavy metals in its construction. Acids are used to etch metals for electrical contacts. Plastics are used in food sales and storage: meats are sold wrapped in plastic for hygienic and sanitary reasons. The list of hazardous chemicals transported by rail, and that by processing become inert and used in our daily lives, is endless. So in short; accidents, are the inevitable consequences of living in a modern, first world, technologically advanced urban society. An ongoing hullabaloo is made about "bomb trains" which refer to unit trains of ethanol. During the 1960's and 1970's the uproar was over pollutants made by burning gasoline. Ethanol, made from corn; was developed as an alternate and renewable fuel source either by itself or blended with gasoline to reduce those airborne pollutants. Ethanol is manufactured in the Midwest, where the corn is grown, and it needs to be transported to the oil refineries which are usually located on the West, Gulf and East Coasts where oil comes by ship. Yes, these trains sometimes derail and catch fire. So do trucks. But the alternative is the re-introduction of pollutants from the burning of gasoline. This bothers you? What are the options? Going back to living in a cave, hunting for your food daily with a stone or a spear? Hell, even archaeologists have even found primitive man injured by those hunting implements! Point being, injury and death goes hand in hand with living. The more advanced the civilization, the more hazards there are that come about as a result of those advancements. Returning to the 1800's; and in the case of the New York Central Railroad back in the 1800's; when that railroad was owned by a very outspoken ultra-millionaire, like it was by William H. Vanderbilt living in a mansion of Fifth Avenue; well, they made for an easy target by the media. The railroads were, and remain to this day; to be perceived as a big faceless uncaring corporations. Not much has changed, has it? Despite this, that is not to say solutions and remedies were not attempted back then. One of the solutions to the hazard of operating trains through the city streets, was to have a man on horseback escort the trains during transit on public thoroughfares. Which brings us to our next chapter. . . . .

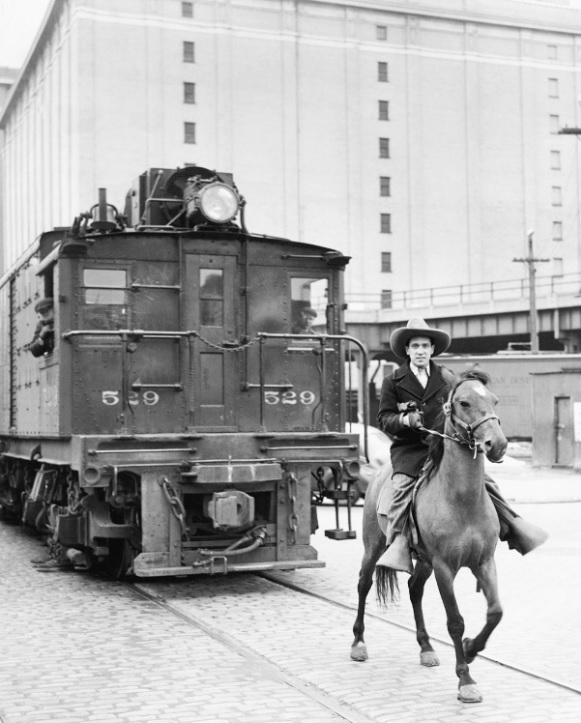

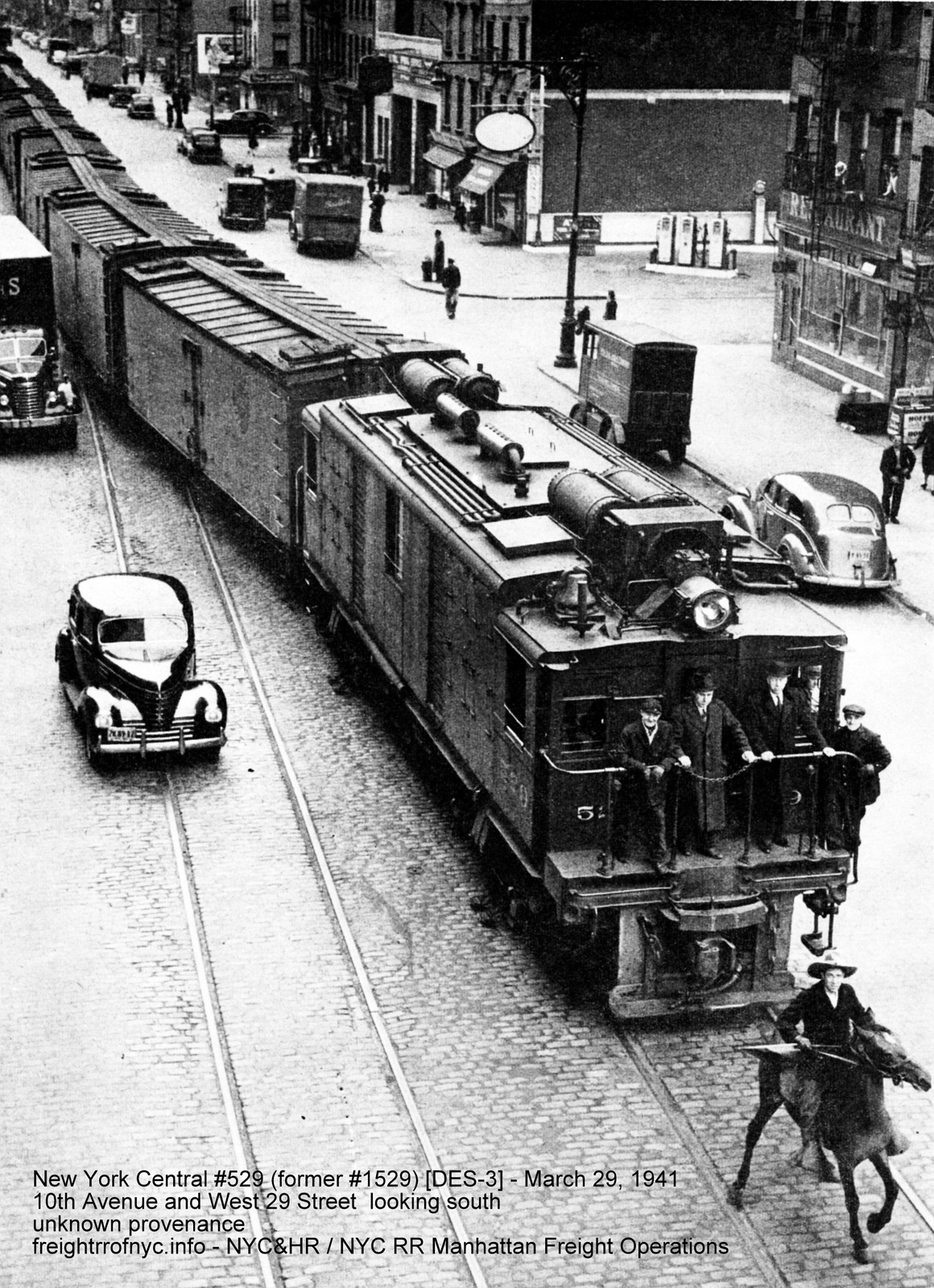

Mind you, this is just one paragraph of a multiple page agreement regarding the rights of the Hudson River Railroad to use streets and avenues in Manhattan to convey freight AND passenger trains to Chambers Street Depot. The unabridged text may be read by clicking on the excerpt of legislation above. It contains some very interesting information to say the least regarding which route the railroad had to follow, distances between cars, and other details lost over time. This horse rider was to lead the locomotive movement and warn pedestrians to yield to the oncoming train. An escort if you will. These horse riders became known as a "West Side Cowboy", or a "Dummy Boy" (after the steam dummy). They were also known as the Tenth Avenue (or Eleventh Avenue) Cowboy. And when first established, this rider escorted both passenger trains to Chambers Street AND freight trains. You will note in a lot of images; these riders appear quite young. They were - back in those days when a lad was old enough to ride a horse, he was old enough to work. It was not until 1938 that the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed, prohibiting most children under age 16 from working (with exception to agriculture and domestic labor). So a lot of young men, no older than their early teens; were seen at work and this position was no exception.

. The following film, converted to digital format, shows several of the West Side Cowboys at work escorting the trains. The following digital video from the blog "LivinTheHighLine" article titled "The West Side Cowboy and the High Line", (www.livinthehighline.com/the-original-urban-cowboy/). This image below, coincidentally visually exemplifies how pedestrians got injured or killed on the streets on their own accord. In this image we clearly see an escort to the train with red flag warning the public about the oncoming train (moving at no more that 6 miles an hours per City ordinance); yet in that brief span of time between that escorts passing and the train following behind, a Department of Street Cleaning (predecessor to the Department of Sanitation) street sweeper and a pedestrian are crossing in front of the train. This was a decision - sometimes a fatal decision - made by the individual to take that risk. This is an exhibition of free will. And it was not the railroads fault. .. . The Situation Comes to a Head. And a leg. And an arm - the West Side Improvement Project(s): Hell's Kitchen / Chelsea as well as Riverside Drive, Manhattan

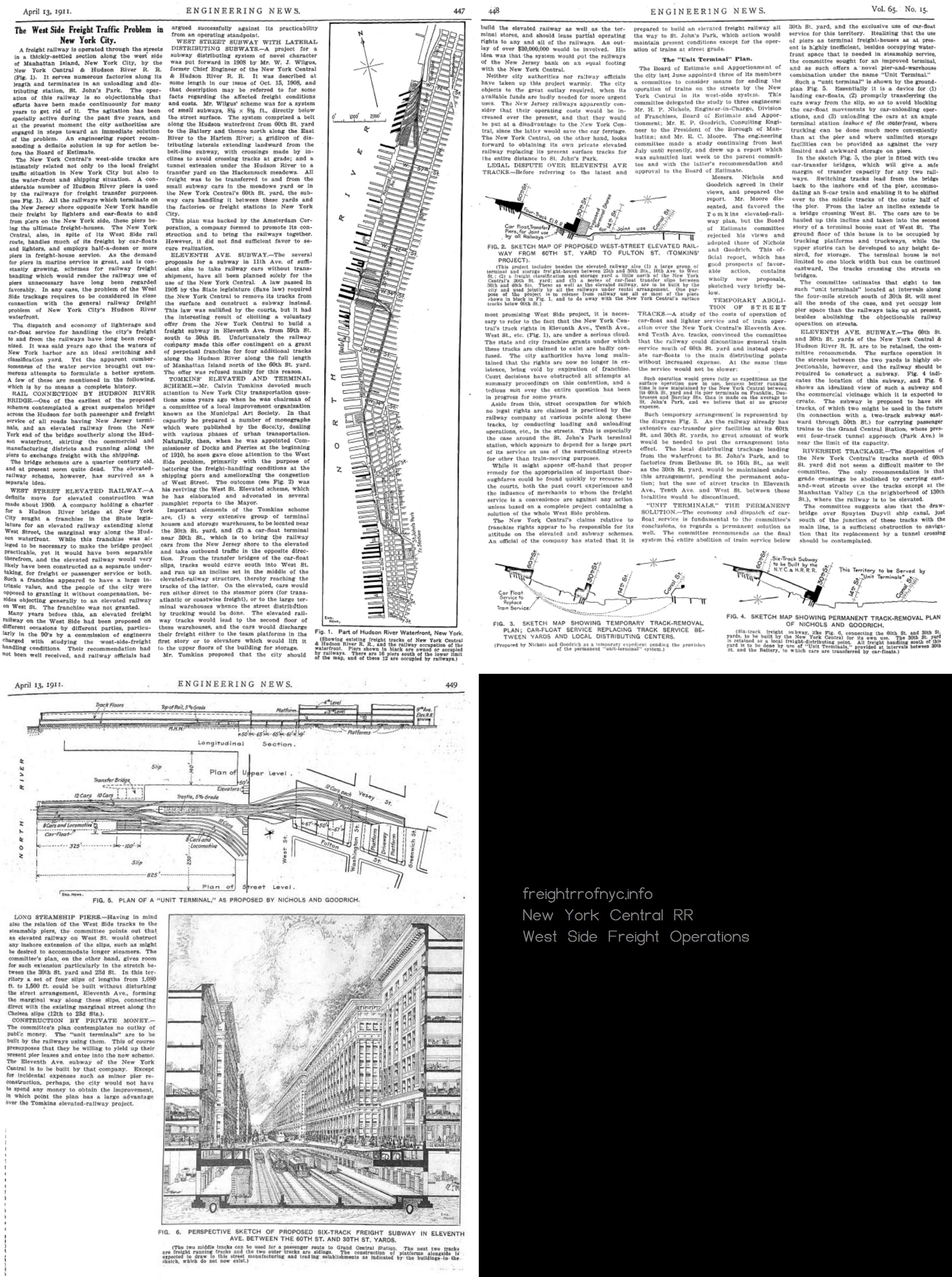

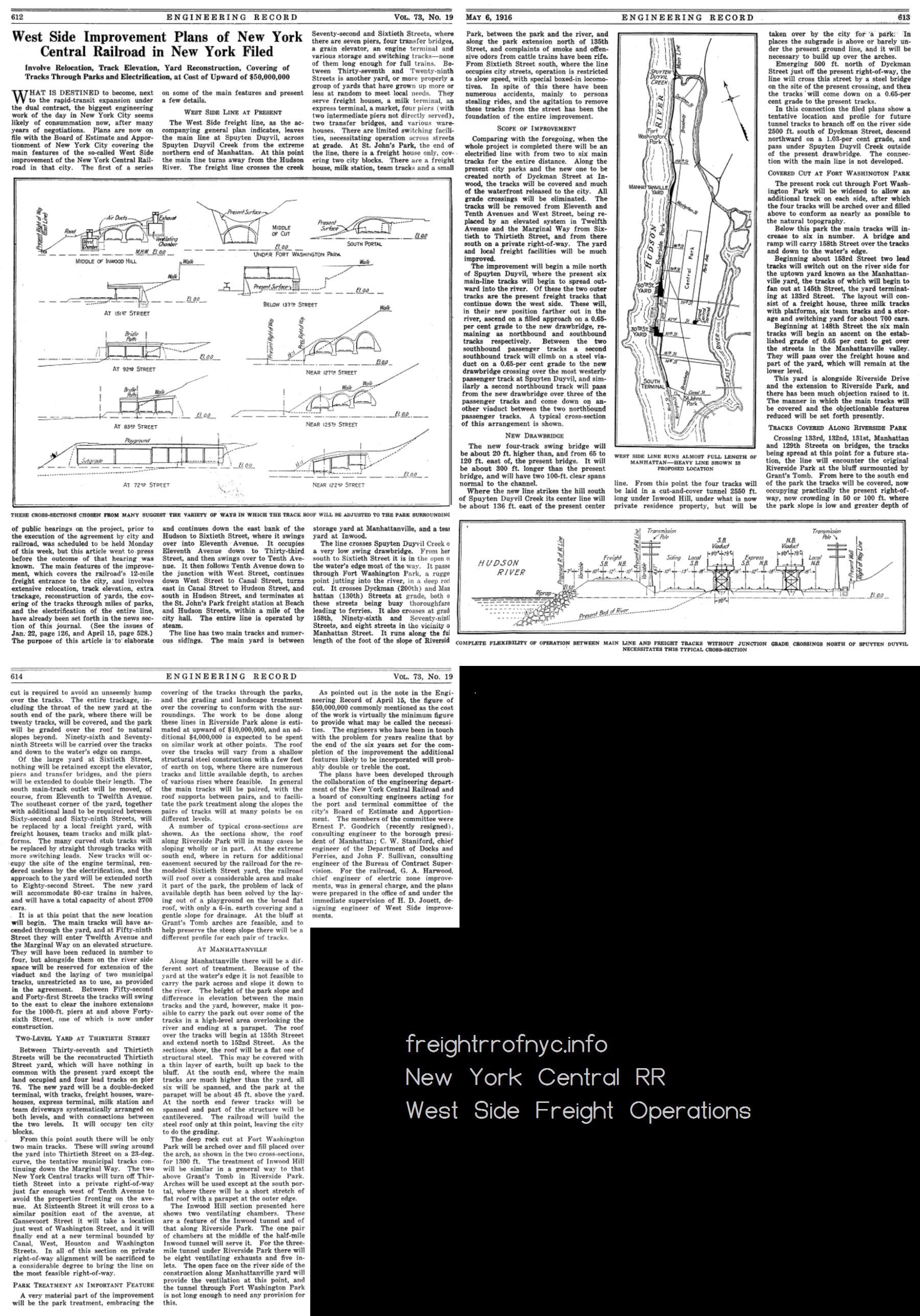

. 1911

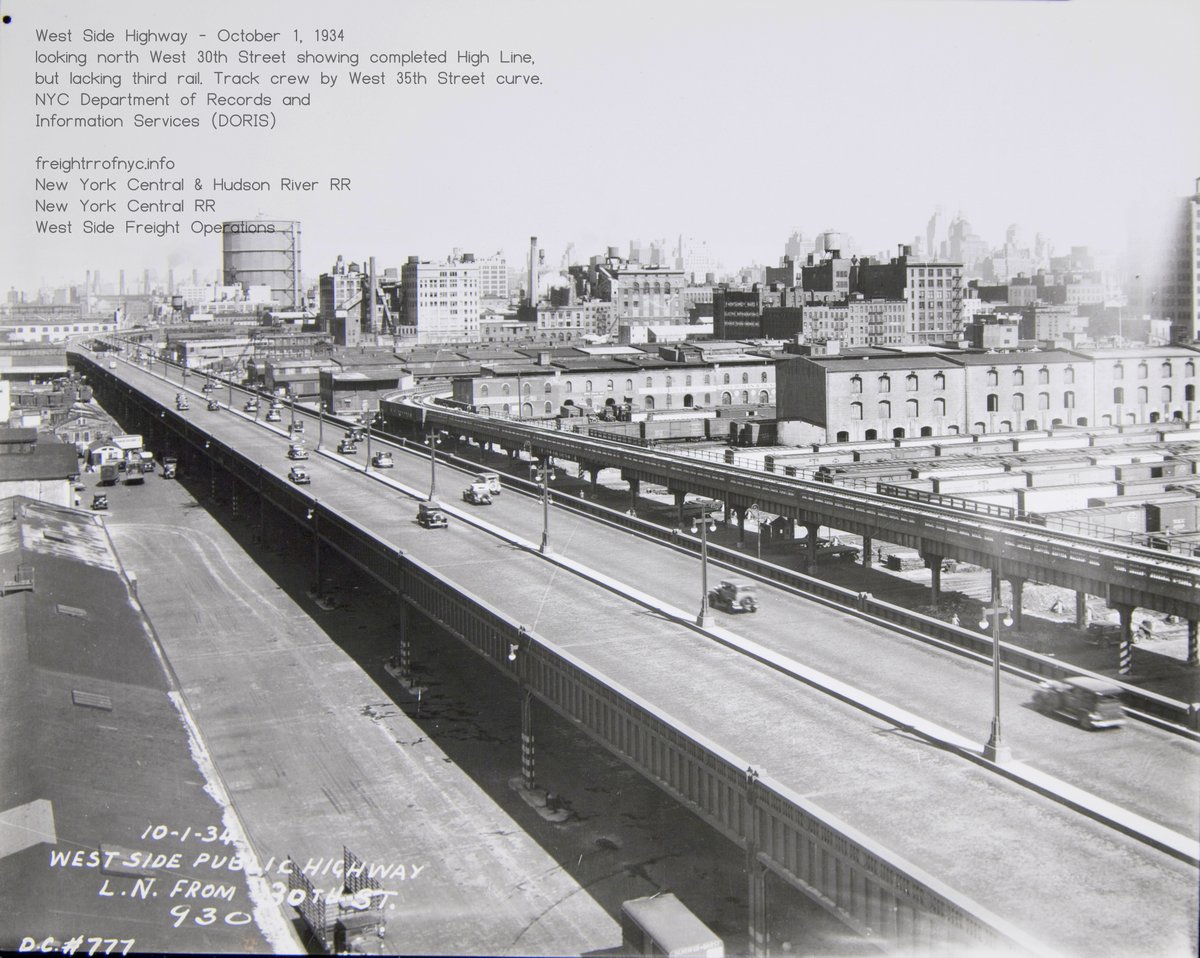

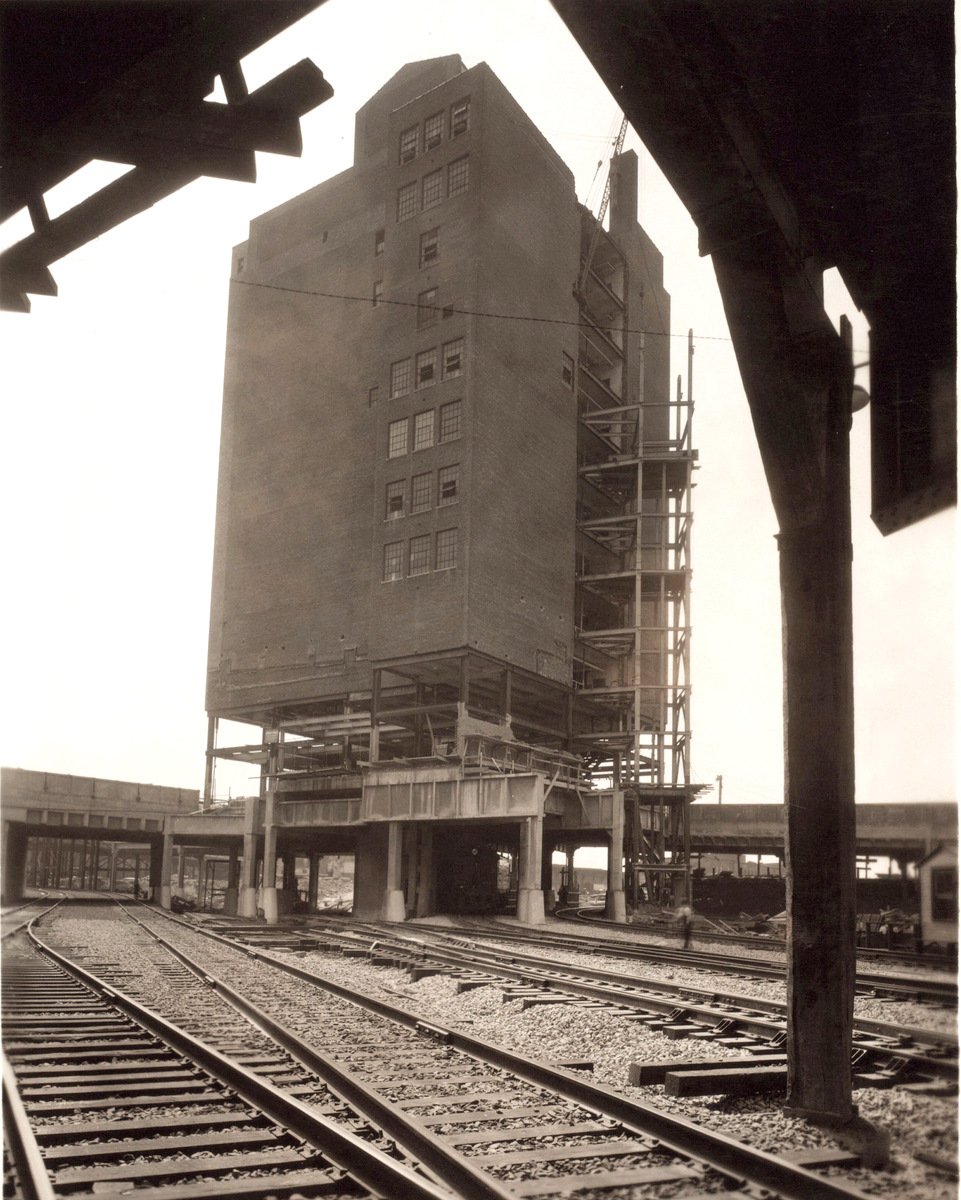

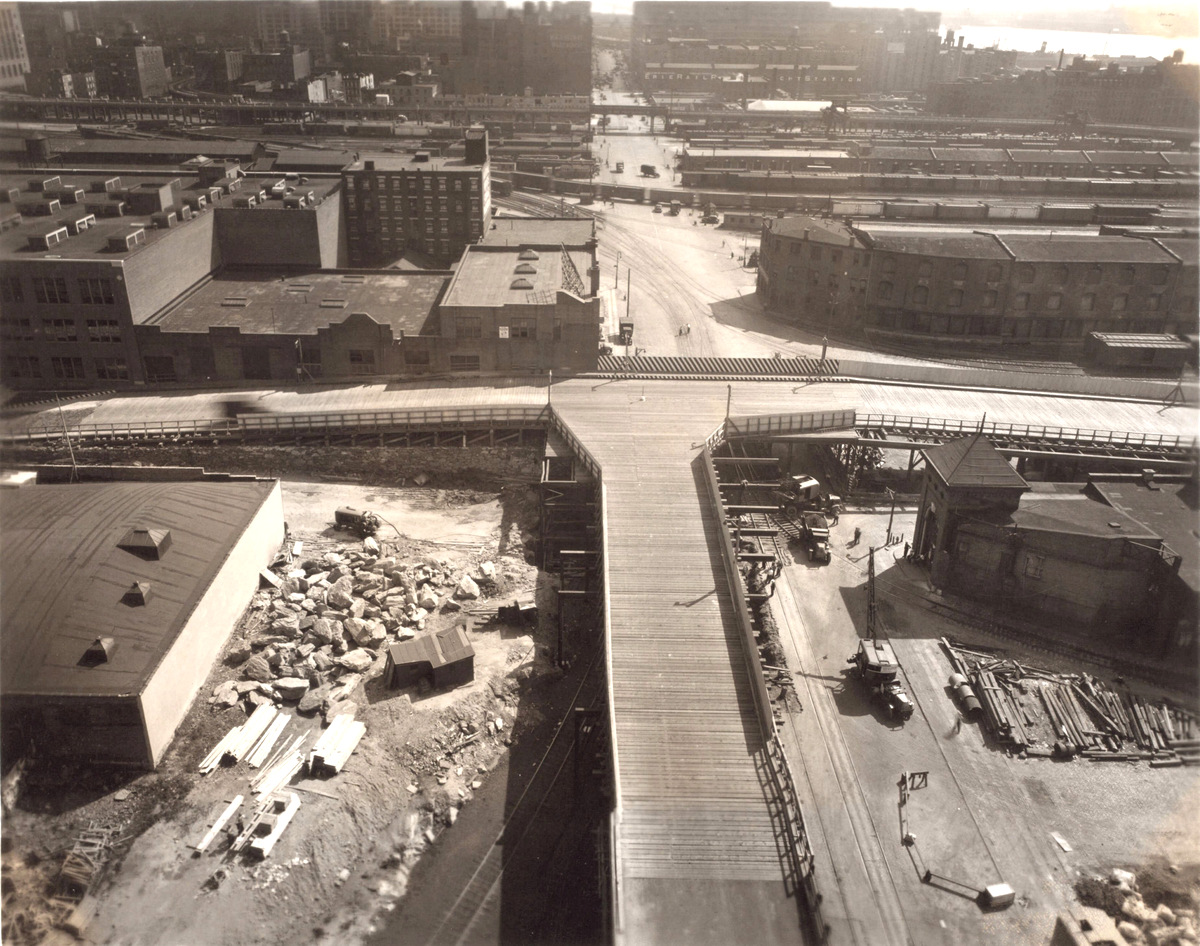

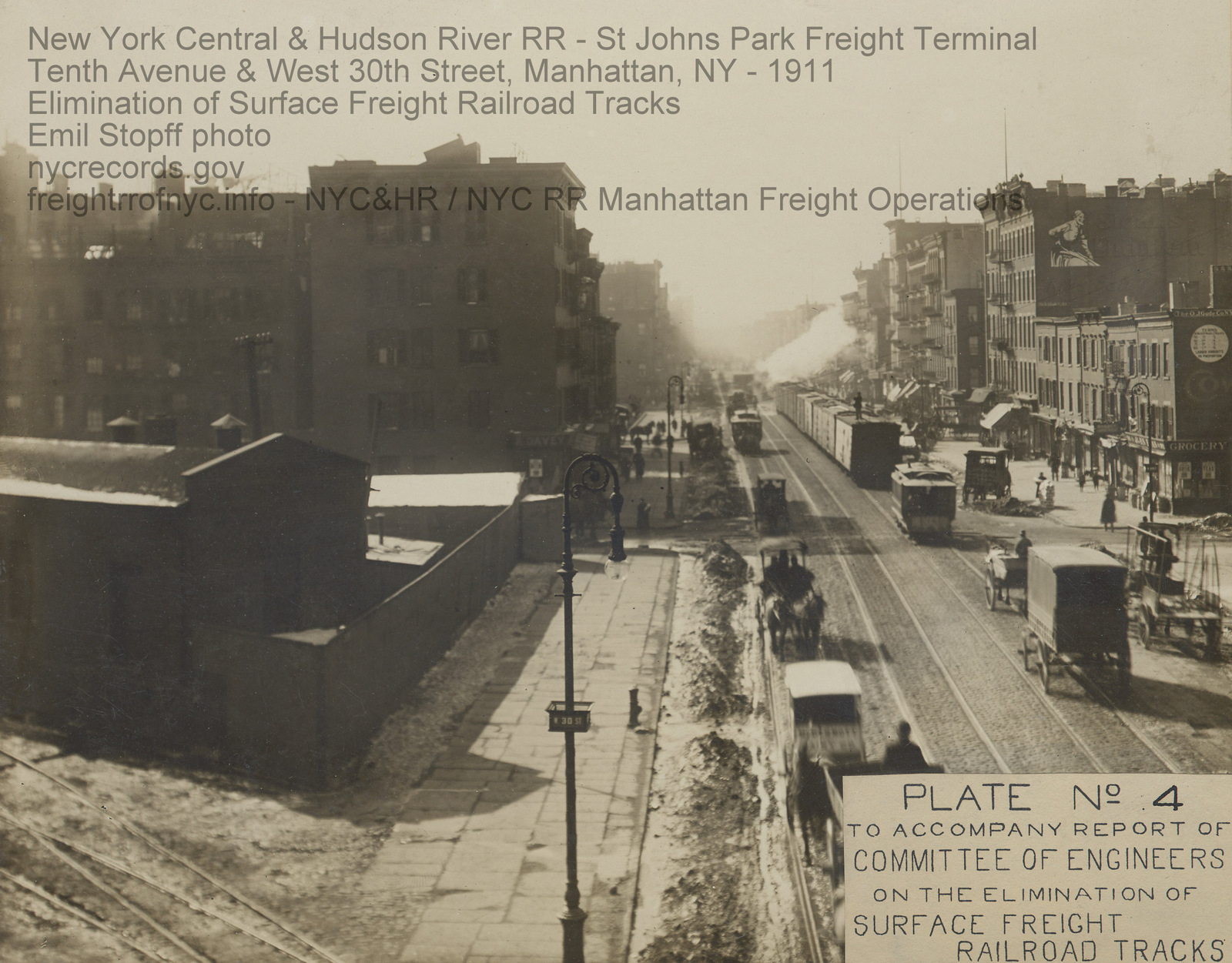

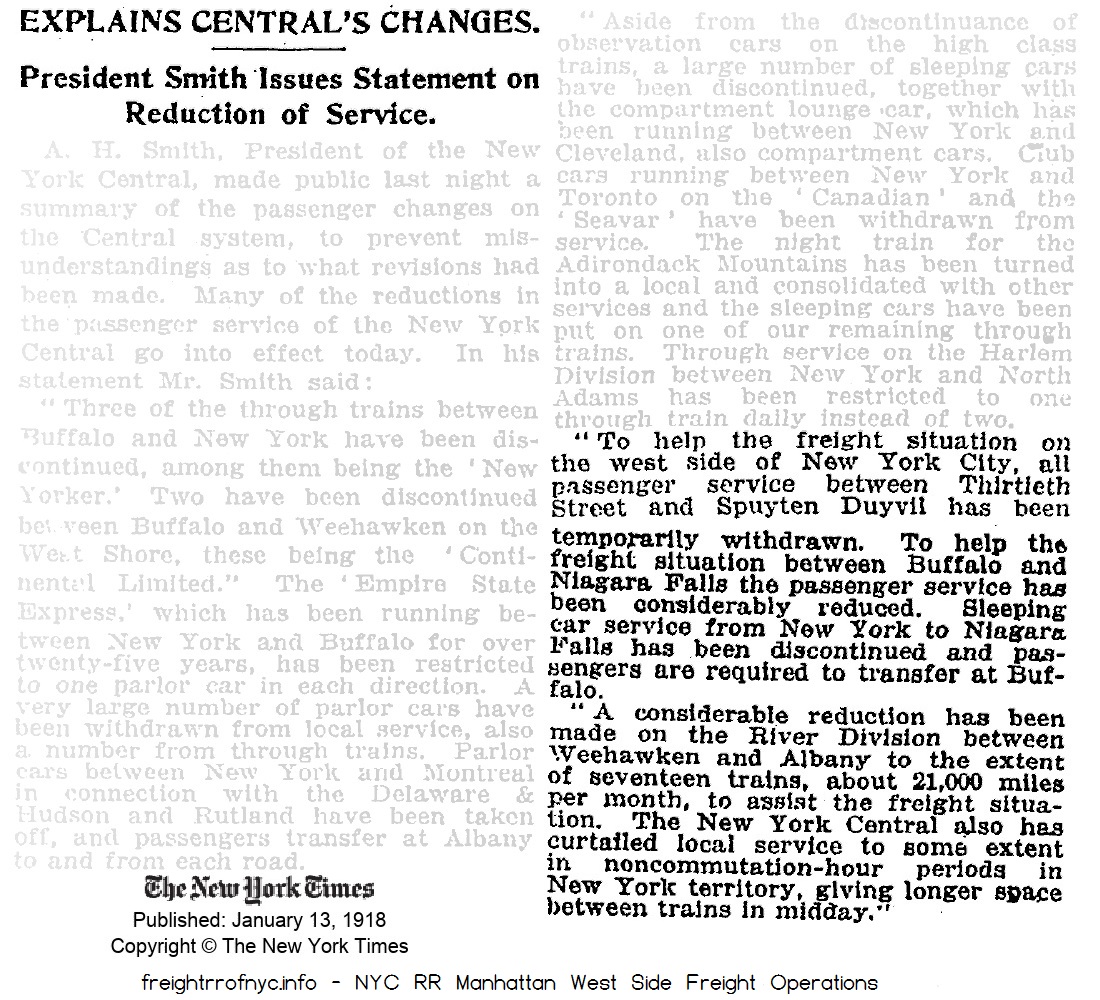

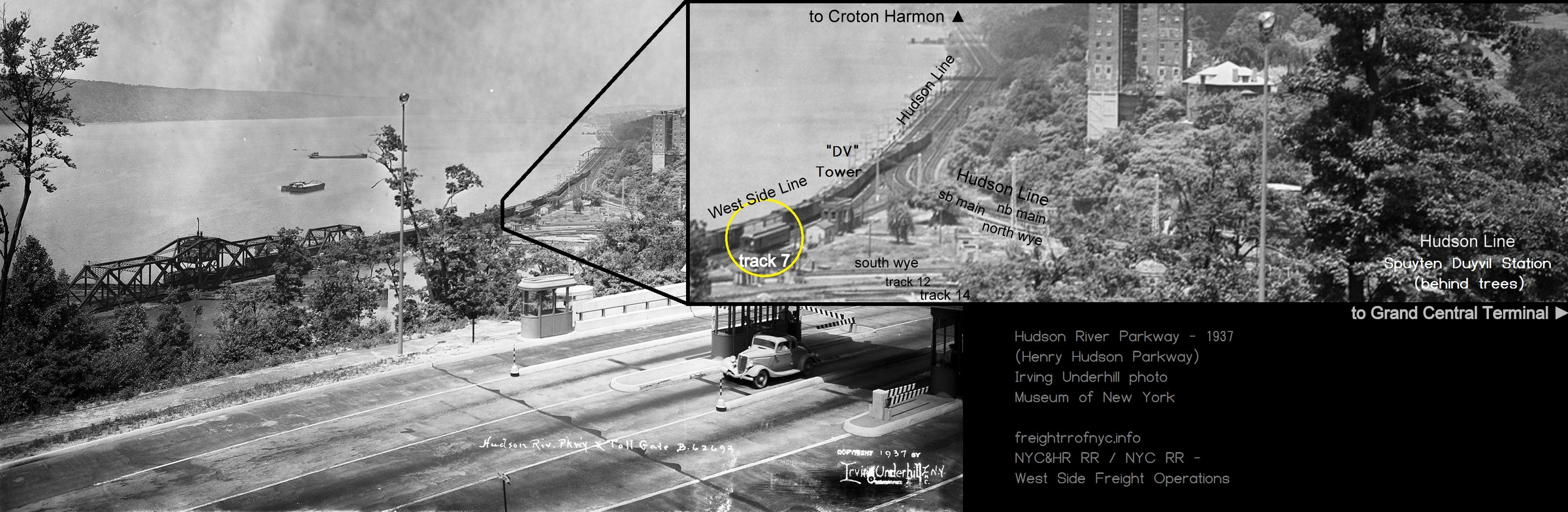

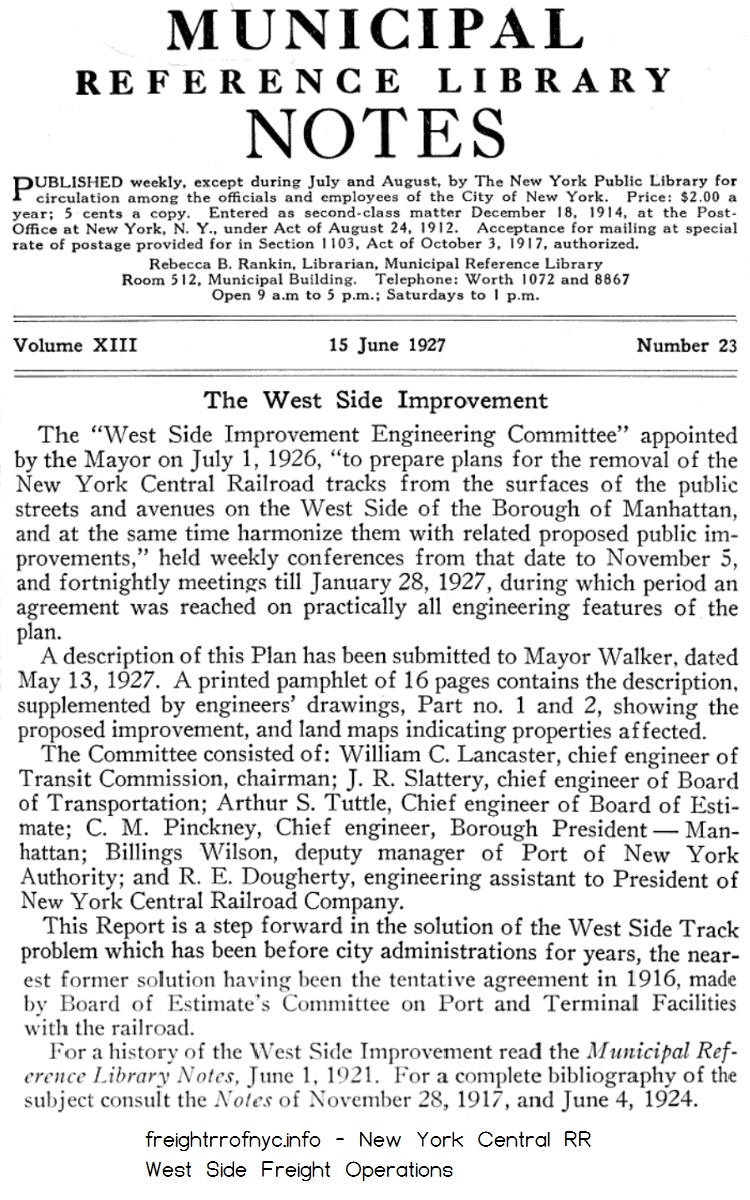

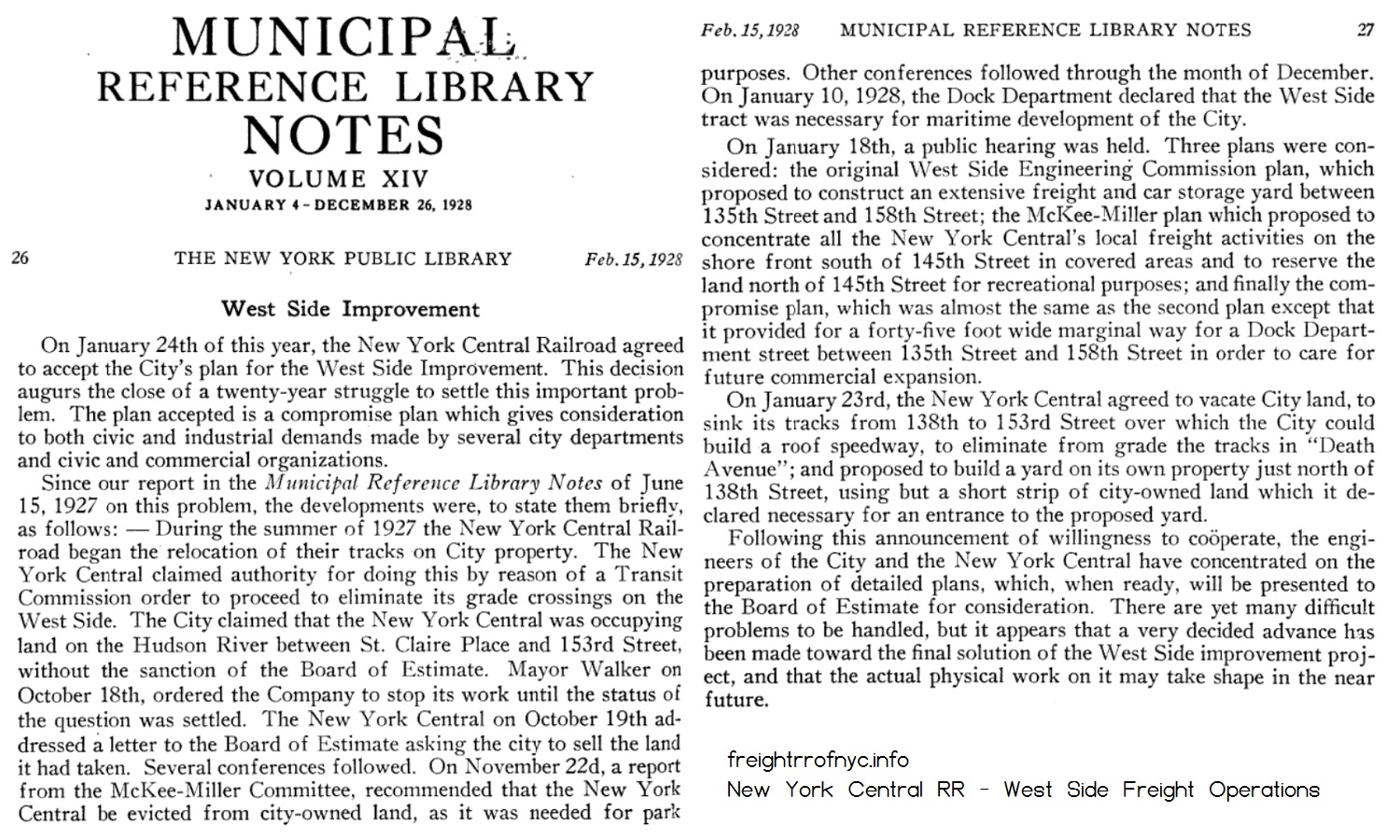

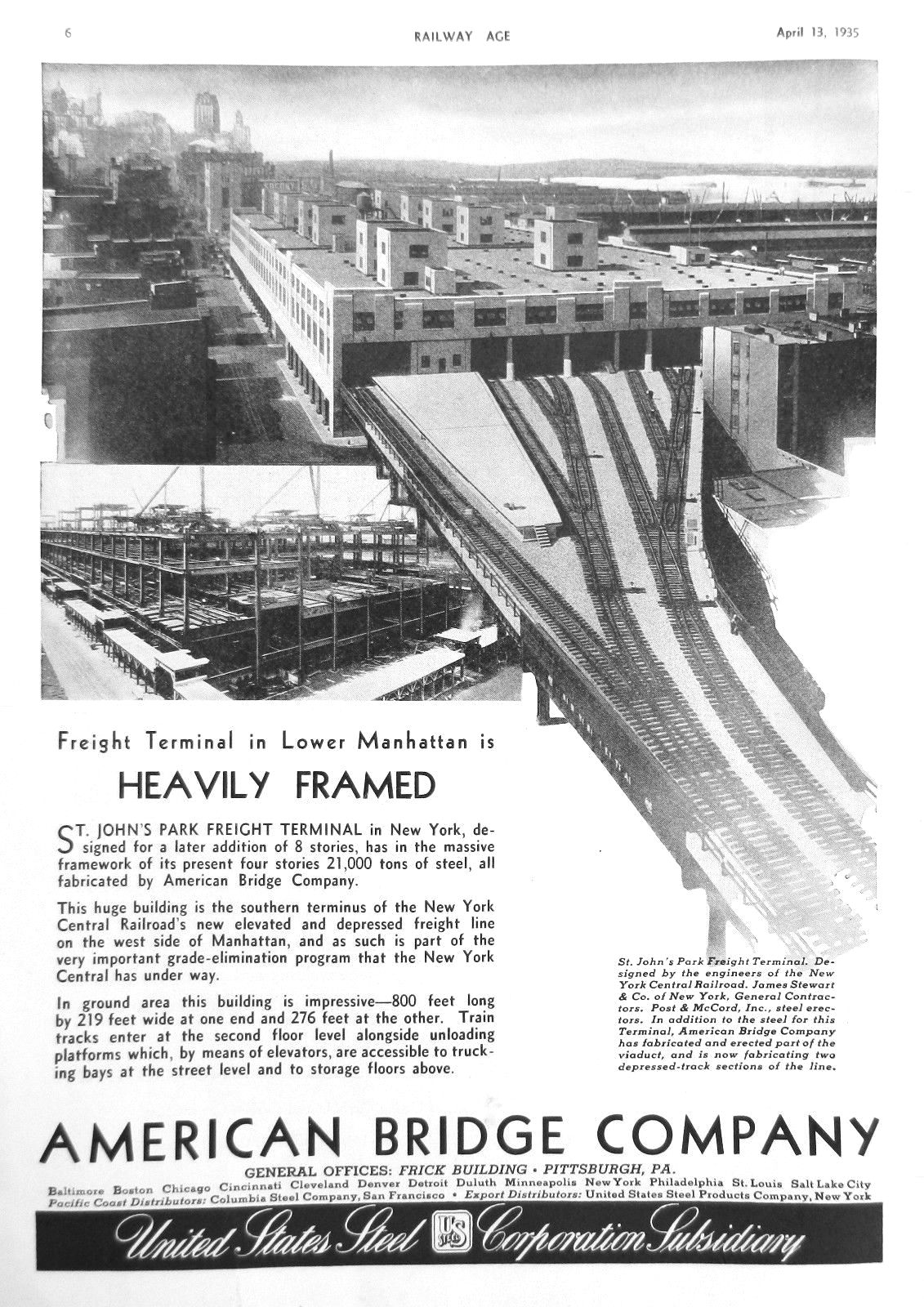

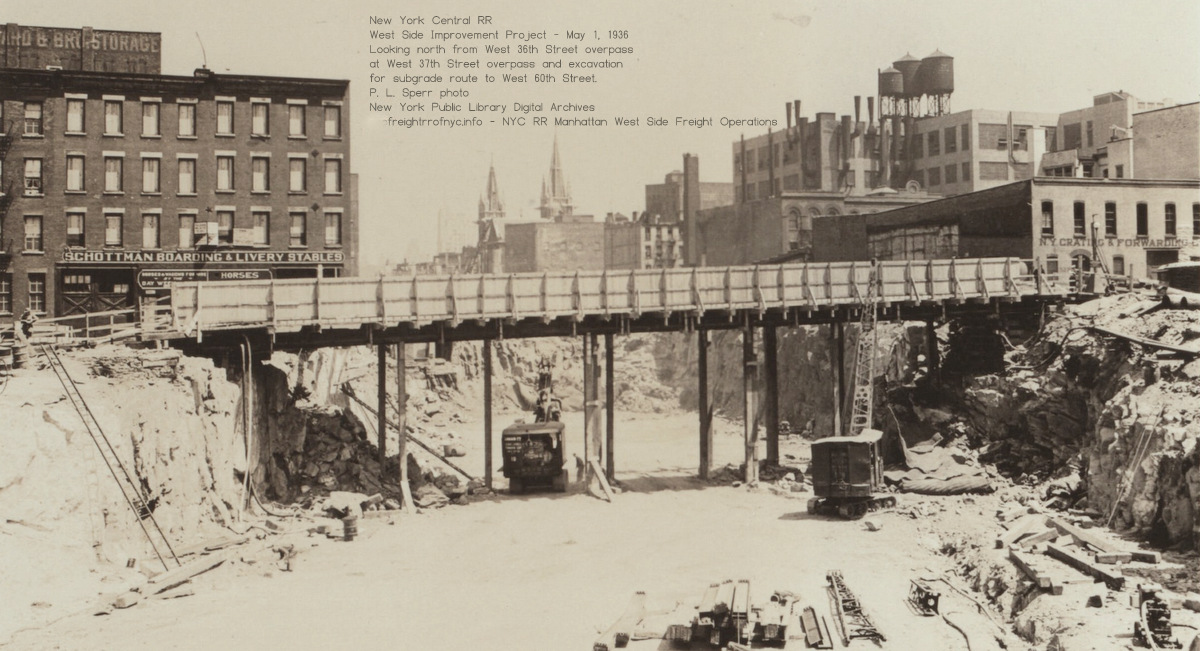

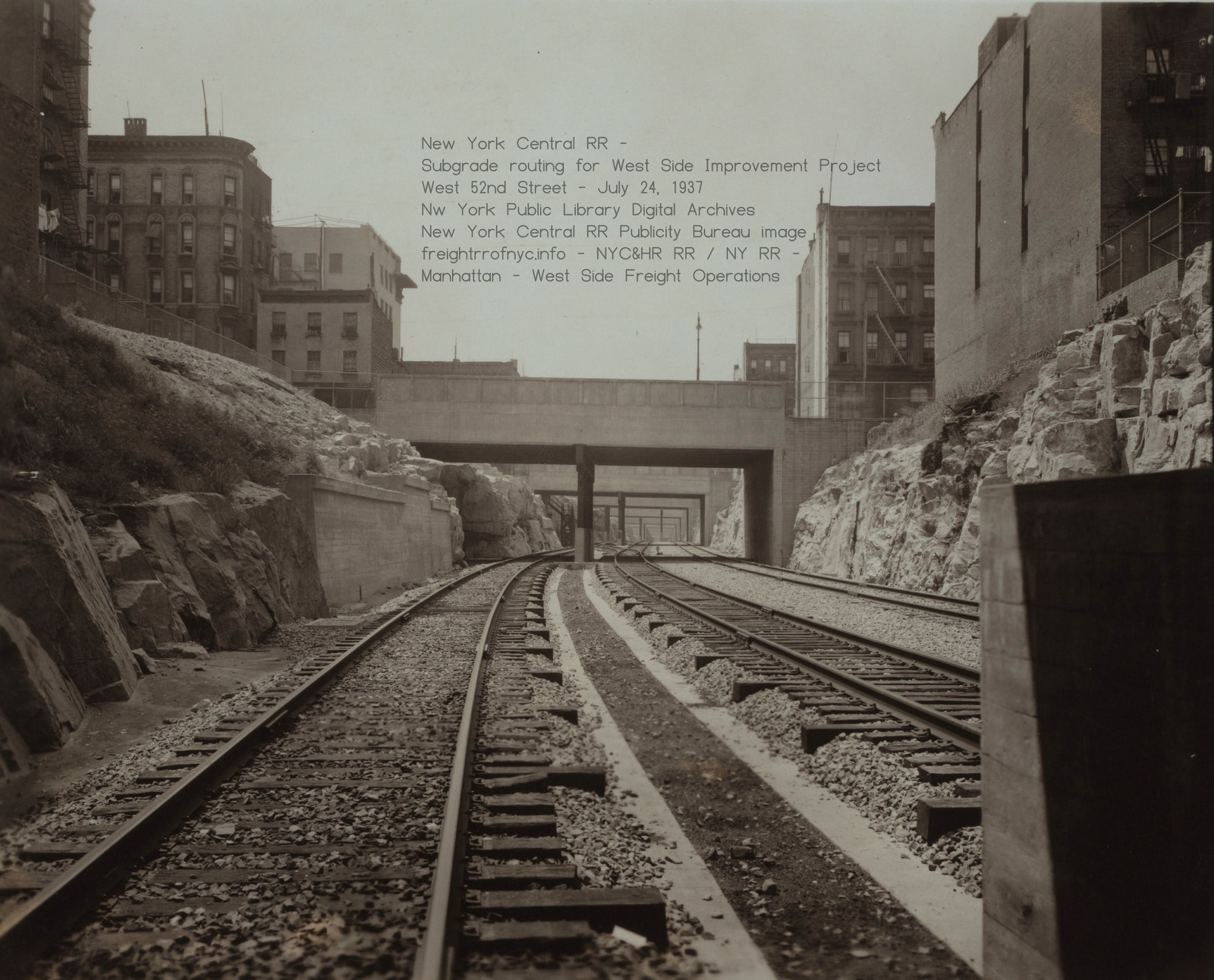

Thereupon the Legislature of 1911, by chapter 777, directed the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad Company to file before October 1 of that year; plans to show how it would remove its tracks, and authorized the Board of Estimate and Apportionment to enter into negotiations with the railroad to effect this. The situation then, in short was this: the City is trying to get the railroad off of its public streets; and the railroad company is trying to improve its freight terminal facilities. The question was, how can these two ends be attained and the interests of each conserved in fairness to those of the other? So, the new plan was thus: tracks to be placed in a roofed cut, designed to carry a motor parkway above, from Spuyten Duyvil to West 72nd Street, and then an elevated steel girder structure from 72nd to St. John's Park. But it was also stipulated that the trains be drawn only by electric locomotive after 1915, which the entire project was to be completed by 1917. The railroad and the city were getting close, but no cigar. Back to the table they went in 1916. Now it was proposed (from north to south): a tunnel under Spuyten Duyvil Creek (Harlem River) to a six track roofed cut to West 60th Street, then a four track elevated from West 60th Street to a point just south of St. John's Park, and an extension to Cortlandt Street carried on a viaduct above West Street and the bulkhead line. The railroad also took the moment to suggest enlarging their existing freight yards, and while they were at it; a provision for passenger service to the West Side to help alleviate the load from Grand Central Terminal. Total estimated cost? $65,000,000 dollars ($2,010,000,000 in 2024 dollars). Both parties agreed.  . 1916

Note that in the following two images, the tracks are significantly lower in elevation than that of the buildings. It was not like the trains were at their front door like in Hell's Kitchen or Chelsea. Also, when the trees were in bloom, the sight line changed, blocking more of the railroad from sight. Apparently this was not enough.  Riverside Drive looking north from West 74th Street - 1910 Library of Congress added 19 October 2025 .  Riverside Drive looking north from West 145th Street - 1911 Library of Congress added 19 October 2025   . 1917

Not so fast! In June 1917, the State Legislature in Albany first nullified that agreement, and second; required all future plans be submitted for review by an "impartial committee" and approval by the Public Service Commission (a State agency) The New York Central had been at the bargaining table with the City and State, because the City and the State of New York wanted the Central's railroad operations off the public streets as well as out of Riverside Park. By know, there were actually two battles being fought under the encompassing West Side Improvement Project:

Make no mistake, the New York Central wanted their operations off the streets of lower Manhattan as well; and as the City owned the streets, there was little recourse. As for the Riverside Park vicinity, the Central apparently owned it rights of way through portions of the park. When it came to who was going to pay for these "improvements", the railroad accepted the fact they would have to pay for most of it, but they rightfully were not going to pay for all of it. And the issue wasn't simply about money. There were also matter of property ownership and rights involved. The Central had property and rights that the City wanted, particularly through Riverside Park. The City had property and rights that the Central needed to relocate their tracks. The City; or more accurately, the community boards and resident organizations; were adamant about not giving up a square inch; "the parkland must be preserved." This left the railroad in a position frequently known as being between a rock and hard place. It could not relocate without some acquisition of land, and the City wanted the railroad to give up a lot of what it owned in the name of community improvements. The affluents that resided along Riverside Drive were adamant about not giving up and city parkland for the railroad, but yet they wanted the railroad to move. That is pretty much it in a nutshell. One of the more succinct outlines of the issue comes from the following document: West Side Improvement - 22nd Annual Report of the American Scenic & Historical Preservation Society - 1917 but I warn you, its 32 pages in length. That demonstrates how complicated the issue was. And in April, the United States entered World War I and changed the priorities for several years. But, while both minor dithering between the City and the Railroad commenced, and some major dithering in Europe; the freight demands of Manhattan was growing at an exponential rate. Thus began over a decade of negotiations, plans, counter-plans, court hearings and compromises; before an actual shovelful of dirt was moved. The specific details are contained within the following three references (the first two of which are open source):

As I pour over documents and the more I witness; the railroad (as greedy as railroads could be) was really at the negotiating table trying to make the West Side Improvement Project(s) work. With every change of City and / or State administration however, the politicians wanted more "givebacks" by the railroad and less "give in's" by the City. This is to say nothing of how the City of New York was going to finance their share of the improvements. As a result, many different plans were put forth over that period of time from 1909 through 1920. Some within reasonable expectations, some purely in outer space. . . 1920

In April 1920, Alfred H. Smith put the case quite succinctly in an address at the Merchants Association of New York City: "Manhattan Island lives on a hand to mouth existence. Because of the dearth of warehouses and storage facilities and of modern equipment for handling freight. The unnecessary costs and losses yearly are prodigious; [and] none but a rich and growing city could have borne the burden." In other words, because of the warehouses and storage facilities on the island, the City feeds and clothes itself from outside supplies. Remove the railroad, and you remove the warehouses and industries and income for thousands of people who work at these facilities. Remove that and the city withers. This statement followed another in which the endless delays of the City and State of New York was criticized and the United States Railroad Administration refusing to grant increases in freight rates, comparable to those in wages. It was in short, a statement made to the effect of "shit or get off the pot." One plan put forth, had the railroad completely sub-grade starting with a tunnel that went under the Harlem River and Spuyten Duyvil; all the way to at least, the West 30th Street Yards. The plan was for the City to build the tunnel, with freight stations alongside the route, and they would lease the railroad yearly rights to operate their trains there. Another plan was for an elevated railroad from Spuyten Duyvil to West 72nd Street, then enter a subway with service through the basements to those buildings desiring such service. Much like todays passenger carrying subways in New York City, only substituting people for freight. A more realistic plan was retain the existing bridge at Spuyten Duyvil, with the tracks sub-grade from there to West 60th Street; then an elevated line from West 60th Street to St. John's Park. Two of the more audacious plans were outlined in the New York, New Jersey Port and Harbor Development Commission Joint Report with Comprehensive Plan and Recommendations - 1920; on pages 231 and 239. The estimated cost of the elevated plan, was $262,000,000 (adjusted for inflation for 2025: $4,244,085,600). The tunnel proposal was estimated to cost $250,000,000 (2025: $4,050,000,000 - and I haven;t quite figured out how the tunnel plan was cheaper than the elevated - tunneling is always more expensive. A similar plan to these, yet substituting cable driven narrow gauge carts is also shown on page 269. Well, one can dream, no? From what I gather from the synopsis of the following document, it really wasn't the railroads fault. Each City administration wanted "their vision" to be the one that was implemented. Then, with each City agency that became involved, no one really knew who had jurisdiction: "In 1911 (chapter 777 of laws of 1911) the West side Improvement was made the subject of special legislation, and the carrying out of the improvement was left generally for direct action between the City authorities and the railroad company. Under the Mitchel Administration plans for carrying out the West Side Improvement were developed in great detail, but at the last the proposed arrangement failed of approval. In 1917, the special legislation of 1911 was amended to confer certain jurisdiction of the (state) Public Service Commission for First District (chapter 719, laws of 1917). On another front, an agreement would be reached, whereas the State of New York was to pay one quarter of the cost of this grade separation / realignment project, the New York Central Railroad was to pay three quarters. And true to fashion, the State of New York balked, stating it did not have the funds to cover their full 25% portion. With surprising congeniality and good faith, the New York Central Railroad offered to cover the States' portion and defer reimbursement arrangements and repayment to a later date. Not surprisingly, I cannot locate any documentation alluding that the State finally paying its due share of apportionment, but it may have been paid in installments or reduced taxation. Then a plan arose that a double decker highway and railroad elevated be constructed. This plan would eliminated most of the grade crossings on Twelfth Avenue, but did little to ameliorate the issue between the pedestrians and horse drawn traffic at street level at Midtown. This plan amounted to only the Miller or West Side Elevated Highway being built for automobile traffic only. So, back to the bargaining table they went. The goals of all were to get the trains off the street, and who was going to cover the municipality's fair share of fiscal responsibility. .. . 1923

In 1923; the State of New York reviewed the proposals and the New York Central Railroad now proposed the following: a new line of 11 miles in length consisting of the following: a new swing bridge at Spuyten Duyvil (eliminating the expensive tunneling) a roofed cut through Riverside Park, expansion of the existing freight yards, a viaduct from West 72nd Street to a completely new freight terminal located south of Spring Street and the razing of the old St. John Park's Terminal. And now yet comes another monkey wrench gets thrown into the West Side Improvement plans. . . 1923: The Kaufman Electrification Act - Now all steam locomotives are banned in Manhattan. Or are they?

Put into the simplest terms; the Kaufman

Electrification Act of 1923,

ratified by the New York State Assembly; was the act that mandated that all railroads

located

in the City of New York City be electrified by January 1,

1926, and by proxy tried to eliminate steam locomotives.

A great deal of misinformation exists about the Kaufman Electrification

Act, or simply "the Kaufman Act". This misinformation circulates

both in general discussion of New York City history, as well as within

railroad historical

contexts. All too often, it's simply stated "steam locomotives were banned in Manhattan in 1908, blah blah blah". This is simply not true. Being that the Kaufman Act bears a great deal on the history of the New York Central's operations in Manhattan, I cannot suggest strenuously enough, that that history needs to be read. I will attempt to address the high points here however, but a few paragraph synopsis will not convey the details as much as I would like them to. Now, the New York Central was essential fighting a multi-front war:

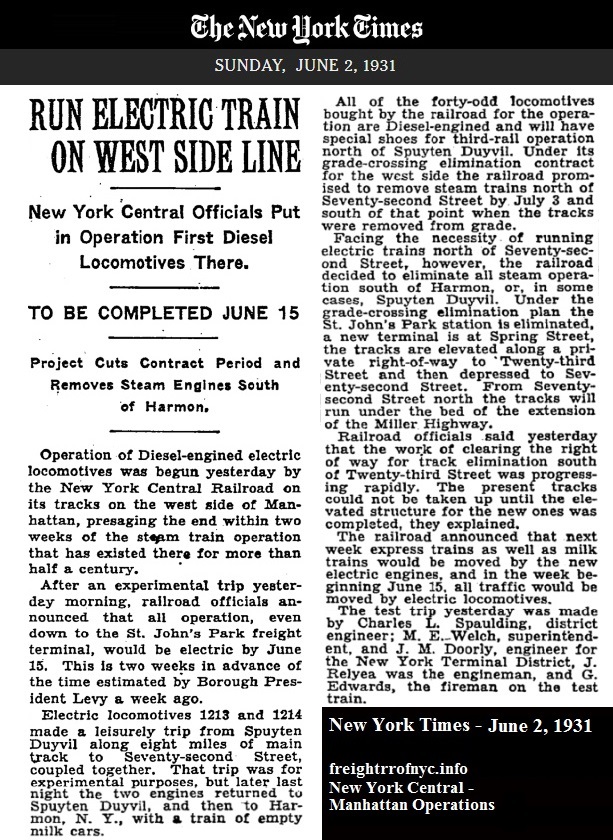

The Kaufman Act as ratified by State of New York on June 2, 1923; was now demanding electric operation of all trains within the City limits of New York by January 1, 1926: yard, passenger, freight, main line, switching, everything. This Act appears to have been an end run around the West Side Improvement Project process, which was taking forever through city agencies. In short, so many city agencies were involved, it became confused as to who had jurisdiction. The Kaufman Act, a state act; started with only electrifying the New York Central trackage north of West 72nd Street running through Riverside Park. But within weeks, it morphed into dictating policy for every railroad in the City of New York, not just in Manhattan; and it attempted to force them to use a single type of power: electric. Governor Smith signed the Act "as is": the Kaufman Act as written and ratified, provided for no time extensions, and for all railroads to be fully compliant by January, 1, 1926, with electric locomotives. Any railroad not in compliance was to receive a $5,000 per day, per occurrence fine. It was heavy handed and ham fisted. Obviously, the railroads had something to say about this. Multiple railroads operating freight terminals in the City of New York vehemently objected to the Kaufman Act, and the most outspoken of all was the New York Central; as most of their trackage was in the streets. The use of a ground level electric third rail was not feasible (unless you wanted to electrocute some residents on a daily basis - the cure was more deadly than the disease); overhead trolley wire had already been forbidden in the City for two reasons: the foremost was due to stray electric current finding its way through gas mains and prematurely corroding them; the second was out of a concern about telephone and telegraph wires falling on the trolley wire and transferring the high voltage to a telephone / telegraph handset. Electric battery locomotives were not sufficiently advanced to consider for heavy freight use, and neither were compressed air, fireless steam or gas mechanical locomotives. Think about this: here we are in 2024, 100 years later, and battery locomotives still are not reliable enough to warrant widespread use or acceptance in a freight railroad capacity! The first amendment to the original Act, dated 1924 and filed by Kaufman; was nothing more than to expand the regulation: from the City of New York (Manhattan, the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island) to now include neighboring parts of Westchester County: Yonkers, Mount Vernon and New Rochelle. Obviously, this amendment was not in the railroads' favor. On December 31, 1925, a temporary injunction sought by the railroads was issued, based on the unconstitutionality of the Kaufman Act. The railroads maintained that the excessive fines were tantamount to violations of unlawful seizure. In addition to this, they also stated the federal Interstate Commerce Commission had until this point be the ruling agency regarding locomotives and safety appliances. The injunction was granted with decision reserved (to be decided at later date). This temporary injunction was made permanent on March 26, 1926; the Federal Government had jurisdiction over locomotives and interstate commerce, not the State of New York. It did however dismiss the claim about unlawful seizure. The second amendment to the Kaufman Act, ratified in May 18, 1926; was in favor of the railroads, and it granted them a five year extension for compliance with the Act. Contrary to public misconception, this second amendment was not about adding diesel-electric locomotives to the list of approved power sources. The amendment was strictly to provide a five year extension to the 1926 effective date. The diesel-electric locomotive was becoming a viable alternative to steam and electric propulsion, and provided a means for the railroads to comply, and was recognized as such by the chief engineer of the Public Service Commission, William C. Lancaster. He recognized this new form of motive power. The Public Service Commission was the state agency responsible for enforcing the Kaufman Act. . Fortunately, the State was now knocked out of the box by the federally issued injunction. And despite the State granting a 5 year extension for compliance; the railroads maintained their steadfast opposition to the Act. Let us turn back the calender a little to 1924; a prototype General Electric - Ingersoll Rand model X3-1 locomotive, better known by its construction number: #8835; was fitted with an inline six cylinder (10" x 12" cylinders) diesel engine constructed by Ingersoll-Rand utilizing the Price-Rathbun design and solid injectors. This engine in turn powered an electrical generator designed by General Electric. This in turn supplied electricity to traction motors with voltage and current being regulated using controls designed a few year prior by Hermann Lemp of General Electric. The carbody was a left over, laying around at General Electric's Erie, PA facility. #8835 would be "unveiled" on February 28, 1924 to the representatives of the railroads showing interest in a diesel locomotive: Baltimore & Ohio, Pennsylvania, Boston & Maine, New York Central, Reading & Lehigh Valley. While the men were impressed, they remained unconvinced of the design which had not yet seen day to day service. So, beginning in June 1924, and for the next thirteen months, the unit went through rigorous (and to some extent, abusive) testing on ten different railroads and three industries (to which the locomotive had been leased on a trial basis). #8835 would come to spend 2½ months operating on the West Side of Manhattan along Tenth and Eleventh Avenues for the New York Central Railroad, the most out of all the locations it would be tested at:

At midpoint of its testing on the 'Central; this locomotive was placed into a "tug-of-war" test with one of the a Shay type locomotives of New York Central working the West Side Line; in which 8835 won that battle due to smoother torque of the electric drive and greater coefficient of friction; and a little overzealousness on the part of the Shay's engineer, who got the Shay's wheel's slipping. Needless to say, the Central's men were very impressed, as well as the other railroads. Most of the railroads that were going to be effected by the Kaufman Act, placed orders for the A/GE/IR switcher. But the New York Central held off committing. As stated, the Central Railroad of New Jersey received their A/GE/IR Boxcab and placed it into service on November 2, 1925. THEN the second amendment to the Kaufman Act took place on December 31. With a successful injunction in their pockets, and holding off the demanded changes stipulated by the Kaufman legislation by 1926; the railroads continued the legal battle to invalidate the Kaufman Act. Perhaps the Governor of New York, Alfred Smith; either was astute enough on his own (or had some cronies whisper in his ear) that perhaps the Kaufman legislation as written, was flawed as the railroads had been stating. This is because Smith first vetoed a measure the previous year requesting an extension, because "the railroads had nearly a year to demonstrate they were attempting to comply with the provisions," however, but this time around, Governor Smith approved the amendment because, as he stated: "that the task imposed upon the railroads is a difficult one because it involves not only the question of electrification but also that of the grade crossing removal."The US Statutory Court found the Kaufman Act unconstitutional. The specific reason was the Federal Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had jurisdiction over locomotive use on railroad operations, on the grounds they constituted interstate commerce, and that the ICC had already legislated various safety appliance regulations on and for the railroads. That meant the State of New York did not have authority to determine what type of locomotive could or could not operate. The City of New York belonged to the State of the New York, the State of New York belonged to the United States of America. And so, on September 9, 1926; the US Statutory Court, with the Honorable Learned Hand presiding, along with two other judges; stayed the injunctions against the Kaufman Act permanently. In light of this, the State of New York formally repealed the Kaufman Act in 1930. (there are other events proceeding this, but have no reflection on the New York Central, so if you are in fact interested in learning about them, please go to the Steam Locomotive Legislation and Regulations in and around the City of New York page itself. With the federal court staying the injunction against the Kaufman Act; the other railroads could now breath a sigh of relief; but the New York Central was not out of the woods. It was still locked in a battle called West Side Improvement Project - getting the trains off the streets. Now quite a few of you will ask, if the railroads were no longer bound by the Kaufman Act, why did they switch to diesel locomotives? Economy. Ease of operation. Ease of maintenance. Equal power to that of steam, perhaps even better. And the New York Central and New York City made a gentleman's agreement - the New York Central would remove steam locomotives in Manhattan by 1931. And so the electrified the West Line from Spuyten Duyvil to West 72nd Street by 1931. Electrification south of West 72nd Street however, would take until 1934 to get accomplished. With that explained, let us get return to the Riverside issue of the West Side Improvement Project. ..  Riverside Park - 1925 Looking north. Brown Brothers image courtesy of KermitProject.org added 19 October 2025 . Upon undertaking research for this particular chapter, I found myself inundated with hits and results of newspaper articles about the struggle to get a plan, any plan; approved. What is particularly interesting to read, in several of the articles was the moderation as willingness to negotiate of the part of the Central. And as you will read for yourself, it was the shenanigans and lack of unified jurisdiction between the City agencies that kept delaying things. Please keep in mind that most of the newspaper articles shown below were published the day after a proceeding or vote took place.

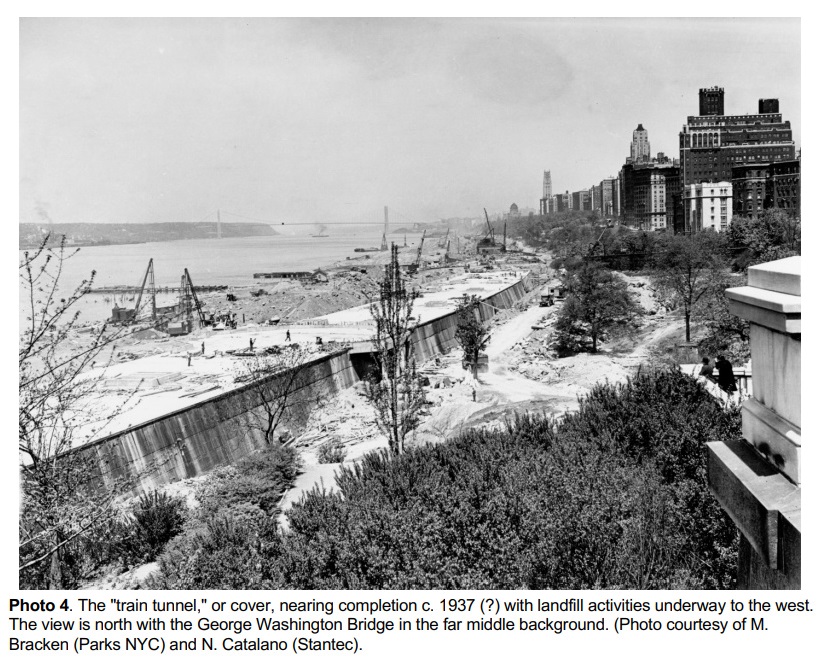

.  Excavation and grading of the new right of way in Riverside Park, approximately 75-100 feet east of existing tracks - July 11, 1931 Excavated material is brought across the tracks to shore line and dumped to increase shoreline area P. L. Sperr photo New York Public Library Digital Archives added 19 October 2025 .  Works Progress Administration Laborers working at Riverside Park - May 16, 1934 New York City Department of Park & Recreation added 19 October 2025 . Once this was agreed upon, the new right of way was excavated, graded and the new trackage laid. The original plan as designed, is described as comparable to a two level Roman aqueduct without the tall support columns: the trains would run through along the bottom level, and automobiles on the top level. Pedestrian tunnels built at regular intervals under the railroad tracks would grant residents access to the waterfront.was to build stone walls with arches on the west side of the railroad right of way, with Romanesque arches that intervals to allow the tunnel to ventilate. The east side wall would be solid stone or concrete. Steel I beams would be laid across on top, and when paved over, a roadway was planned to run along the top of the tunnel:  Google Maps added 19 October 2025 . Work between 72nd and 79th Streets was well underway in 1934 when Robert Moses was appointed City of New York Parks Commissioner; and he put an immediate halt to the project calling it a "visionary scheme." His view was that the highway on top of the tunnel would divide the residents from the park and waterfront, despite the many pedestrian tunnels that were planned to run under the tracks giving those residents access to the shoreline.  Stantec Consulting Services - Pre-Scope investigation of Reconstruction of Drainage Systems In Riverside Park, Archeological Assessment of 2022 His plan was move the highway to the very shoreline itself (which was one of the original sticking points to approving the Project back in 1929). This in effect defeated the very purpose of burying the railroad to give residents access to the shore to begin with! Moses would however retain the railroad tunnel and cover it with earth making additional parkland or pedestrian paths, tennis courts and recreation areas. The City approved this $11,000,000 plan with little to no opposition (anyone surprised?) And so construction resumed. Concrete walls were poured to either side of the tracks, covered with an I-beam and back filled with earth, thereby making a tunnel.

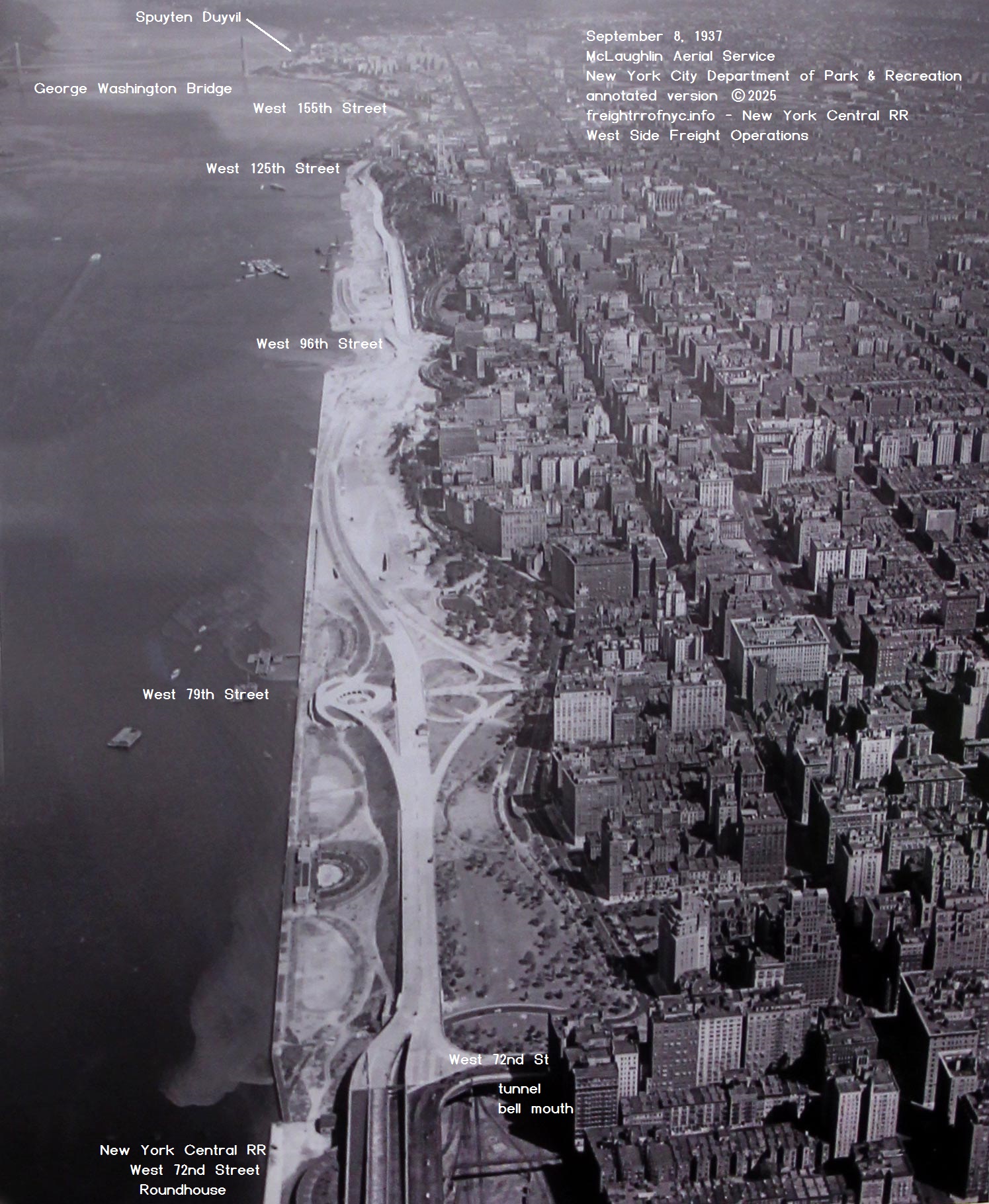

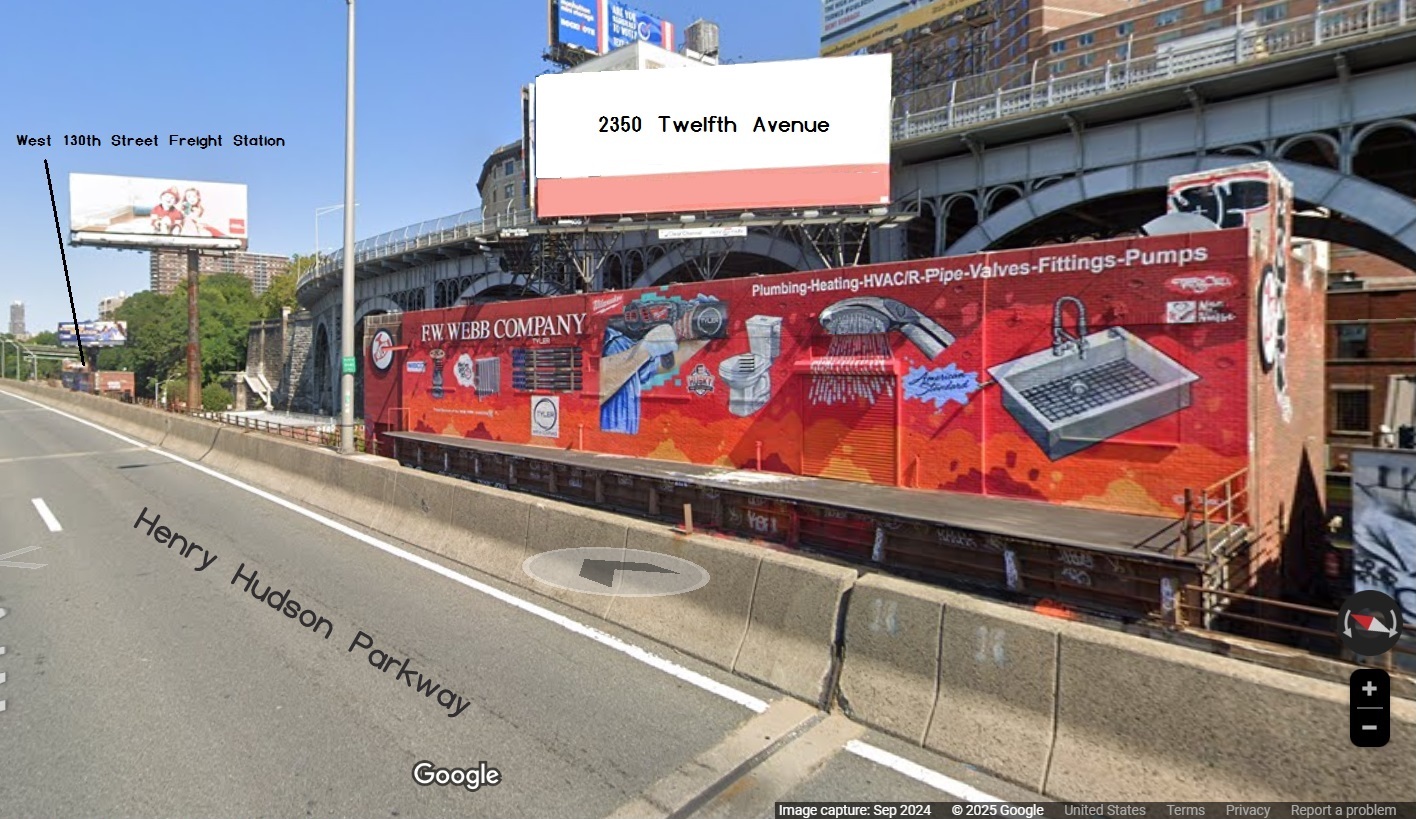

. The shoreline was landfilled as planned and greatly expanding the park area; only to be consumed by the Henry Hudson Parkway. All of this construction was completed by 1941. .  West 71st Street to Spuyten Duyvil - September 8, 1937 McLaughlin Aerial Service New York City Department of Parks & Recreation collection added 19 October 2025 . The railroad tunnel still exists to this day. A connection was built at West 36th Street to Penn Station in 1986; however the trackage would remain unused by any railroad for several more years. As a result, the tunnel become a home to itinerant homeless persons; as well as graffiti artists who used the large walls as canvases and paint some rather nice murals. At this point the tunnel took on the name "Freedom Tunnel". On April 7, 1991; Amtrak shifted its long distance and regional service from Grand Central Terminal trains to Penn Station. This would include the following services: "Adirondack", "Berkshire Flyer", "Empire Service", "Ethan Allen Express", "Lake Shore Limited" and "Maple Leaf". The homeless persons living in the tunnel were forced out (some managed to keep this their home and remain until 1994), at which time the last "official" tenant left, but it is still used covertly by the homeless.  West Side Tunnel - 2015 Will Ellis photo added 19 October 2025 . |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| location | milepost* | facilities | |||||||

| Inwood (Dyckman Street) | .98 | Freight Station | Passenger | ||||||

| Fort Washington | 2.58 | Depot | Passenger | ||||||

| West 152nd Street | 3.75 | Yard | Foundry Yard | Passenger | |||||

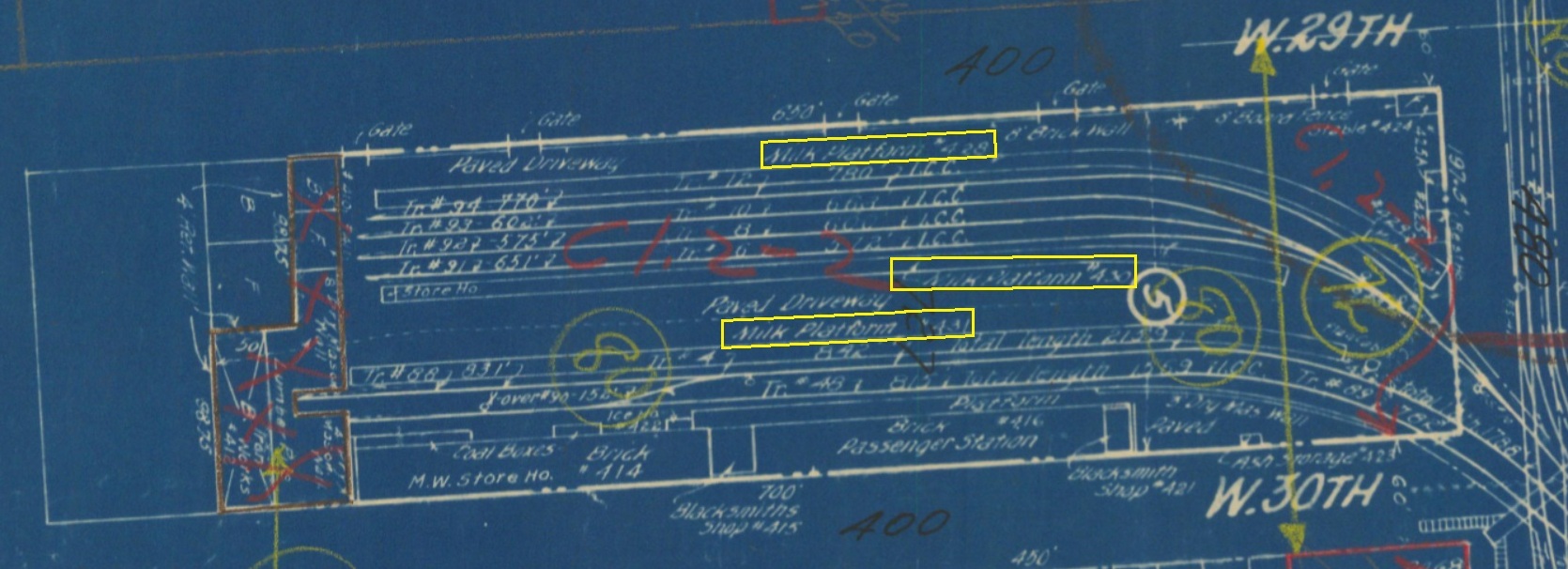

| West 148th - 143 Streets | 4.00 | Freight Station | Yard | Milk Platforms | |||||

| West 130th Street - "Manhattanville" | 4.82 | Meat Packer | Passenger | ||||||

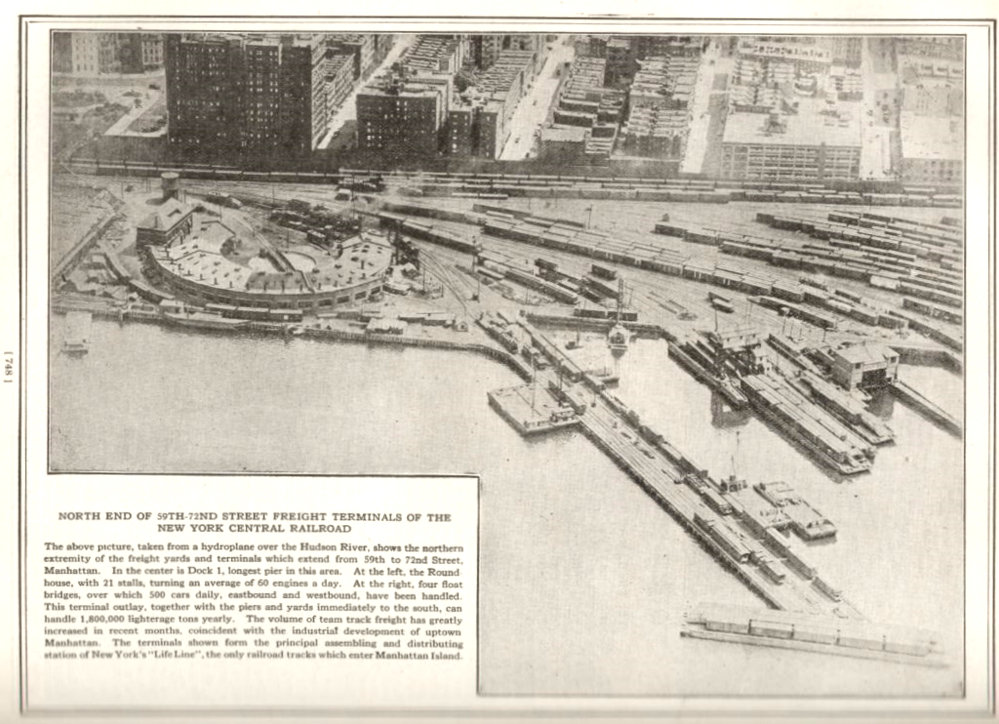

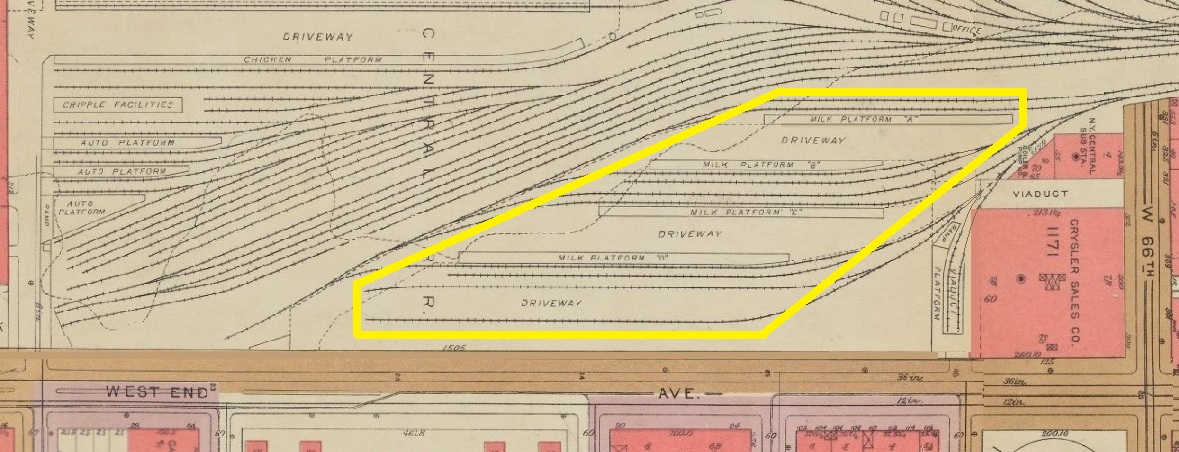

| West 72nd - 60th Streets | 8.40 | Freight Station | Yard | Stock Yard | Milk Platforms | Grain Elevators | Transfer Bridges (4) | ||

| West 59st Street | 8.50 | Freight Station | |||||||

| West 41st Street | 9.45 | Stock Yard & Slaughterhouses | |||||||

| West 36th Street | 9.70 | Freight Station | Yard | ||||||

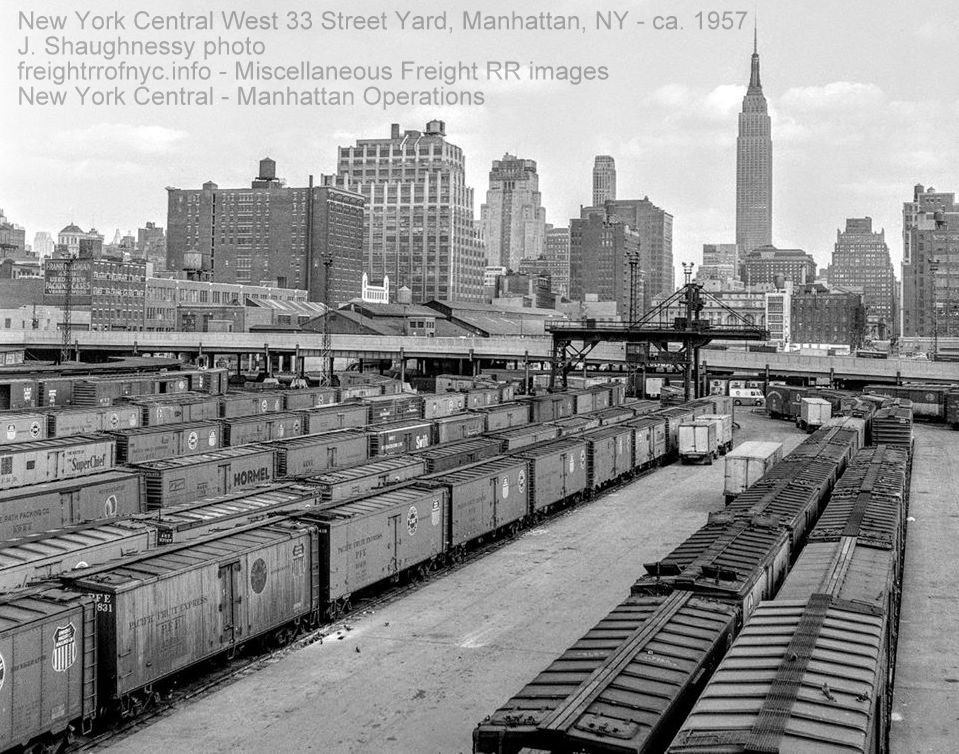

| West 33rd Street | 9.79 | Freight Station | Yard | Transfer Bridges (2) | |||||

| West 30th Street | 10.06 | Yard | Milk Platforms | Passenger | |||||

| West 17th Street | 10.62 | Fresh Produce Yard | |||||||

| St. Johns Park Terminal | 12.39 | Freight Station | |||||||

| * from Spuyten Duyvil | |||||||||

|

|

| Google Street View- looking northeast | Google Aerial View |

.

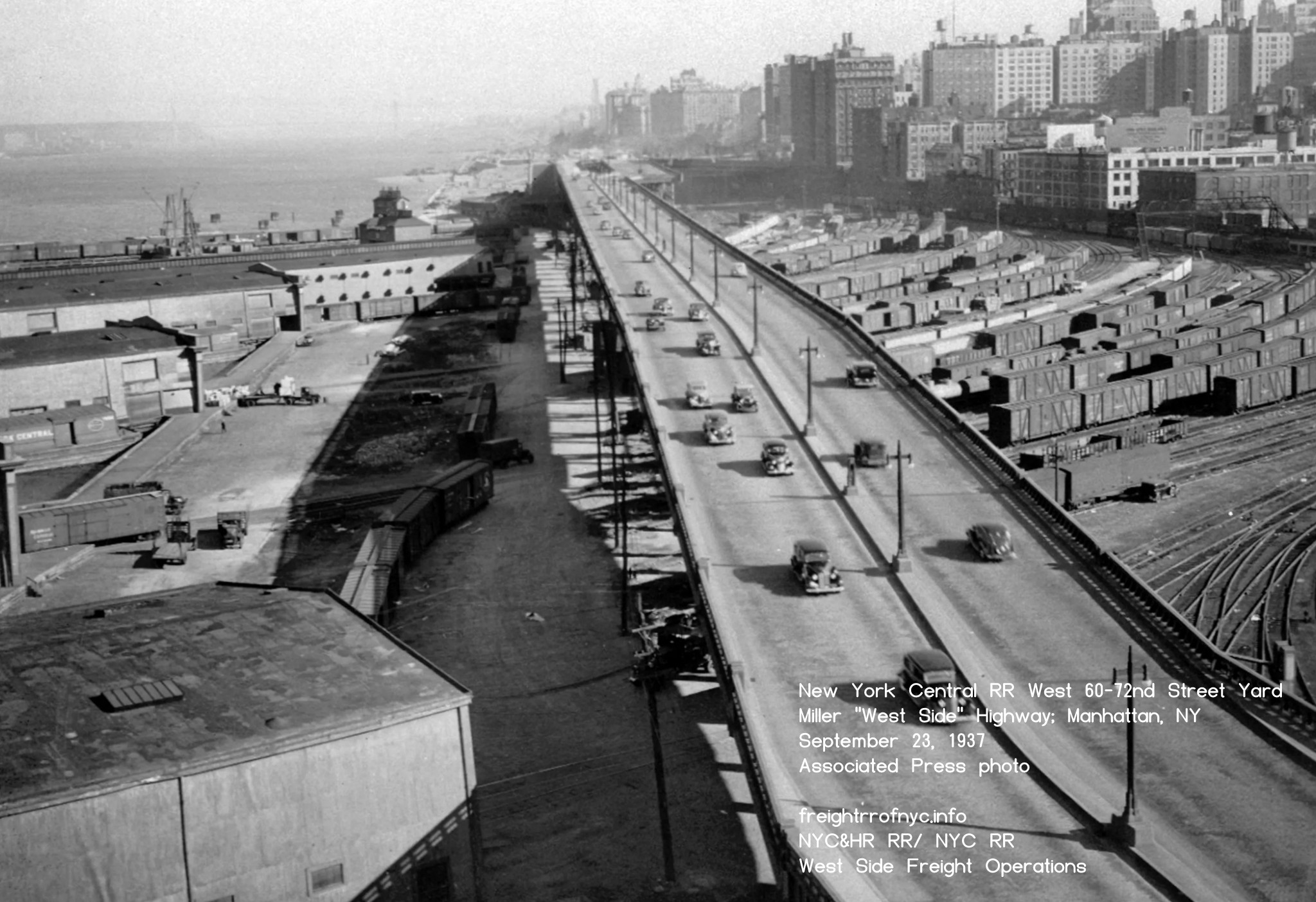

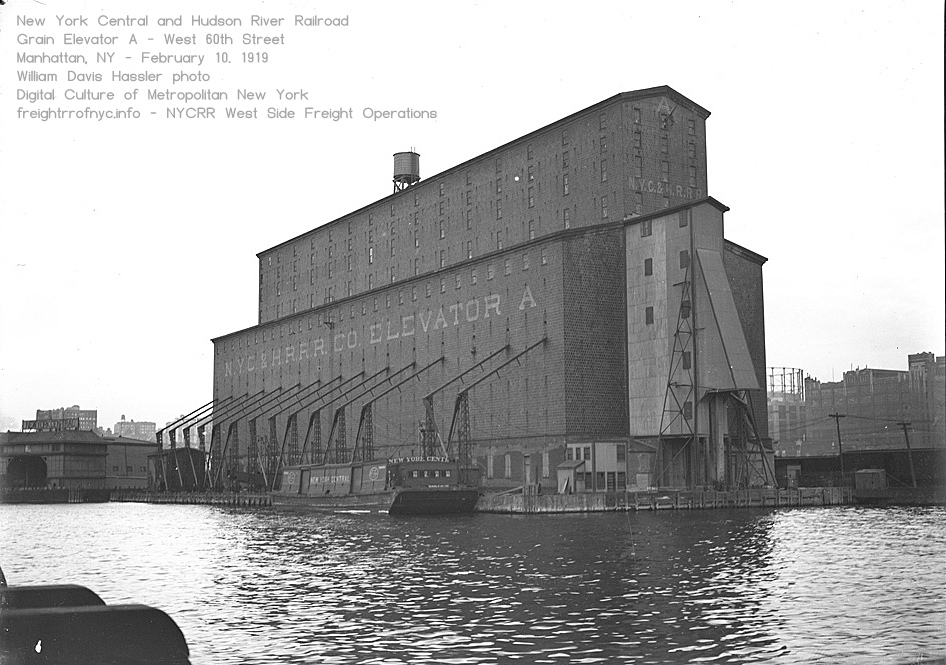

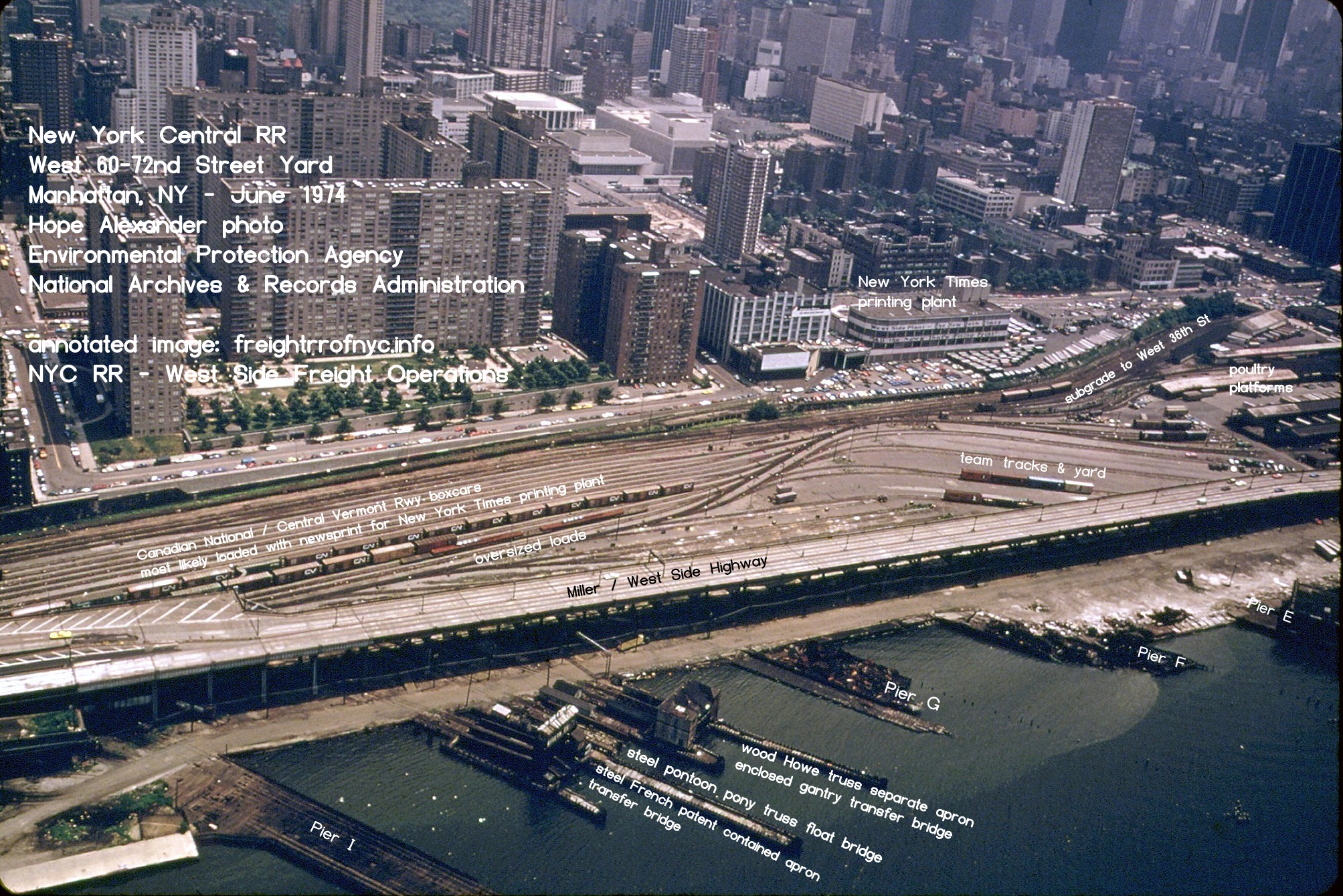

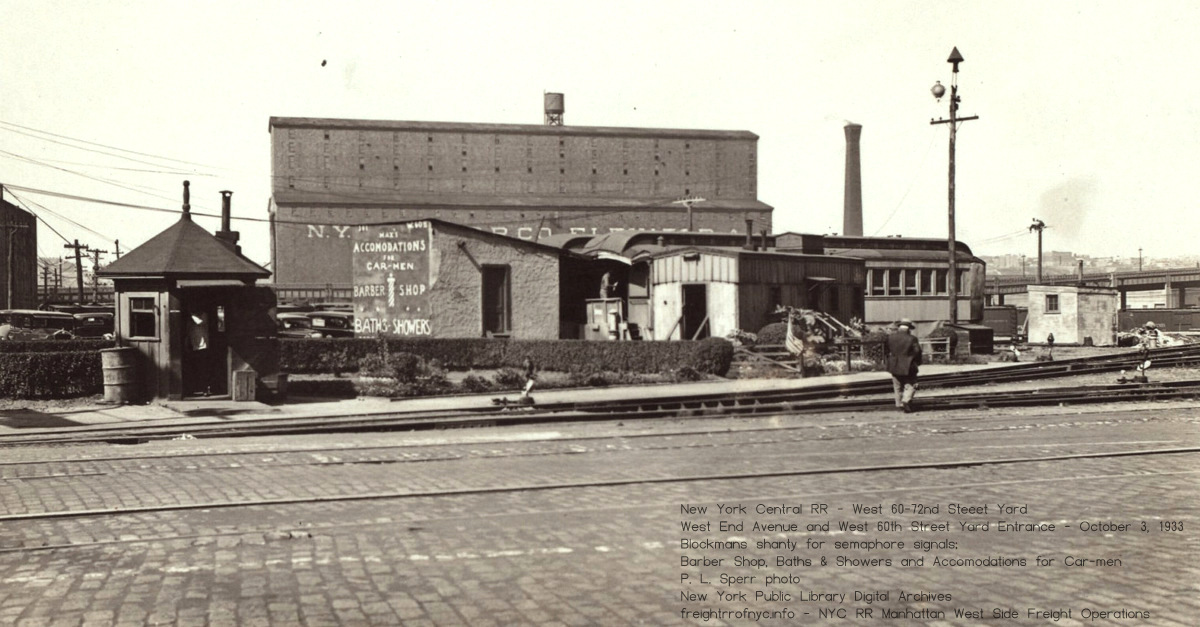

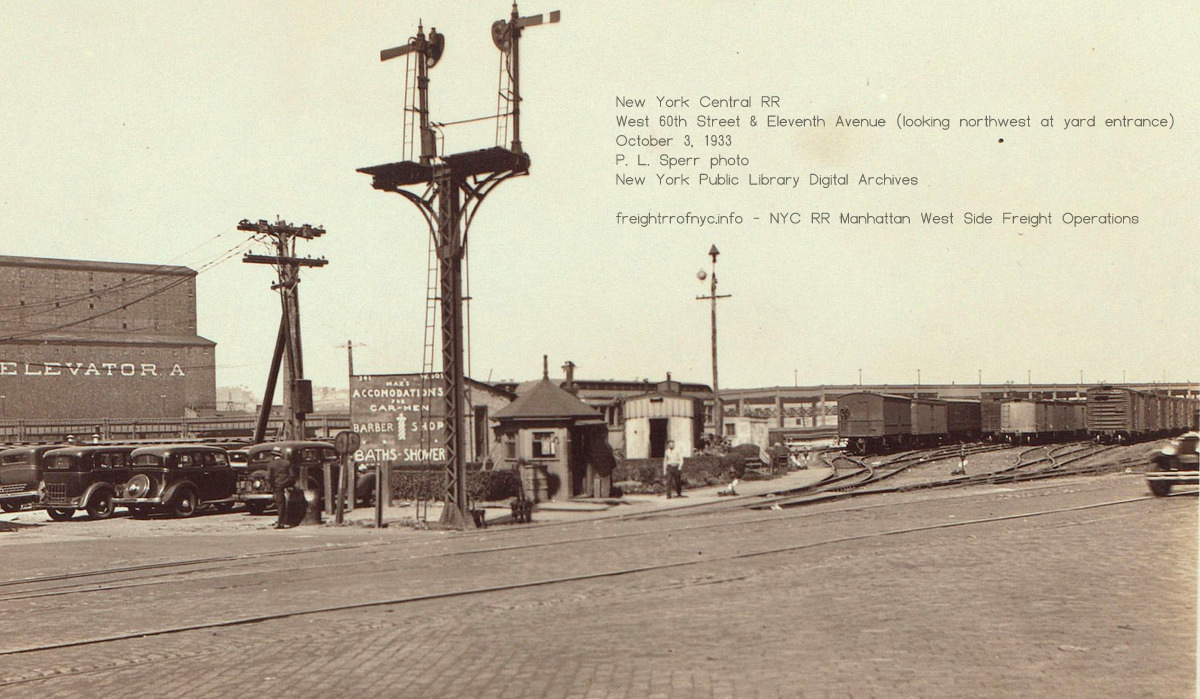

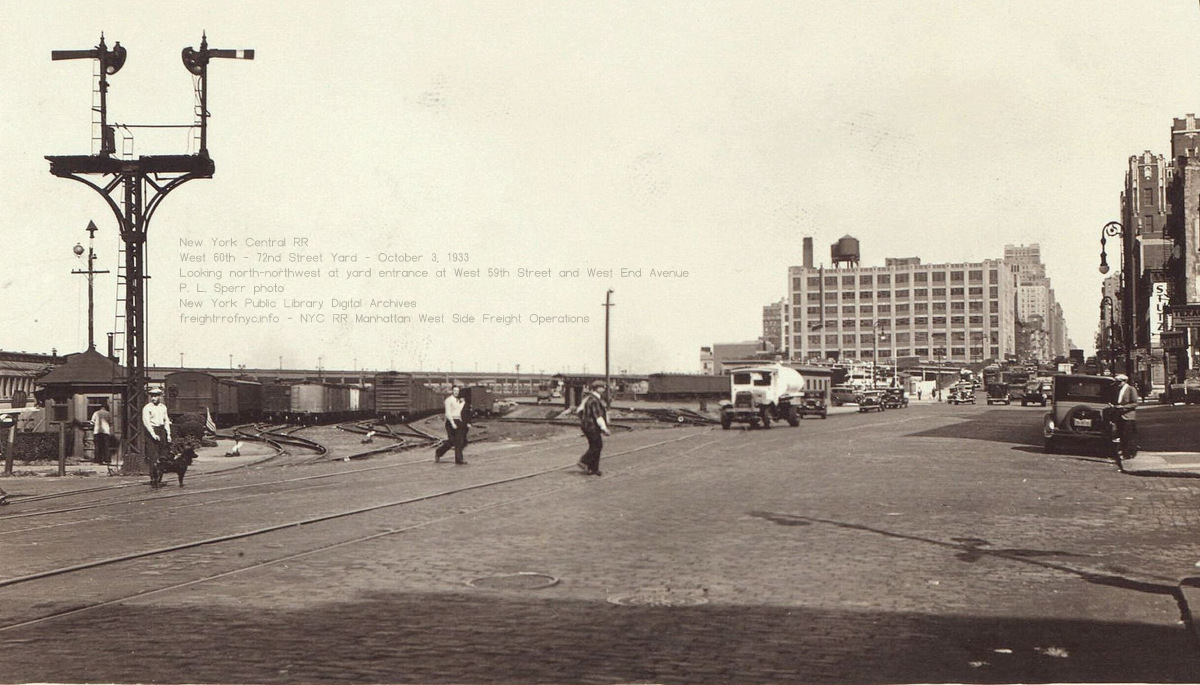

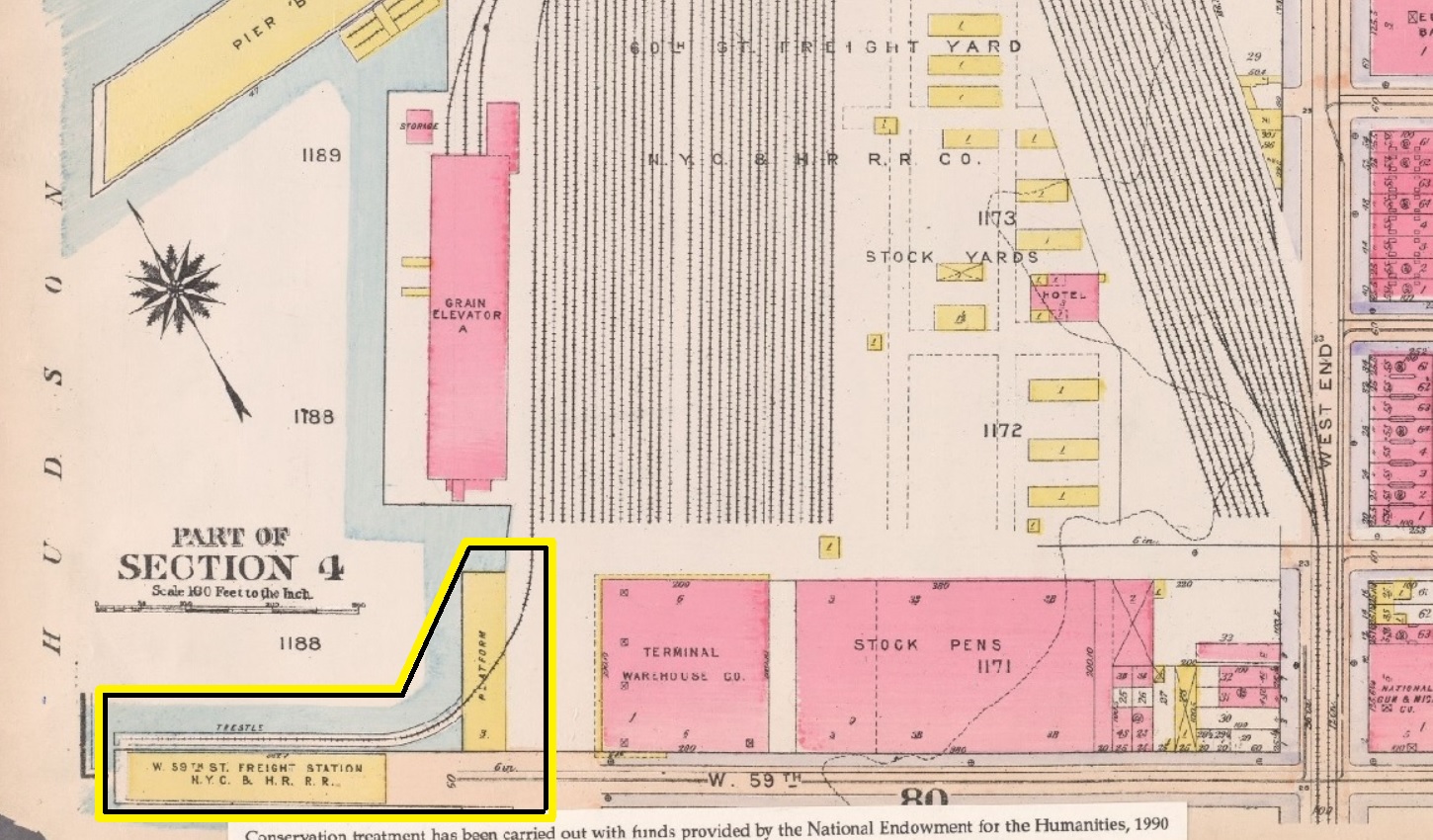

This facility's main features was comprised of the following, beginning at the northwest corner of the property at where West 72nd Street would meet the water, a rather large roundhouse and engine servicing facilities for locomotives and the Railroad YMCA and other building containing offices for railroad departments. Working south along the bulkhead was Pier I , the three transfer bridges #4 (steel overhead suspended French contained apron type), #3 (steel truss bridge on pontoon), #2 (electrically operated, overhead suspended separate apron Bensel type), then Piers G, F, E, D and B, the West 62nd Street transfer bridge #1B (electrically operated, overhead suspended, separate apron Bensel type), then Grain Elevator A between West 62nd and West 60th Streets. Just south of the grain elevator was the West 59th Street Freight Station on Pier 99. Working counterclockwise along West 60th Street were a warehouse and stock pens for cattle. At West End Avenue and West 60th Street were the yard offices and comfort station and rooms for railroad car men. In the center of all this were the stock yards, surrounded by the various classification tracks for inbound and outbound freight, and storage sidings.

Over the ensuing decades, additional property was acquired (triangle at northeast corner of 1955 map below), and the yard facilities were reconfigured to accommodate the changes in freight haulage. From the 1800's to around 1930, the stock pens at the south end of the yard were done away with and warehouses constructed. The freight station at West 59th Street was closed and property usage ceded to the City of New York Department of Sanitation (which, ironically still occupies the site.)

By the 1940's, the bulk storage of grain was no longer necessary in the New York City area. The original Grain Elevator A, which had been built in 1876, and had a capacity of 1.5 million bushels of grain and was one of the largest single structures in New York City; burnt down in April 1889 in a huge conflagration, along with Elevator B which was located on the pier. After the fire, Elevator A was built back slightly larger somewhat combining the capacities of the two previous elevators. For those of you who are interested, a bushel of grain weighs 60 pounds. A new grain elevator built in 1941 and of 13.5 million bushel capacity was constructed at Albany, NY (130 miles north), which pretty much supplanted those in the New York City proper. The grain elevator site in Manhattan now was home to a small concrete plant built in its footprint.

The advent of mechanical refrigeration led to a decline of the local slaughterhouses, what with meat now being able to be processed closer to the stockyards of the Midwest. As such, the stock yard at West 60th Street was closed, with any remaining inbound livestock destined for West 41st Street. This space developed into the poultry area. Trackage and poultry platforms were constructed, arranged as such with a track on one side and a wide driveway on the other. Poultry cars would be spotted at these platforms, and poultry buyers would back up their trucks to the platforms to load.

Additional platforms were built to the east of the poultry area for automobile unloading, which by the 1940's was really becoming a major shipping commodity. A chicken in every pot and an automobile in every garage finally became reality!

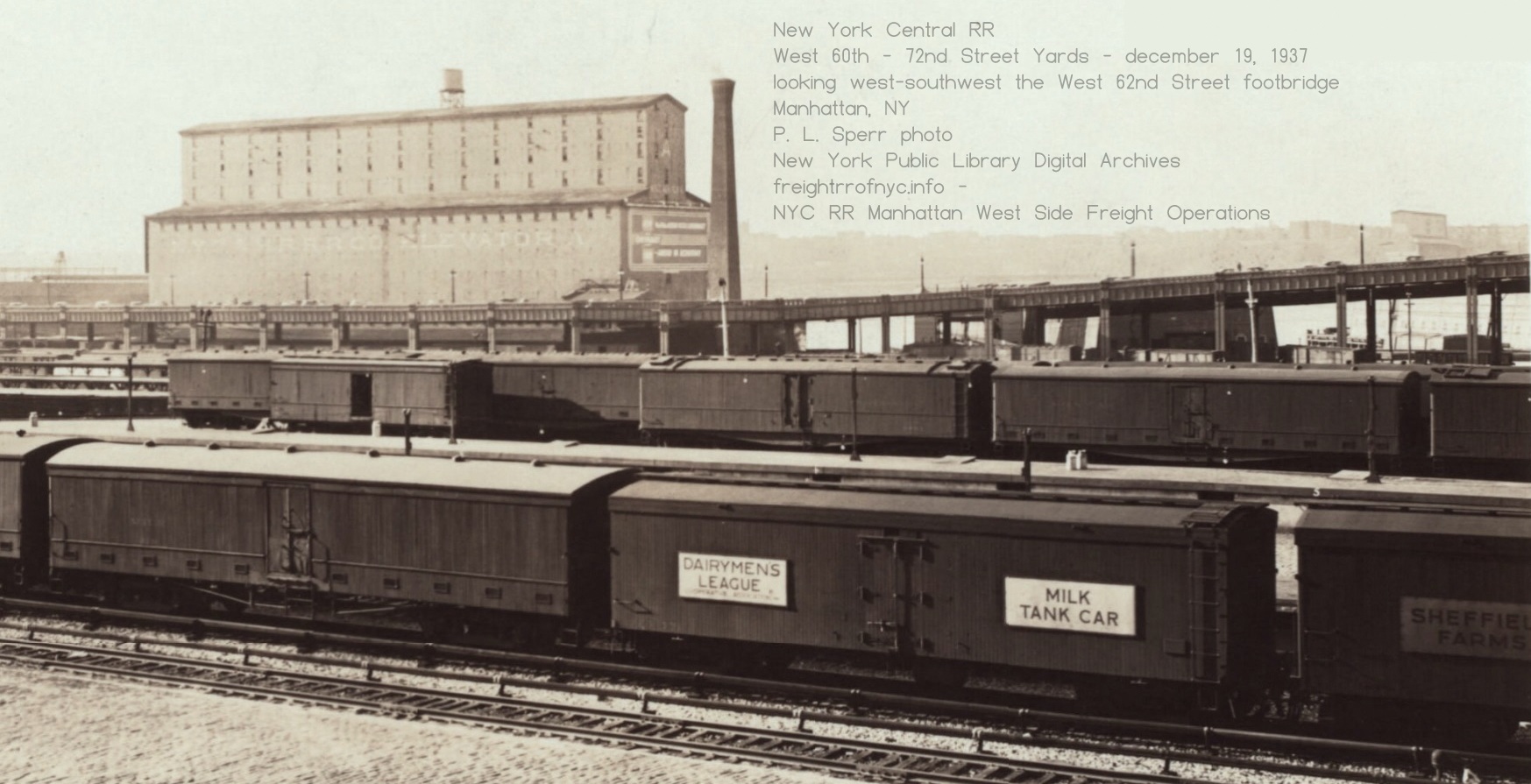

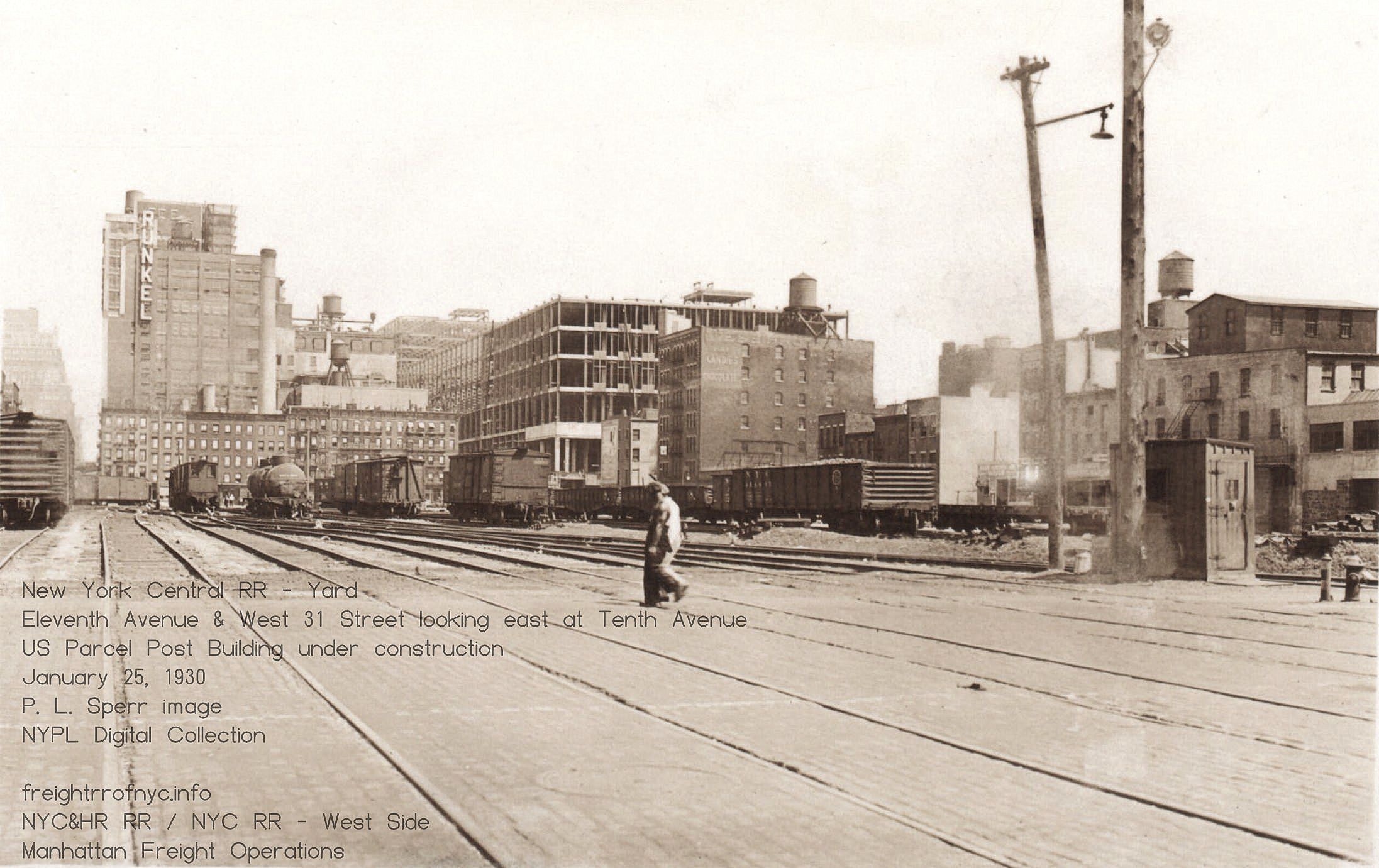

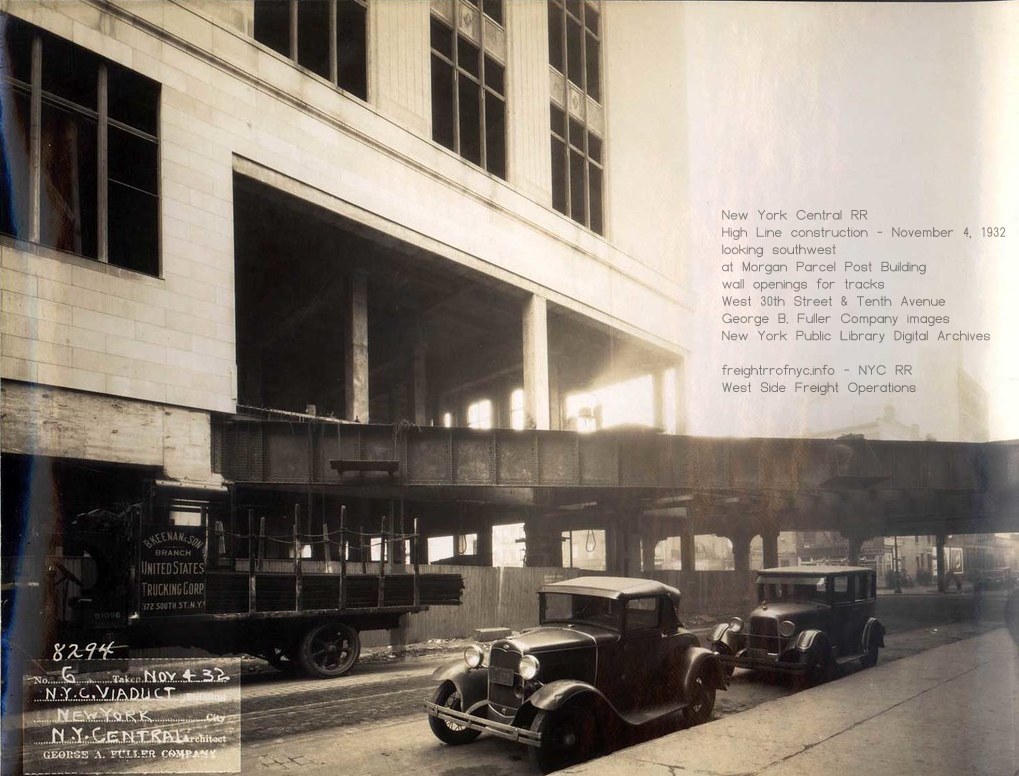

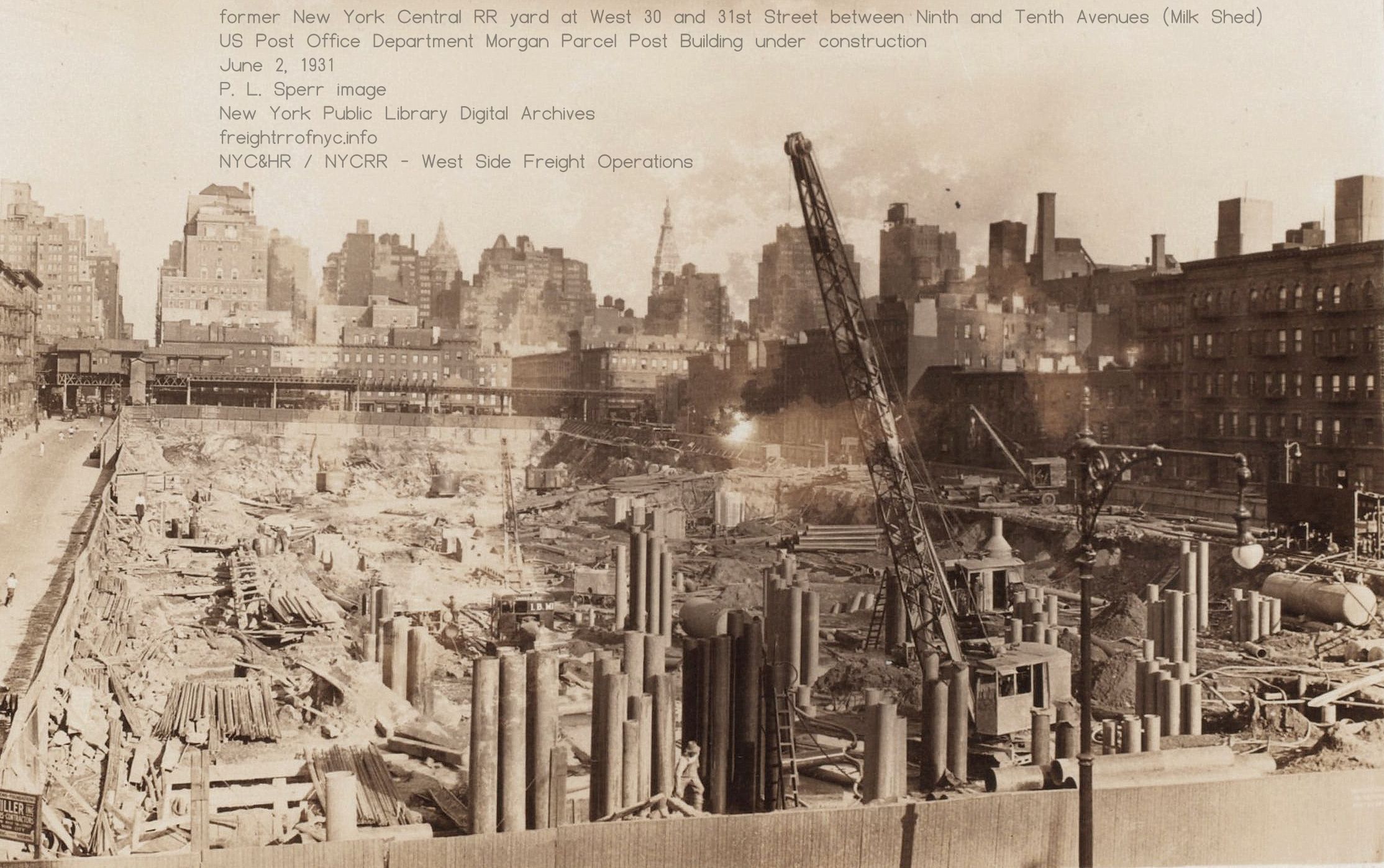

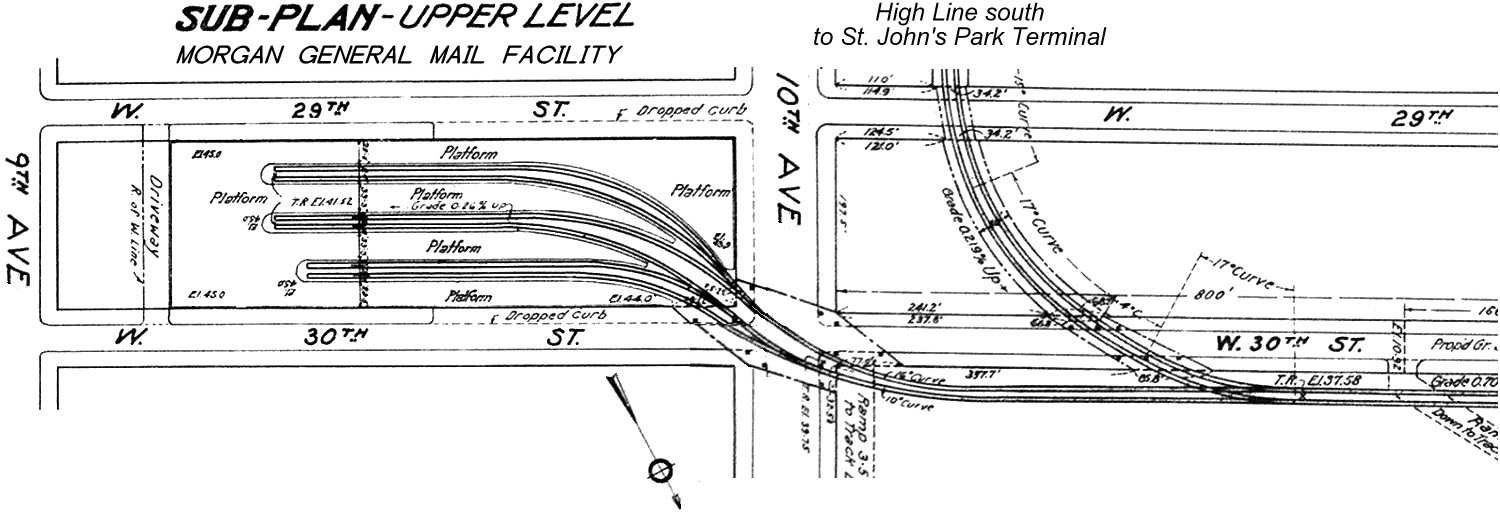

Strangely, new milk platforms were built in the in acquired triangle bordered by West 65 and West 62 along West End Avenue. These replaced the milk platforms that were located at West 30th Street between Ninth and Tenth Avenues and that were razed for construction of the Morgan Parcel Post Facility. But, with the advent of the mechanically refrigerated express milk car (tanks) these platforms would not last long.

.

Just about the time that 1955 Bromley Property Atlas was published, New York Central sold that triangle of land where the milk sheds were located to the New York Times, for an anticipated printing plant as referenced in the October 1955 issue of New York Central Headlight. This printing plant became operational in July 1959, and ceased operations in 1976 with the opening of the Carlstadt, NJ plant. This is important as we know Conrail was handling carloads of paper in 1982 at West 60th-72nd Street Yard for the New York Times, and where it has been stated trucks were transporting the rolls of newsprint from the yard in Manhattan to New Jersey.

.

.

.

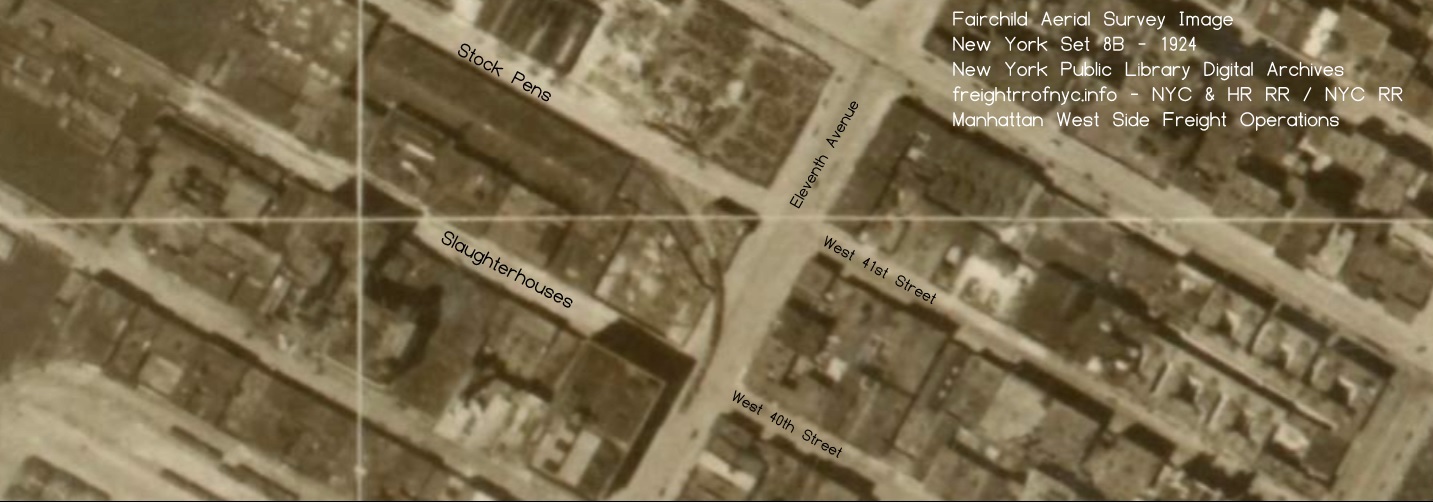

1924 - Fairchild Aerial Survey Image

8B - N.Y.C. (Aerial Set)

New York Public Library Digital Archives

annotated by author © 2025

click on map for un-annotated version

added 02 September 2025

.

. For that direct freight

that was to be transfered to New Jersey and the terminals in Brooklyn

and Queens, those cars were blocked and placed into the

transfer bridge assemblage yards, for eventual loading upon carfloat.

Carfloats (waiting to be unloaded, or those that were loaded and

waiting for pick up were moored to piling in the carfloat holding area.

Pier I: this was an open pier and was for oversize and heavy freight, such as structural beams, boilers, engines, machinery, trucks, etc; and that of which required transfer for lighterage by open barge or stick lighter for further travel to its destination.

Pier G was designated for westbound / outbound freight (to New Jersey). Cars that needed to be combined were placed in sub-yard G, until dock workers could get to them.

Pier F was designated to handle eastbound / inbound (to Manhattan) barreled flour. Cars that needed to be loaded with this barreled flour were stored in sub-yard F.

Pier E was designated for dry export.

Pier D was designated for miscellaneous freight.

"Pier C" is mentioned in Gratz Mordechai's "Report on Terminal Facilities for Handling Freight of the Railroads Entering the Port of New York" as being held in reserve and not used frequently. This is odd, because there is no Pier C shown on any of the maps, property or railroad. It may have burned in the April 1889 conflagration, discussed below.Elevator B is also mentioned in Mordechai's "Report on Terminal Facilities"; but it too is not shown on any maps. It is believed at this time, it occupied "Pier B" as Elevator B had direct waterside transfer. Located in an 1889 Report of the Fire Department of the City of New York; a lard factory located at West 59th Street and Twelfth Avenue caught fire on April 19 at 3:40 pm. The building was fully engulfed within minutes; and the heat thereof communicated to surrounding structures which included Elevator A, and Elevator B, even pierhouse Pier D. The New York Times coverage "Millions Swept Away" and of this conflagration gives explicit details. When an urban area like New York (or Chicago or San Francisco) had a fire, it really knew how to have a fire! As Elevator B was built on a pier so fire apparatus could not access it despite fireboats being on scene. So it appears Elevator B was not rebuilt following this fire, and the pier reconstructed as a pier house instead. Elevator A however, was rebuilt. This also explains the construction date of 1889 for Elevator A.

Elevator A was used for the storage of grains with 2,300,000 bushel capacity. Carloads of grain and corn both for human consumption as well as those used for livestock needs. Cars went to Elevator A yard to be brought into one of three tracks underneath the elevator for transfer by conveyor into the appropriate silo bin. If I understand what I read correctly, it was supposedly regulated that a 10 days worth supply of grains needed to be kept on hand. As it was dispensed into either covered barges or floating grain elevators for further distribution.

West 60th Street Stock Yard: for livestock that was not destined for West 41st Street Livestock Yard and Abbatoirs (slaughterhouses); these were placed into the West 60th Street Stock Yard unloading tracks. The stock house (building) that was located on West 60th Street, was known as the "sheep house."

Team tracks: Team tracks at this facility were an unusual departure from the standard arrangement. The more common arrangement was to have one or two tracks with wide driveways on either side paralleling the trackage; then another track or two, a wide driveway, another track or two; and so on. This allowed a horsedrawn wagon or cart, or truck, that could either back up directly to the boxcar door or park alongside it for loading and unloading. However, here at West 60th Street Yard, a single team track came out from each of the pier house leads (or the transfer bridge lead) and curved to run parallel along the bulkhead and alongside a raised platform which was located between the track and the bulkhead; and parallel to the long driveway; but this track now ran perpendicular to the sub-yards trackage themselves. Freight could be directly unloaded from a barge or lighter moored to the bulkhead and directly into a freight car, or the freight car could be unloaded to the platform or onto a barge or lighter. After unloading, the car went to the empties yard. Freight could be anything from one or two crates, to crated appliances, furniture. Team tracks are highlighted below in yellow (north is to the right):

Empties Yard: empty cars went to the "empties yard" where they would be cleaned and swept out, if required. This task was usually relegated to male pre-teen and teen aged youth. These were the days where there were no under age employment laws. After cleaning, empty cars would be brought to whatever pier shed that needed cars for loading on an as need basis. This freight would arrive by covered barge or lighter; and whereas these loaded cars were then made up into outbound (northbound) trains.

Car repair tracks: adjacent to the empties yard. Here carpenters, metal workers, and any other skill craft that was necessary for the repair of freight cars was located here. These repairs could be as simple as replacing a broken or bent hinge on a door; to an entire wood body or floor; or later metal patches to steel cars.

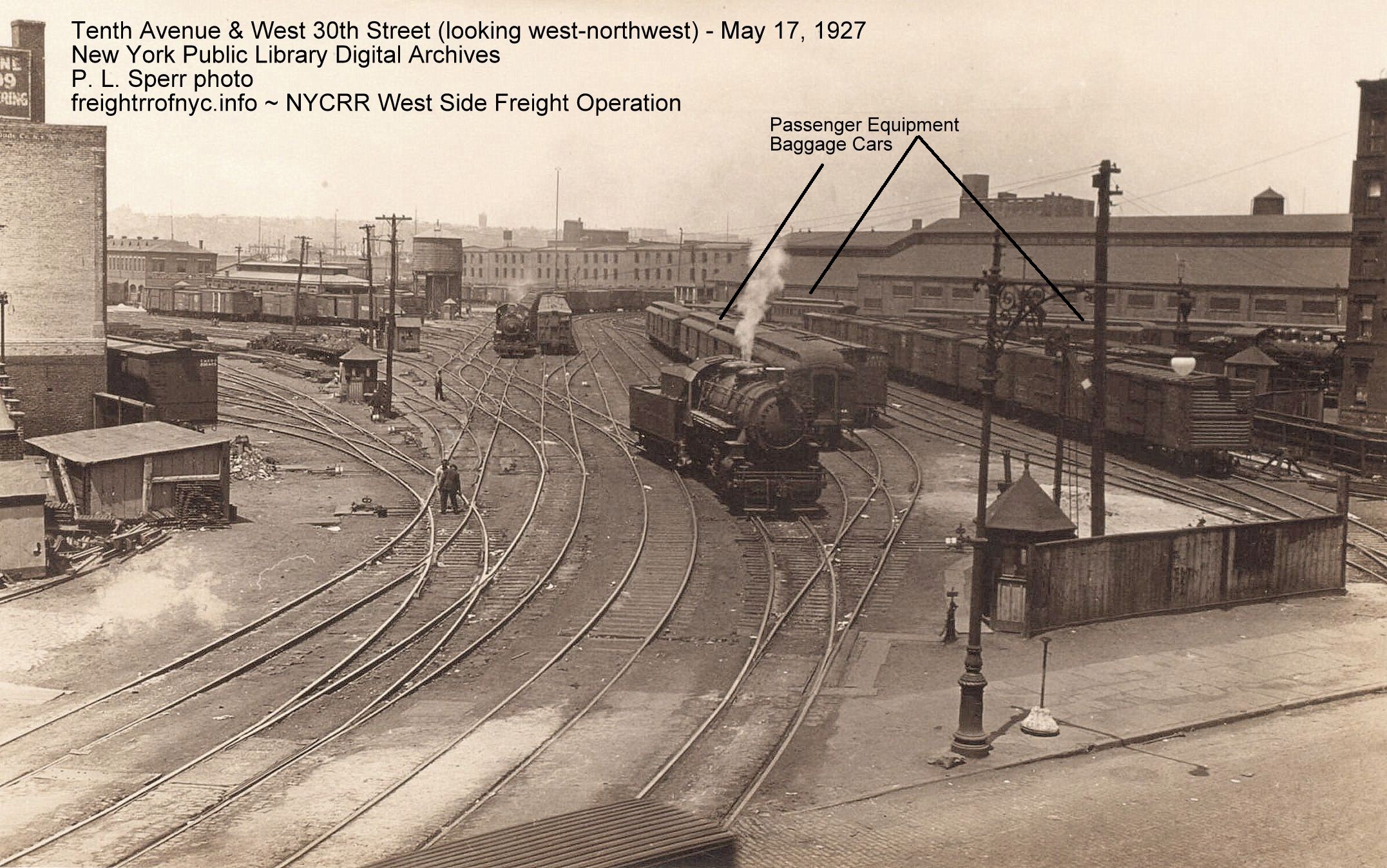

The train assembly yard was for putting together the various groups of cars for the terminal yards and freight houses further south. Those long distance trains that arrived, were broken up (or broken down, depending on your preferred railroad lingo) by switch engines. Cars for the same general locations were grouped together (or "blocked" in railroad parlance). For those cars to be forwarded to the West 36-30th Street Yards and Freight Houses, and New Washington Square Market and St. John's Terminal, were made up in smaller blocks of cars, usually no more than 8 to 10 cars which was the norm for street running in Manhattan.This could include, but are not limited to:

- the New York Stock Company's Stock Yard and the Abbatoirs (slaughterhouses) at West 41st Street;

- carload and less than carload freight to West 36th-33rd Street Yards;

- Milk trains were "unit trains" meaning the entire train was comprised of milk cars. These milk cars went to the milk platforms at West 29th Street, or after 1930; to the platforms built at West 62nd Street and Eleventh Avenue to replace the West 29th Street milk platforms which were razed for the Morgan Parcel Post Building. Most milk cars had white roofs to reflect heat from the sun.

- the Fresh Produce Yard at West 17th Street;

- the New West Washington Market, at West Street at the foot of Gansevoort Street;

- spurs into the pierhouses of South Pacific Steamship Company occupying Piers 48, 49 and 50; located at the foot of West 11th Street, Bank and Bethune Streets respectively.

- the St John's Park Freight Terminal.

Running tracks were kept clear for the passage of trains.

In

short, the West 60th-72nd Street Yards were the "heart" of the New York Central Railroad's Manhattan

freight operation. From here, it went out to peripheral routes; the "arms

and legs" of commerce.

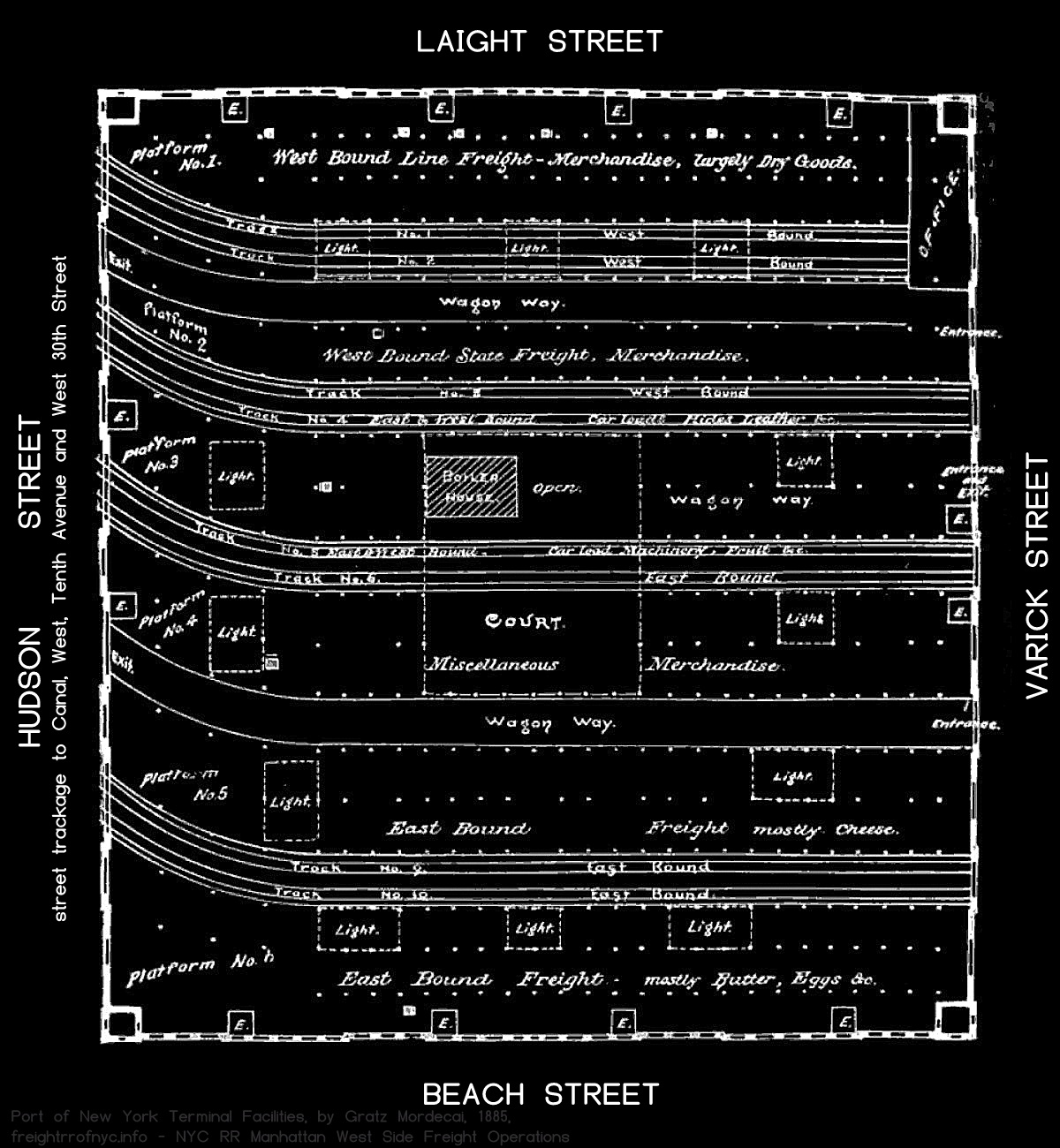

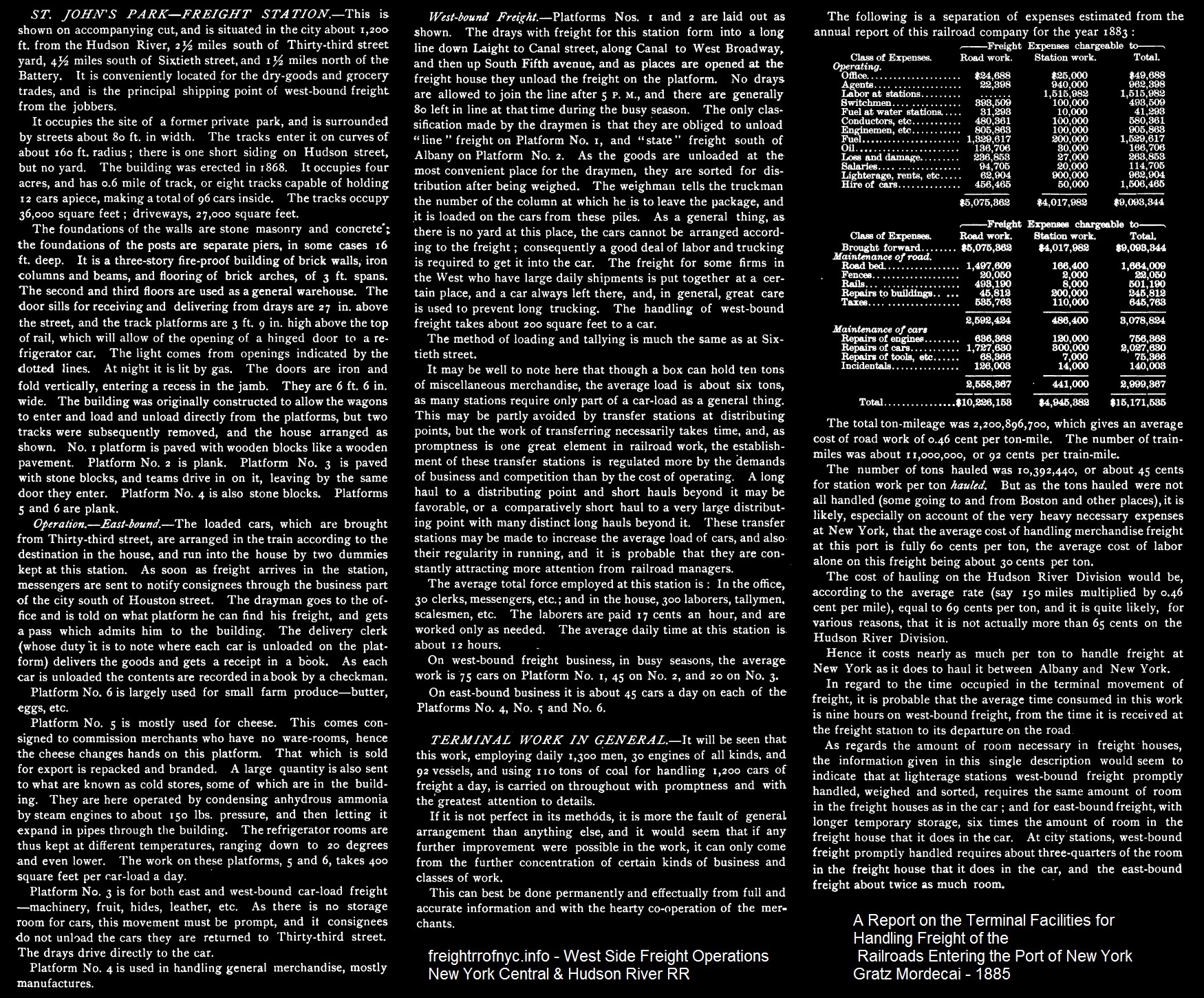

Excerpts of physical characteristics of New York Central terminals are

included

below; but perhaps most importantly, the procedures on how the freight

was handled at each of the terminals is defined in great detail.

Therefore, I have simply reproduced the text here verbatim. Keep in

mind, this is how the freight was handled and the terminals operated in

1885 - and such procedures likely changed over the decades.

1921 New York Central Railroad Industrial Directory and Shippers Guide - Page 748

image courtesy of Terry Link - canadiansouthern.com

the unabridged directory is available on Google Books and the section pertaining to New York City are pages 746 through 762

added 15 August 2025

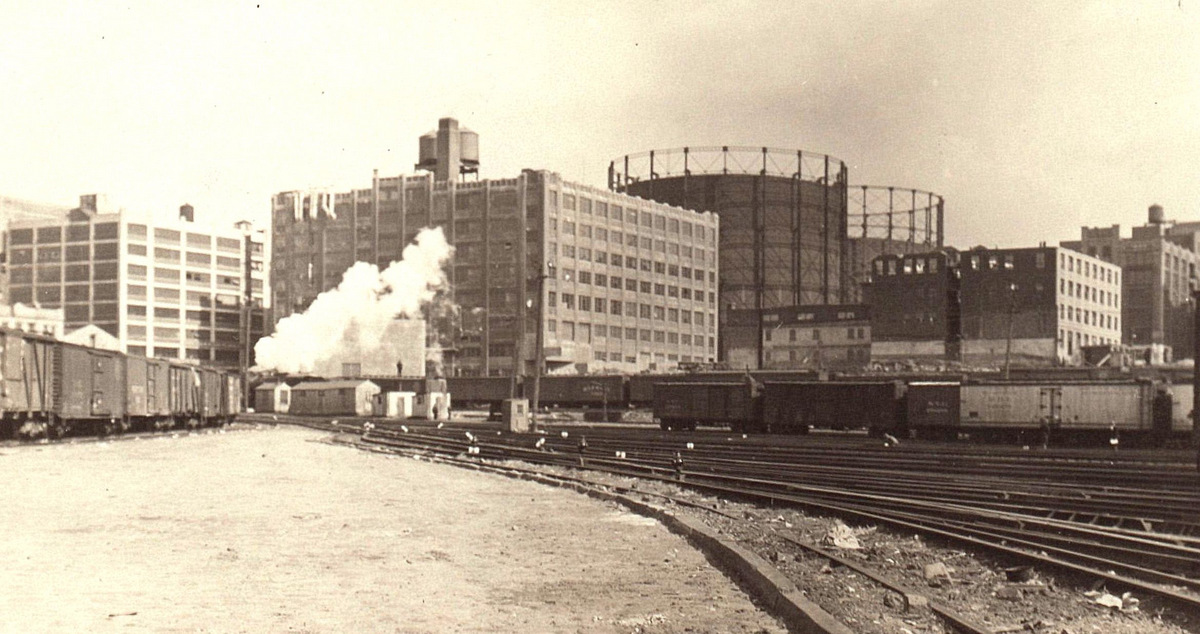

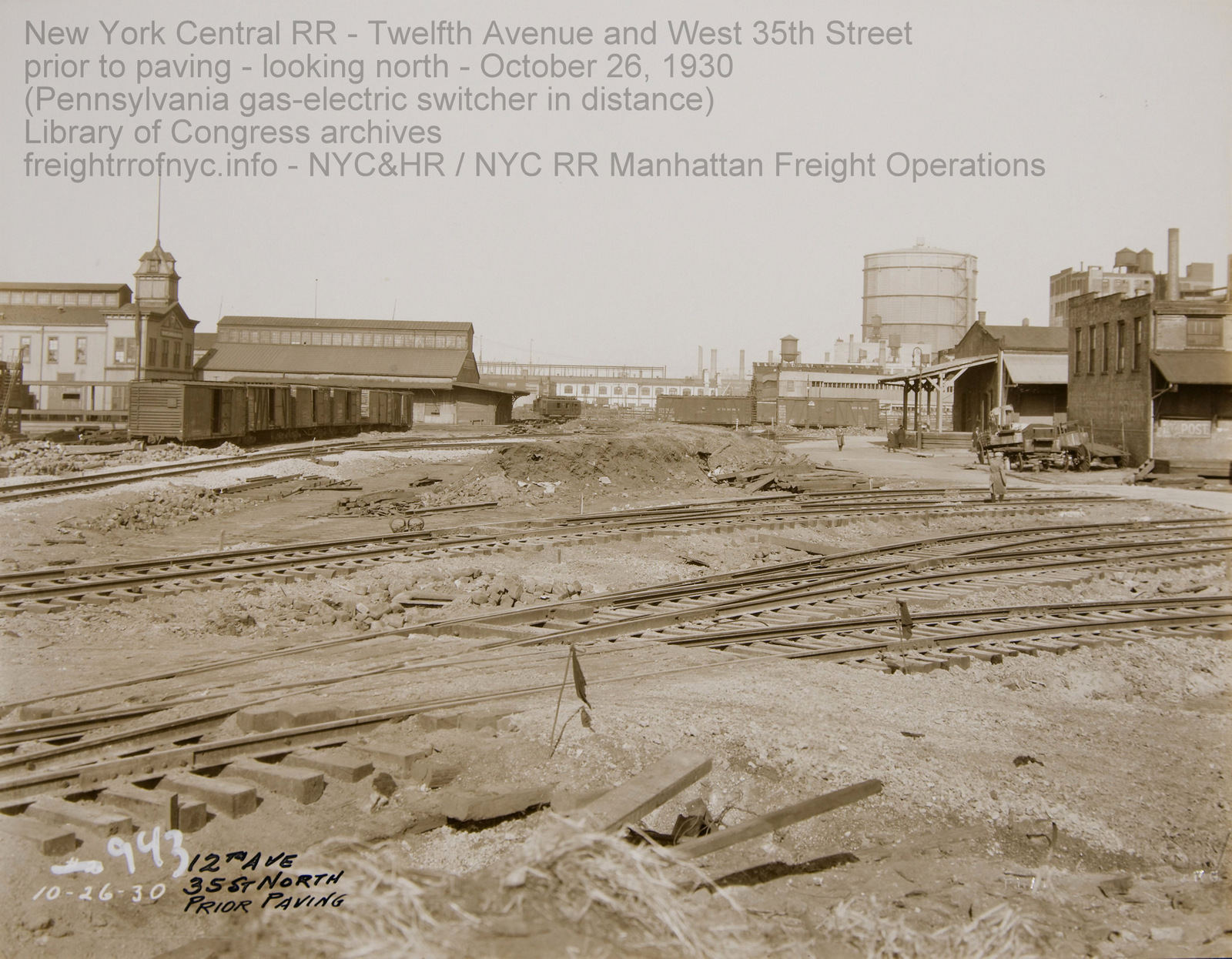

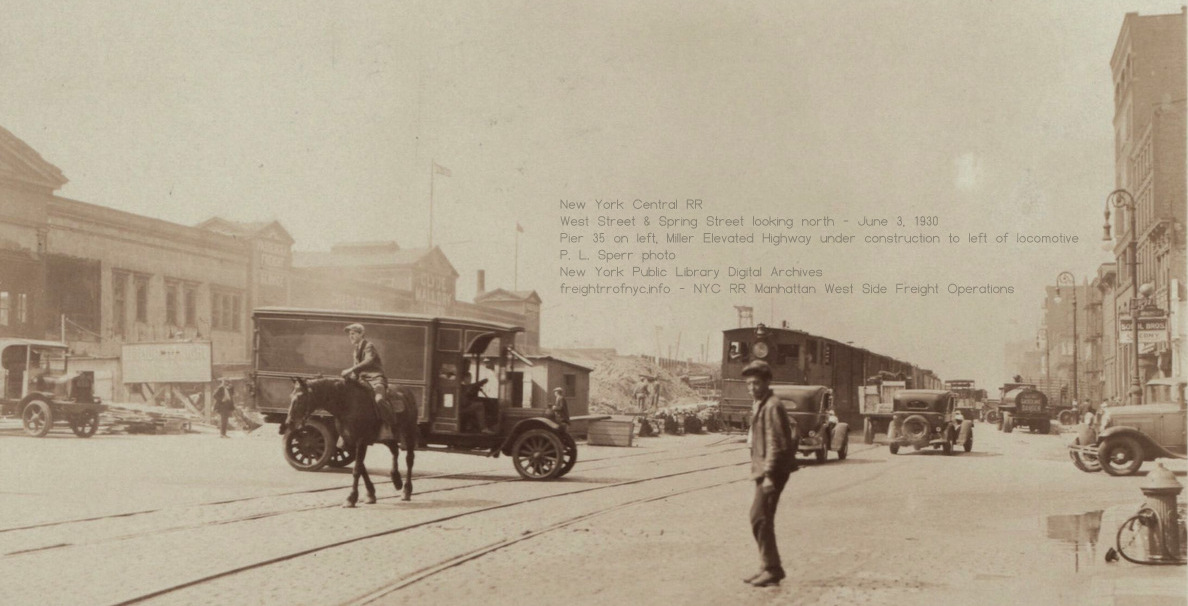

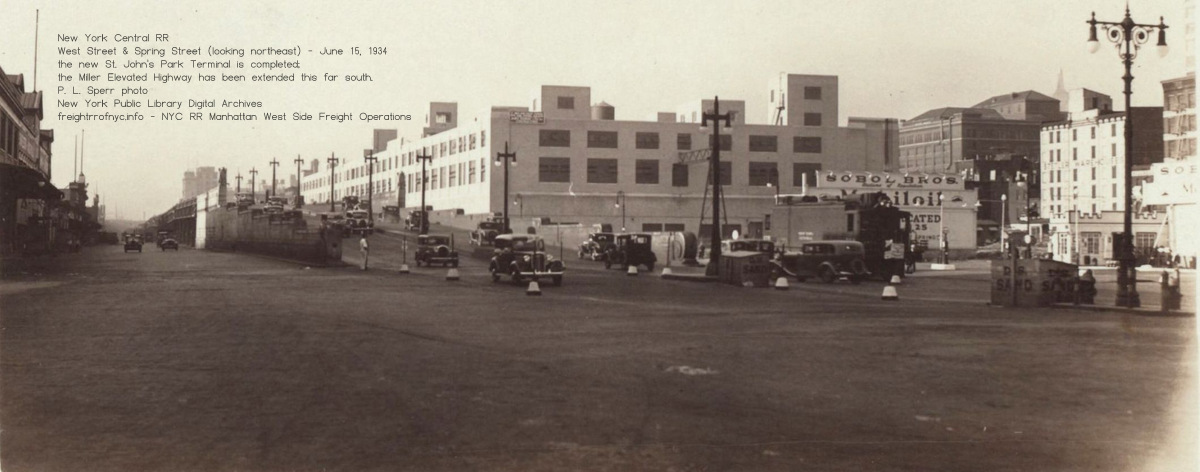

Some of the following images were taken as part of a series

for surveying the route and subsequent construction of the Miller Elevated Highway a/k/a West Side Highway.

Because of the vastness of this facility, I have made an

attempt to separate images into geographical groupings. This set of

images view the structures and yards from the west side.

.

T. Flagg photoleft: electrically operated, overhead suspension; steel, contained apron bridge "J. B. French patent" with steel gantry

center: pontoon float / steel, pony truss

right: electrically operated, overhead suspension, wood, Howe truss bridge / separate Apron "J. A. Bensel patent" with wood enclosed gantry house

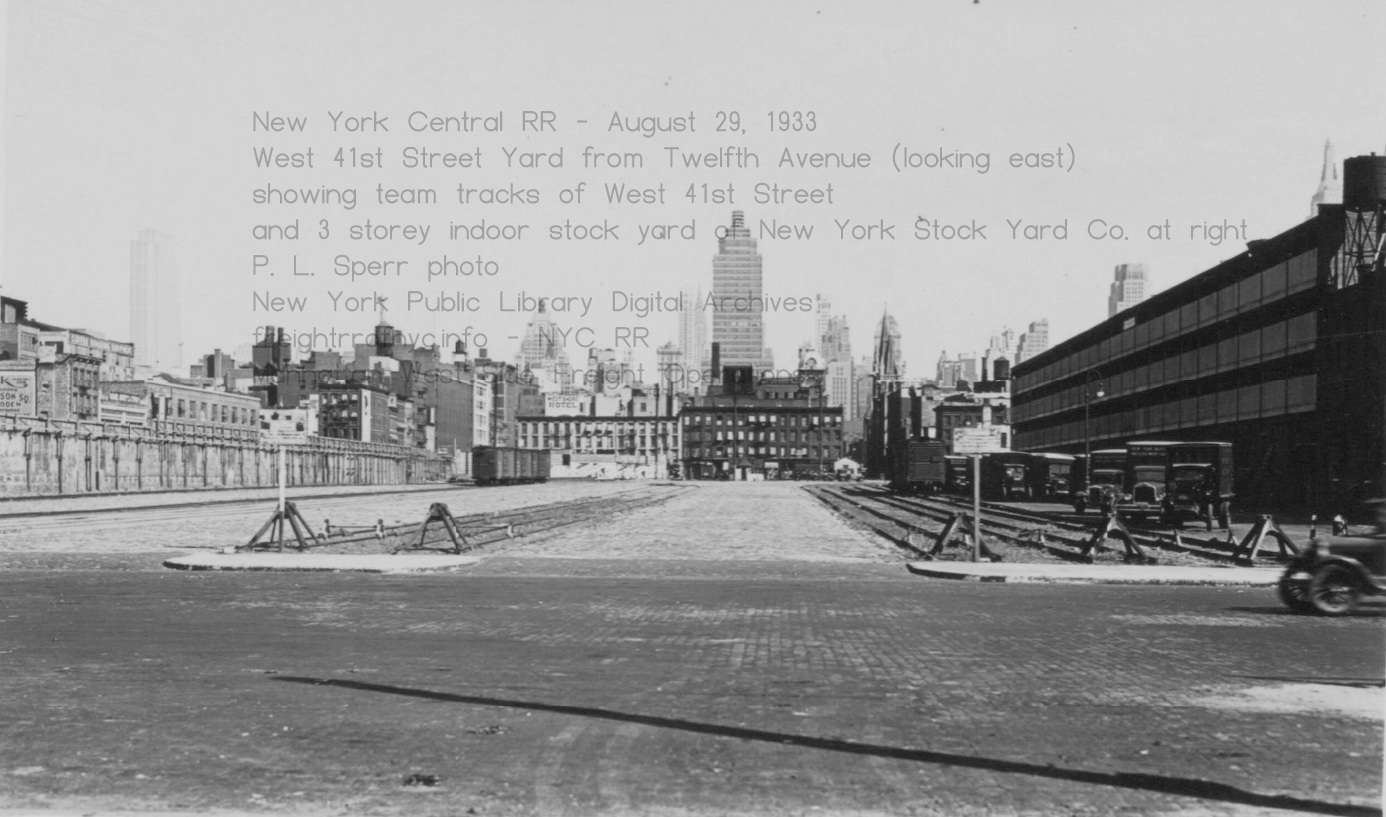

West 41st and West 42nd Street between Eleventh and Twelfth Avenues - December 1932

Looking west-northwest. Christmas trees! This was the stock yard for Abbatoir Row, out of view to the left.

New York Public Library

P.L. Sperr photo

added 19 August 2025

.

.

West

41st Street / West 40th Street / West 39th Street - Stock Pens and "Abbatoir Row"

Fairchild Aerial Survey Images - 1924

New York Public Library Digital Archives

added 19 August 2025

.

.

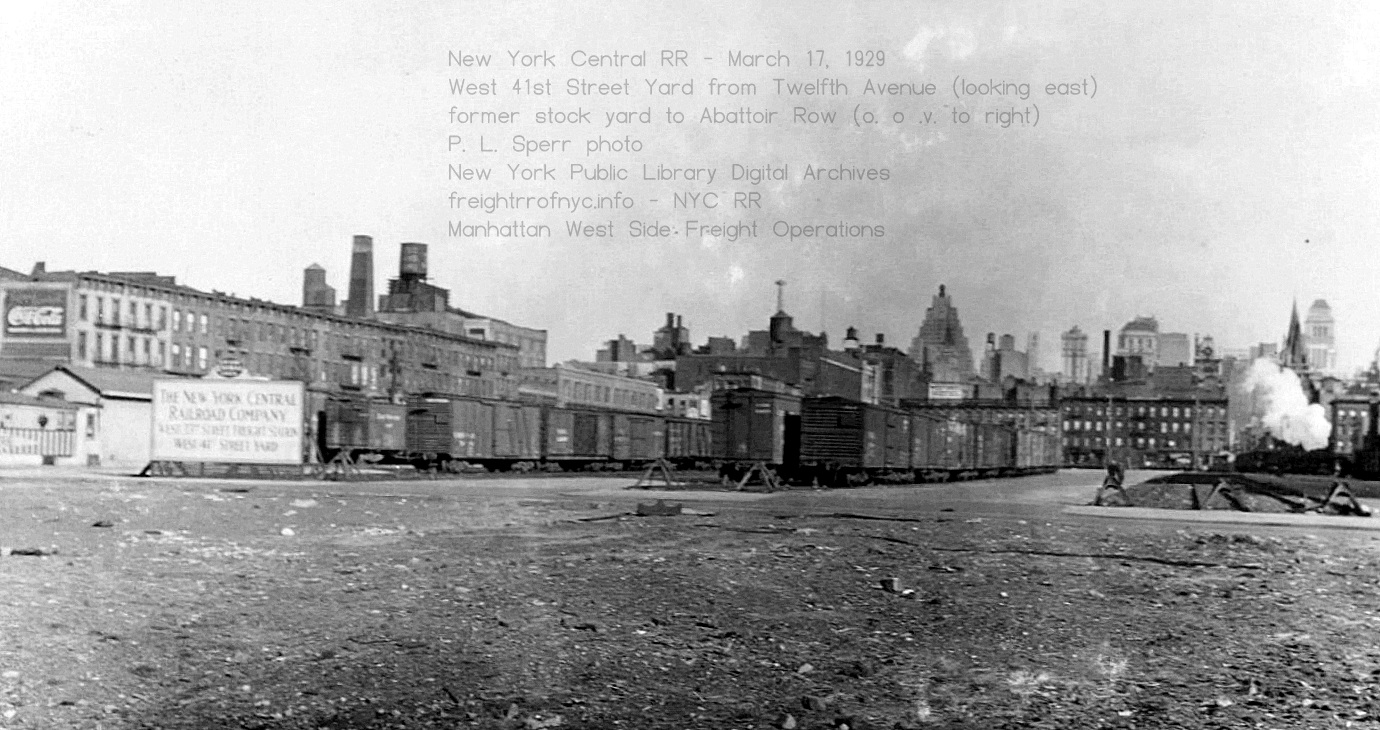

West 41st

Street Yard looking east from Twelfth Avenue. Former stock yard for

Abbatoir Row out of view to right (south) - March 17, 1929

P. L. Sperr photo

New York Public Library Digital Archives

added 28 August 2025

.

.

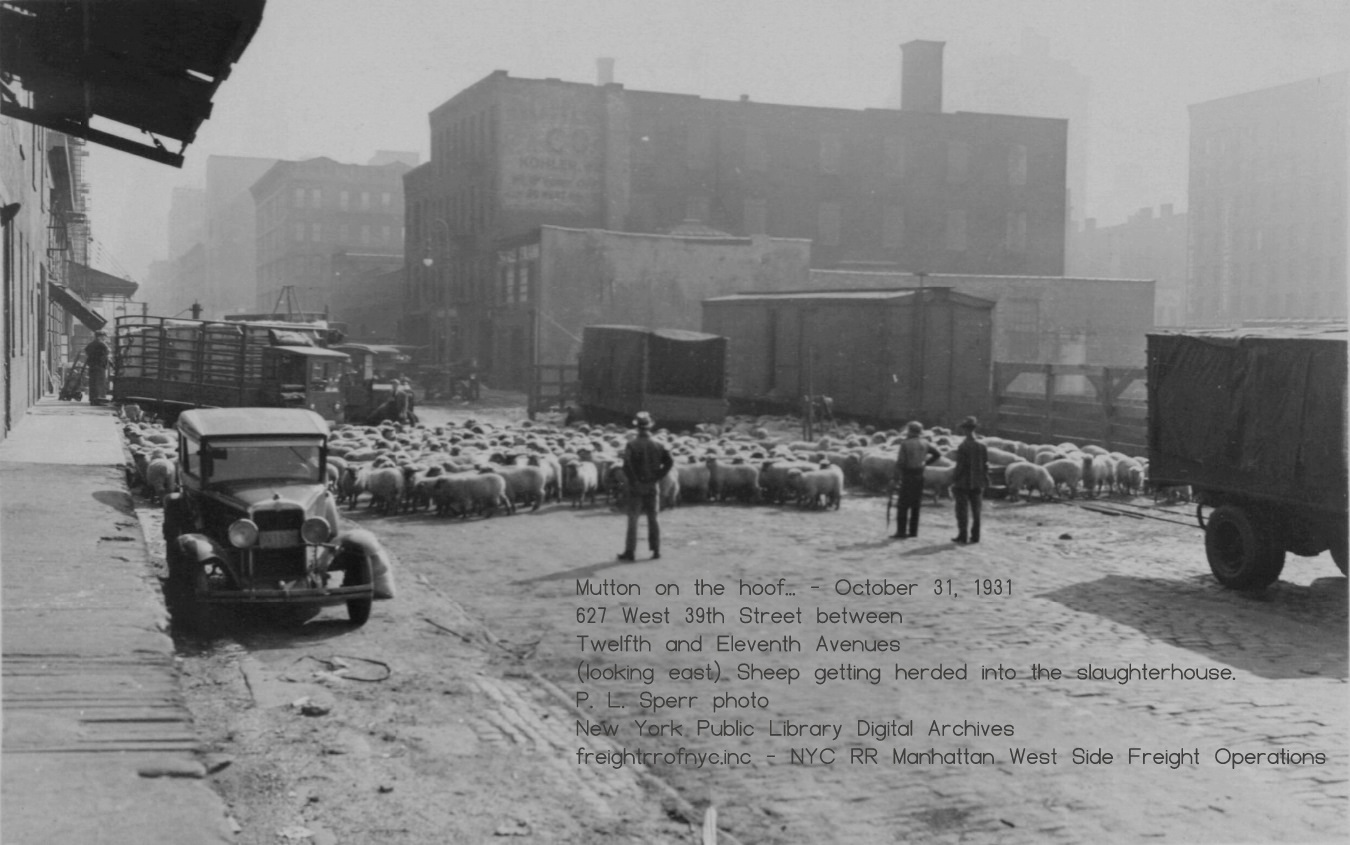

West

39th Street looking east from Twelfth Avenue. Flock of sheep being

herded into the slaughterhouse at 627 West 39th Street. - October 31,

1931

"Well Clarice, have the lambs stopped screaming?

P. L. Sperr photo

New York Public Library Digital Archives

added 28 August 2025

.

.

Empty stock cars on Eleventh Avenue at West 37th Street - February 7, 1932

Heading from Abbatoir Row towards the West 30-36th Street Yards (looking south).

New York Public Library Digital Archives

P. L. Sperr photo

added 16 August 2025

.

.

Loaded stock cars on Eleventh Avenue at West 37th Street - March 20, 1935

Heading to Abbatoir Row from the West 30-36th Street Yards (looking south).

New York Public Library

P. L. Sperr photo

added 16 August 2025

.

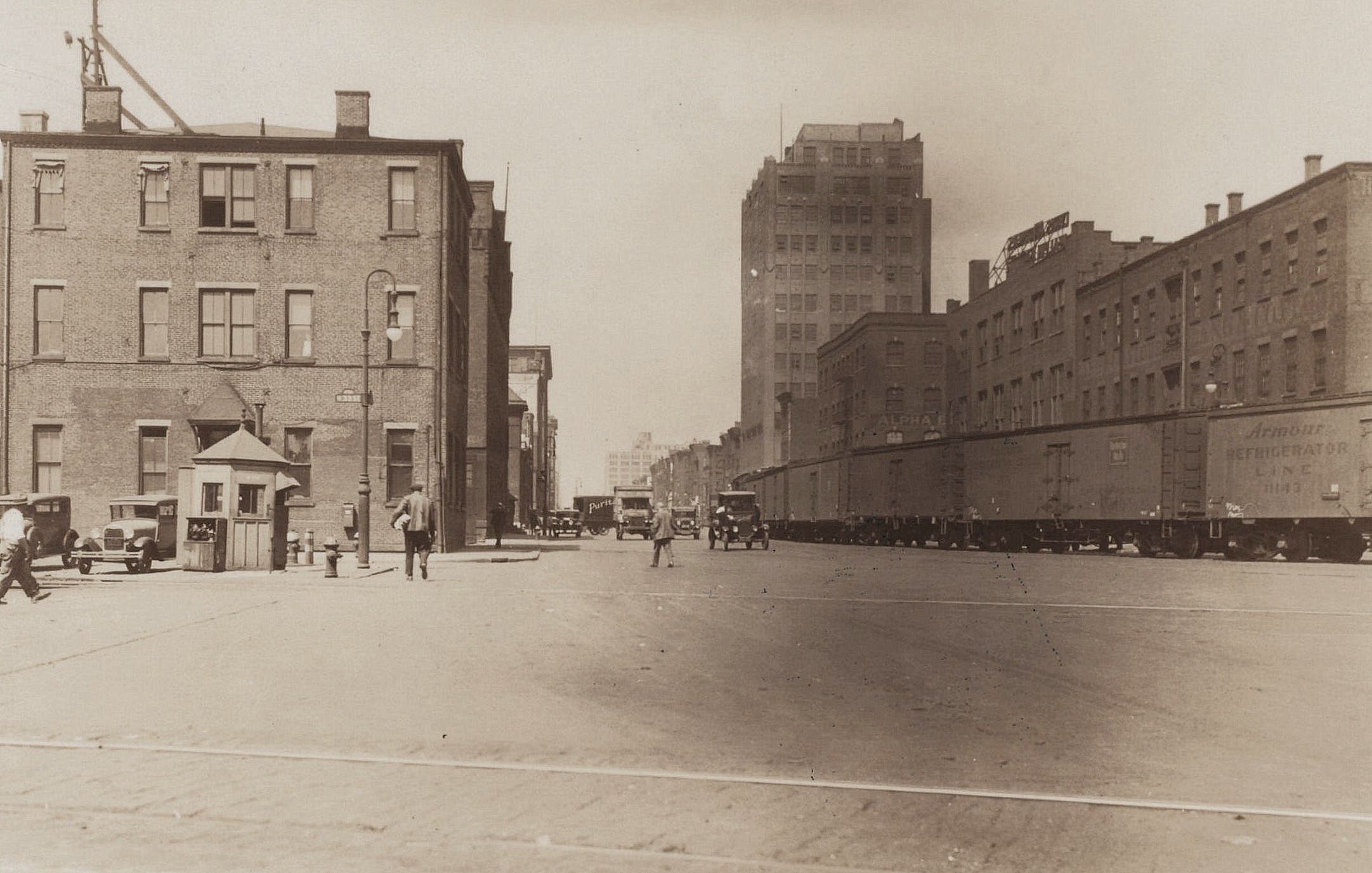

Located between West 39th, West 40th and West 41st Streets and Eleventh and Twelfth Avenues were the stock pens of the New York Stockyards Company, as well as the adjoining abbatoirs (slaugherhouses). West 39th Street between Eleventh and Twelfth Avenues was known as "Abbatoir Row".

From the 1800's through 1920's; various types of livestock (cattle, sheep, hogs) arrived by train into the various New Jersey terminals. here, they were transferred to stock boats (ferries for livestock), then ferried across the Hudson River, then unloaded and marched across Twelfth Avenue and up the side streets to the pens.

At least one newspaper anecdotal from 1986 relates the cattle broke out of the pens and stampeded at waterfront terminals. Even in normalcy; more and more street traffic became ensnarled due to the animals being herded through the street, therefore tunnels were constructed under the streets leading from the pier heads to the pens.

Over the ensuing few decades, livestock increasingly came in via the West Side Freight Line via points north and switched via stub tracks to the pens. After slaughtering; the sides of beef, hogs and such; were transported to the Meatpacking District at Gansevoort Street for butchering, packing and shipping, as well as direct wholesale and retail sales.

|

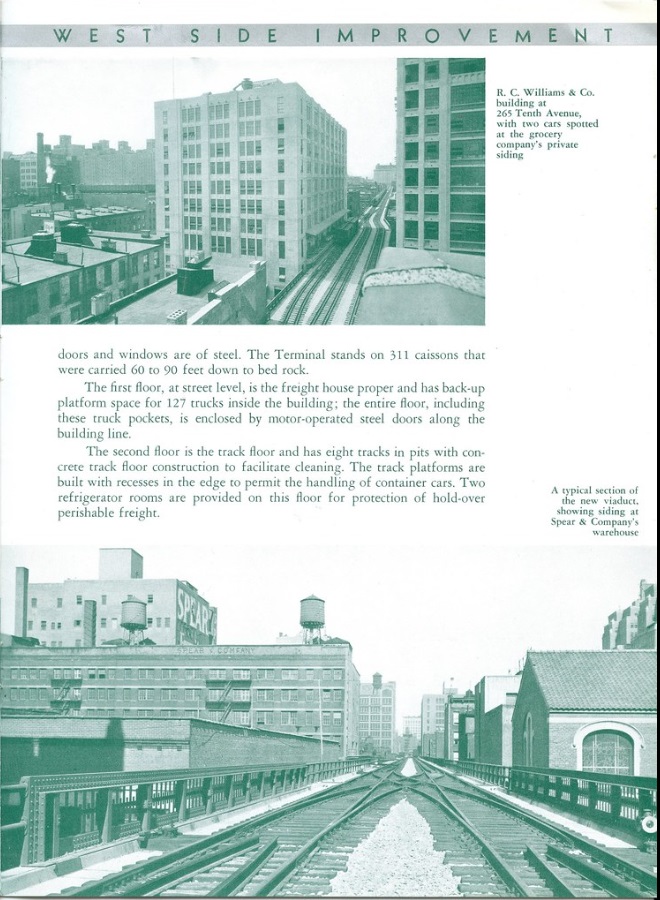

Transporting livestock by rail was effected by the use of "stock cars", and use of these cars was laborious. Cattle cars were single floor level, but hogs and sheep could be loaded into two or even three level cars for increased capacity. Obviously, they needed men to load and unload the livestock. But there was also the Twenty-Eight Hour Law. This law dictated that if livestock are being transported for longer than 28 consecutive hours, they must be offloaded for at least 5 consecutive hours to get feed, water, and rest. This law was originally passed on March 3, 1873. The law was then repealed and reenacted in 1906; and again in 1994 to set humane standards for the transportation of livestock, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture has jurisdiction and enforces this regulation. If weather or any other type of incident caused blockage of the route and as a result delayed the train carrying livestock; special arrangements had to be made. Therefore, this added considerably to transportation costs, as well as time involved. |

|

| . | |

|

For already butchered and dressed beef, veal and pork that was

coming

into the New york Metropolitan area from Midwest processors, these were shipped in refrigerator cars or

"reefers." These cars were constructed of wood with double walls, and these walls were filled with and insulated by, sawdust. "Refrigeration" was provided by blocks of ice loaded through hatches on the roof at the end of the cars and covered in salt. As the ice melted, it dripped out the bottom. These were, essentially; big oversized iceboxes on wheels. Despite the insulation, for those "reefers" traveling long distances required stopping and inspection at icing platforms at selected locations to be re-iced if necessary. Almost every major railroad yard had icing facilities. Before mechanical ice making plants, natural ice was cut from frozen ponds and lakes during the winter months, and stored in icehouses. The rest of the year, ice was drawn, from the ice house, brought to the icing platform for use. Most of the railroads in the Northeast had them. A rather quick but concise webpage has the details. Naturally, hot summer time transport required more stops for icing, while transport in the cooler months required less. Once mechanical ice making equipment was perfected, natural ice harvesting was no longer necessary. "Company" cars were owned by the meat company, such as Swift, Morrell, Cudahy, et al; and carried their advertising on the sides, which could be very ornate. As such, they were also known as "Billboard Reefers." These were usually only used by the respective company for transport of their own goods. There were also "Leaser" reefer cars, belonging to a pool of cars owned by a leasing company or a railroad, which could be leased to any firm. It should be noted that these cars could also be heated with portable charcoal or alcohol fueled heaters, to keep fresh fruit and potatoes warm during the winter months. |

|

|

|

|

| . | |

|

Finally, in the evolution of perishable transport, we arrive at

the mechanical refrigerator car. This car was developed by the 1950's. With the advent of the compact mechanical refrigeration units, railcars were were now constructed with built in refrigeration units, and could travel hundreds to thousands of miles with minimal intervention. These are known as the "mechanical reefer."

But also occurring around this time, the urban development of

Manhattan with industrial properties being converted to commercial and

residential; slaughterhouses were increasingly vacating the

New

York City area. As a result, the slaughterhouses relocated to

closer to the stockyards in Chicago, Kansas City and Abilene; and now

were able to ship dressed meat to the east under reliable refrigeration

with no This is the only surviving method of perishable transport in the present day. |

|

So in short, the process was this:

.

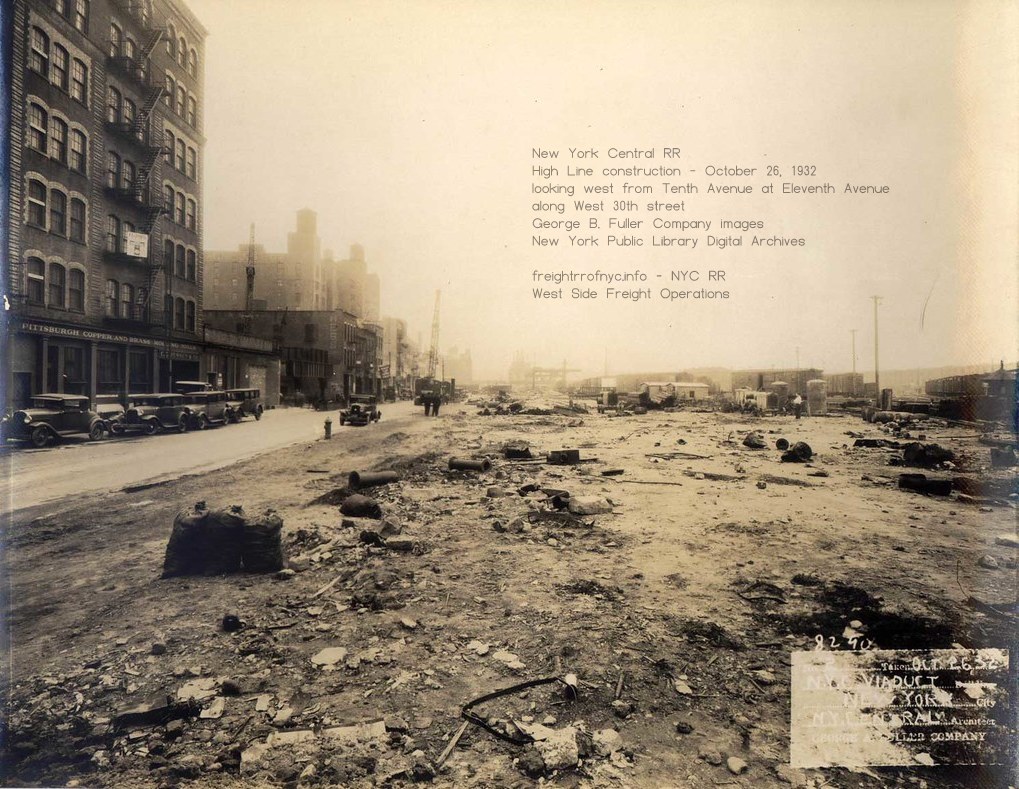

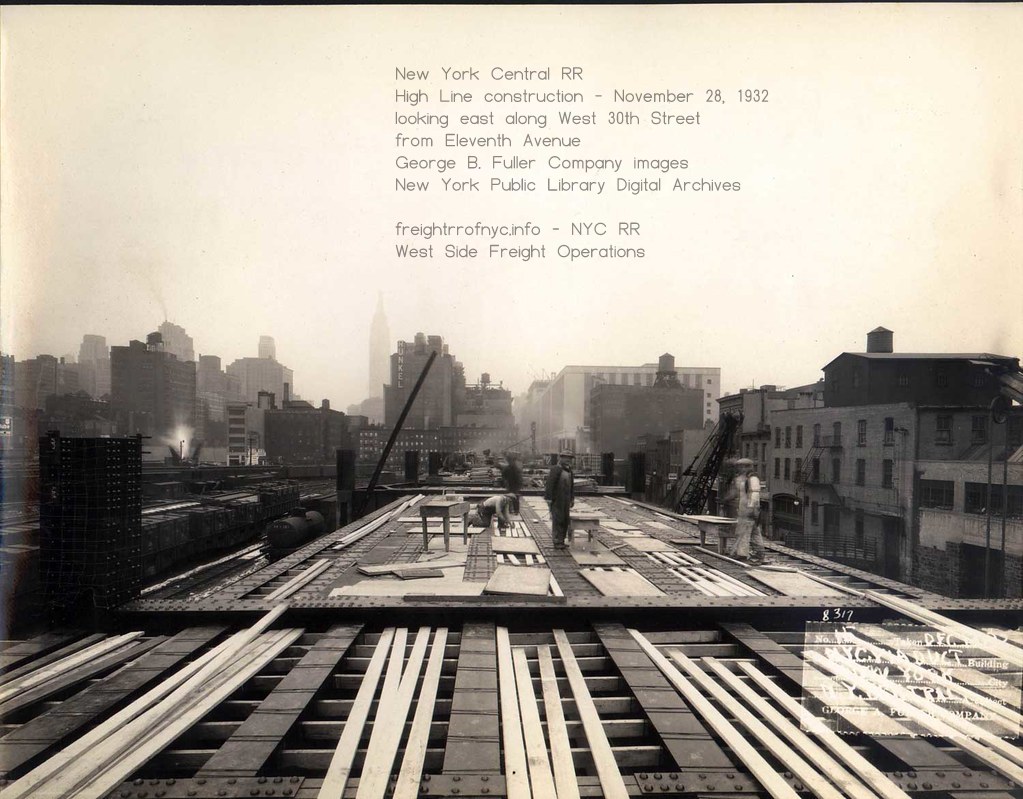

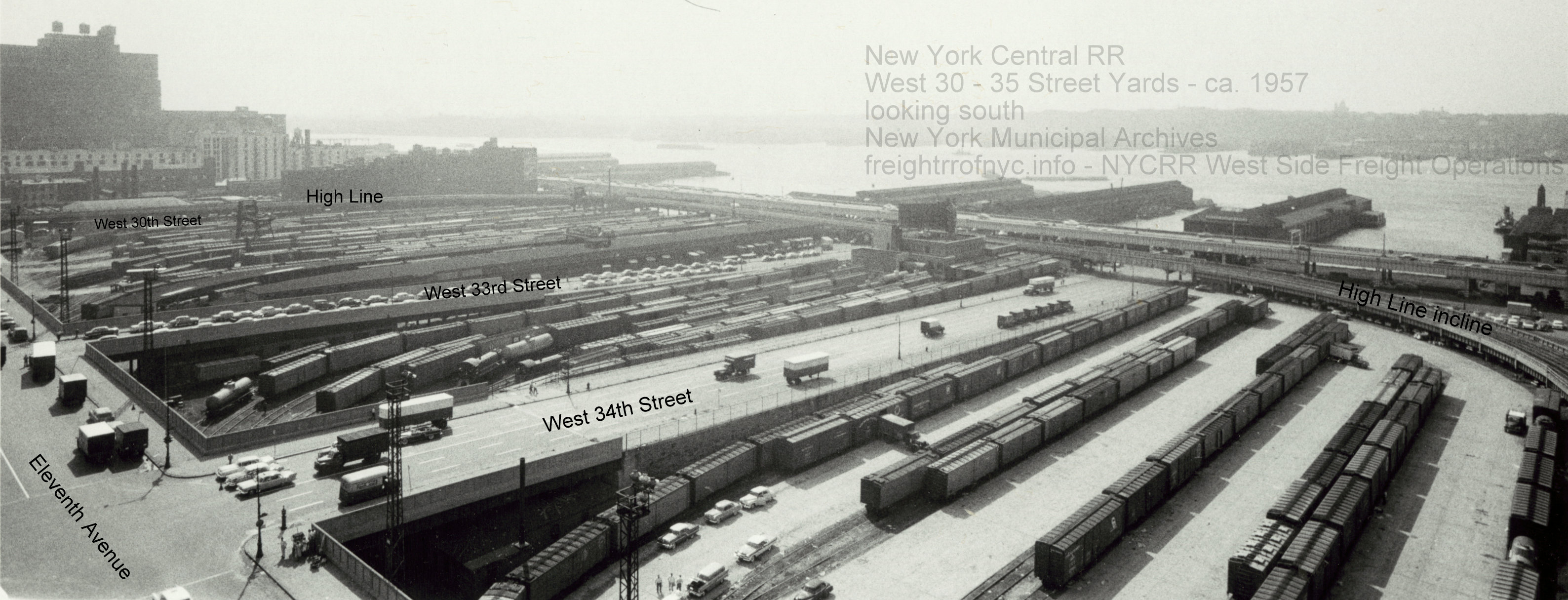

West 36th Street to West 30th Street & Twelfth through Tenth Avenues - Freighthouses and Yard Complexes

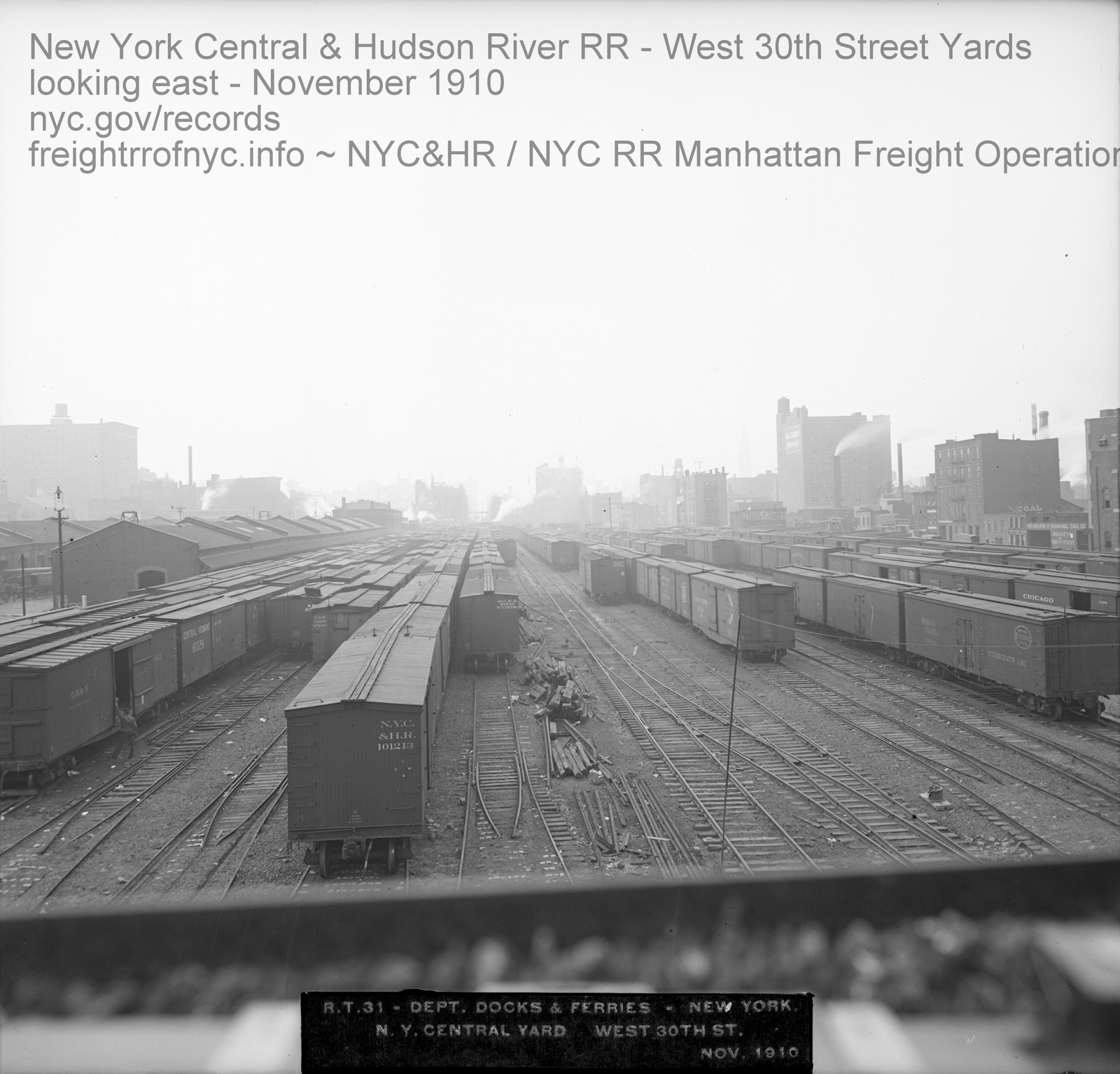

The West 36th and West 34th Street Freight Yards and the West 33rd Freight Station were in fact two separate yards but connected extensively by trackage, and were divided by West 34th Street.

Therefore, despite being listed as two separate yards, it was in actuality one large yard. The reason for this, was the West 36th Street Yard was originally owned by the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railroad or "West Shore"; which was a competitor to the New York Central early on.

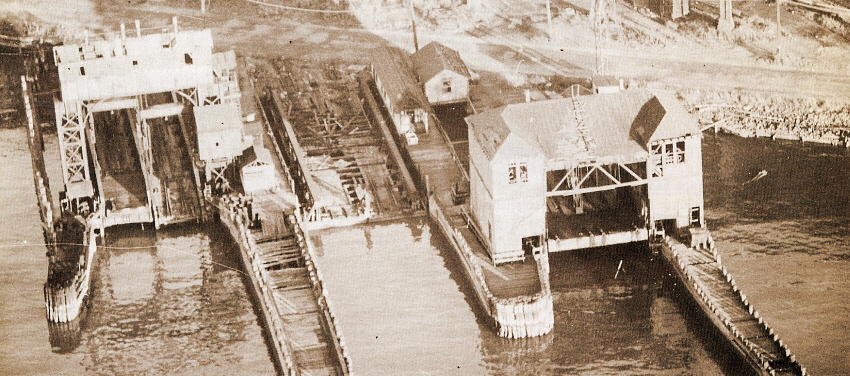

West 33rd Street - Transfer Bridges

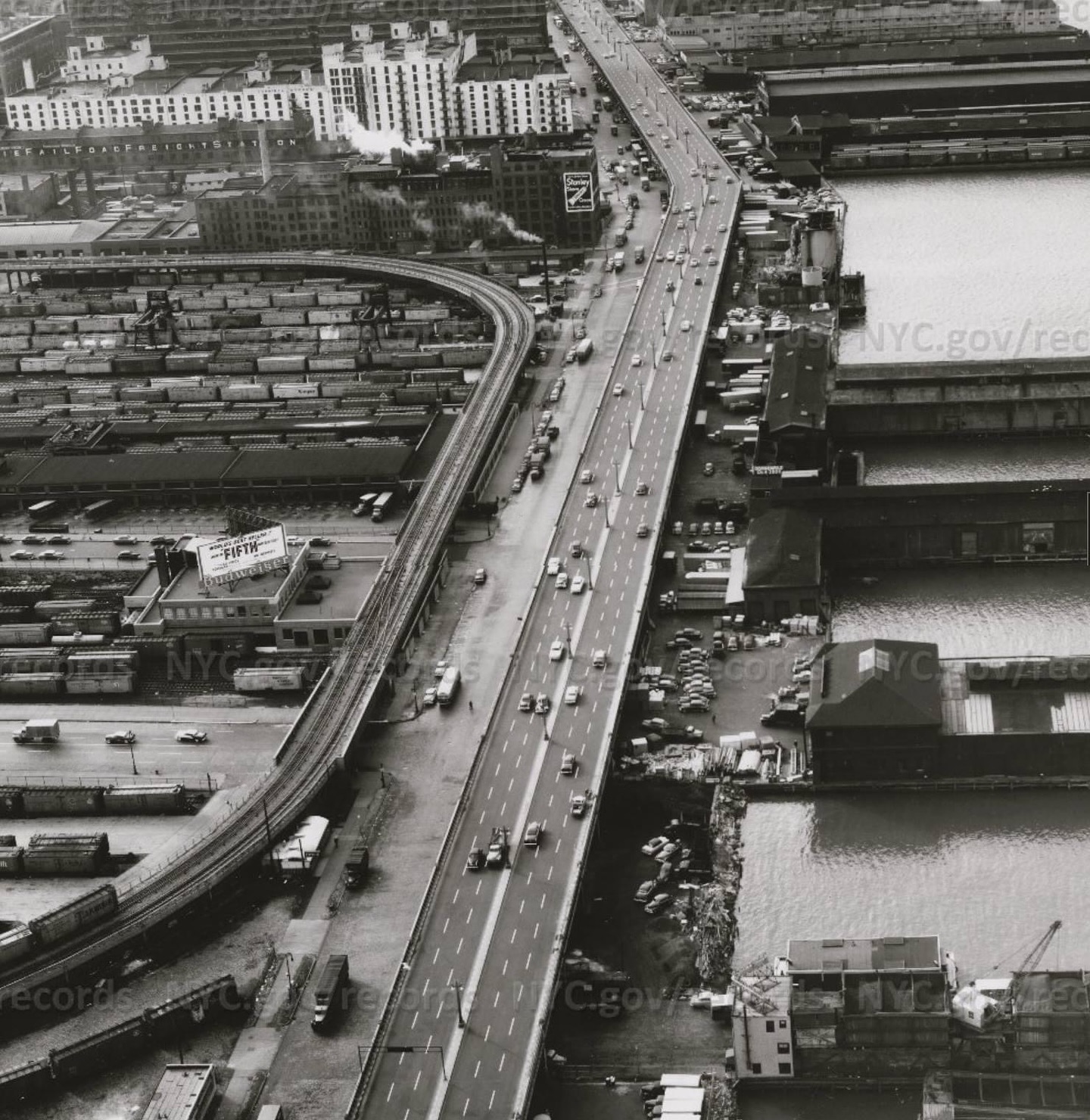

The New York Central also had another pair of transfer bridges located between Piers 73 and 72; of which trackage was connected directly to the freight yards and terminal at West 33rd Street. These would be the first transfer bridges located in Manhattan to shut down by New York Central circa 1943 and possibly even earlier; while the transfer bridges north at West 60th Street Yard would remain in service until 1968.

Looking east from Hudson River at

West Side, Manhattan, NY - 1929

Piers 73 and 72, with West 33rd Street Transfer Bridges.

added 05

April 2024

.

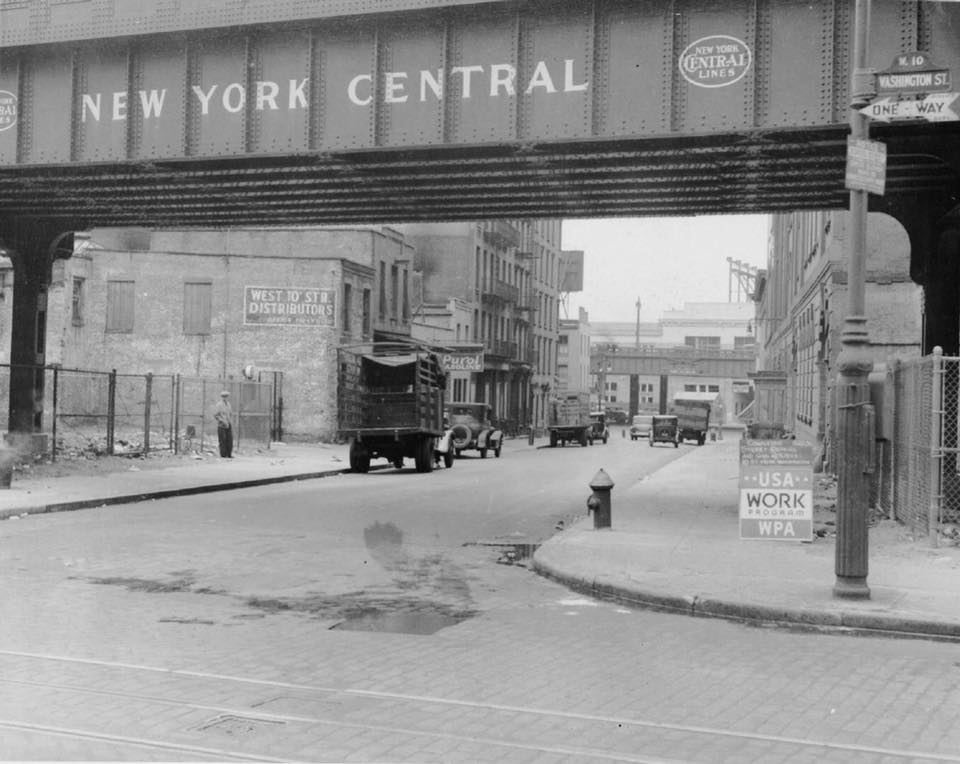

But, as we have read; and despite having the rail-marine connections via the transfer bridges here at West 33rd Street; New York Central freight trains would literally travel down the centerline of several main thoroughfares, bringing freight to and fro the various terminals in Manhattan, as well as several customer sidings along the route.

A regulation stipulated that south of West 34th Street, conventional locomotives could not be used; so the cars were drawn by a dummy engine. A dummy engine was nothing more than a conventional steam locomotive with an outer car body that resembled a passenger car. North of 34th Street, a conventional locomotive could be used. Why 34th Street? 34th Street was the crosstown line of demarcation where it was thought that no to minimal development would take place. North of 34th Street then, was considered suburbia giving way to rural, with farmlands extending to the Harlem River. Oh, how they would soon learn that there were no limitations to be placed on urban sprawl!

.

West 33th Street - unidentified

Tri-Power [DES-3] entering yard from Eleventh Avenue.

Looking northwest at West 32th Street,

Manhattan, NY - March 17, 1929

P. L. Sperr

photo

NYPL

Digital Archives

added 05

April 2024

.

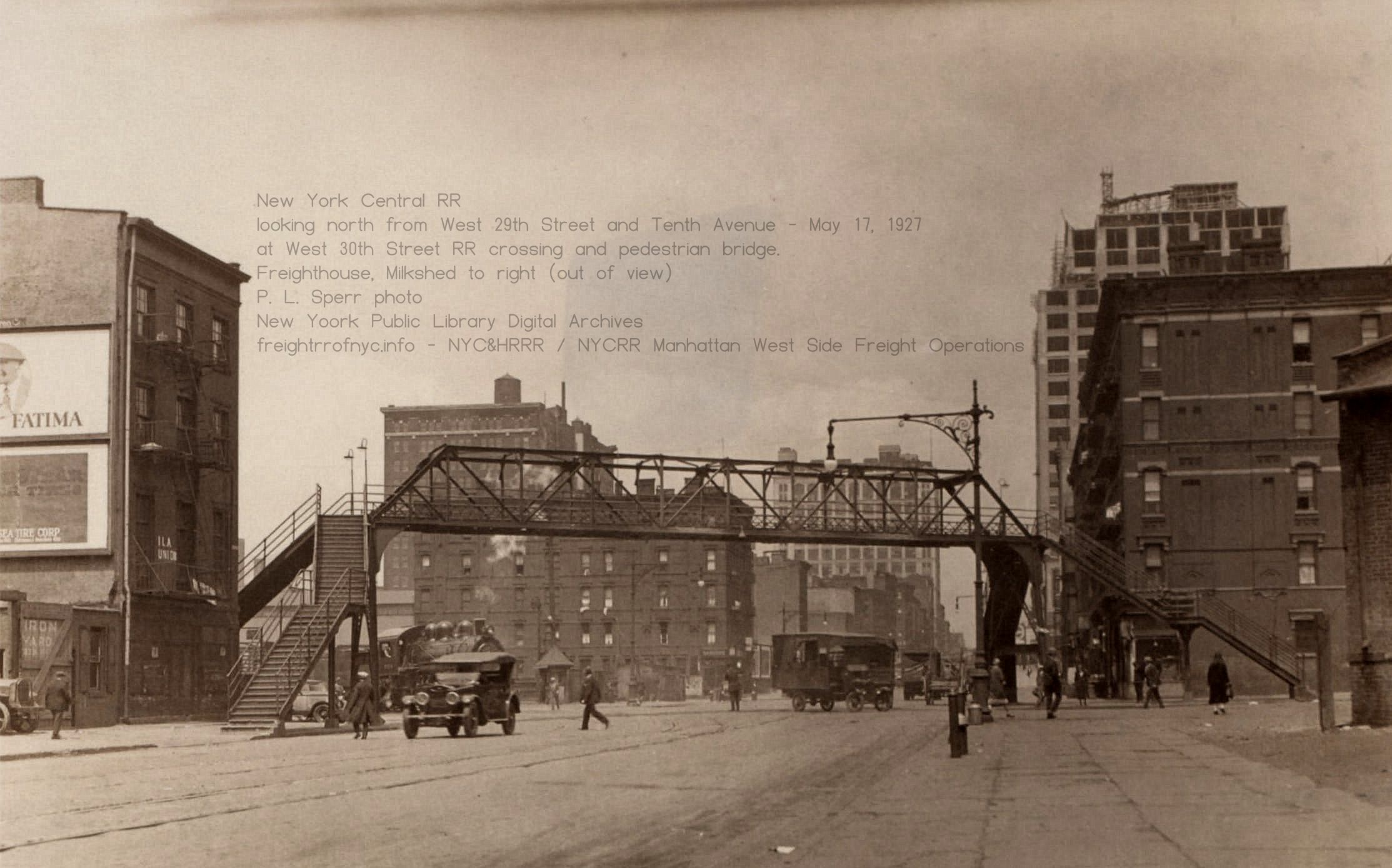

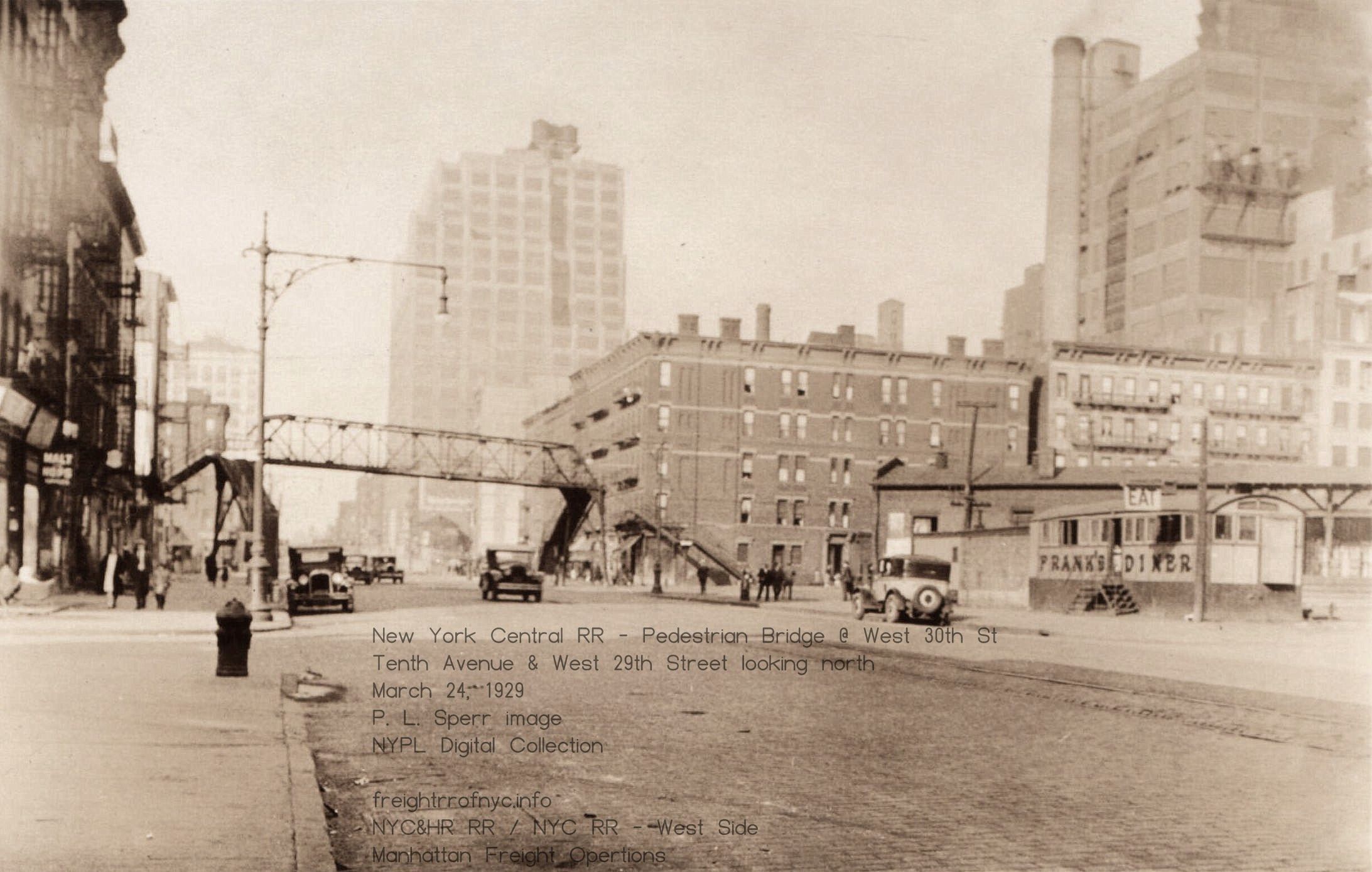

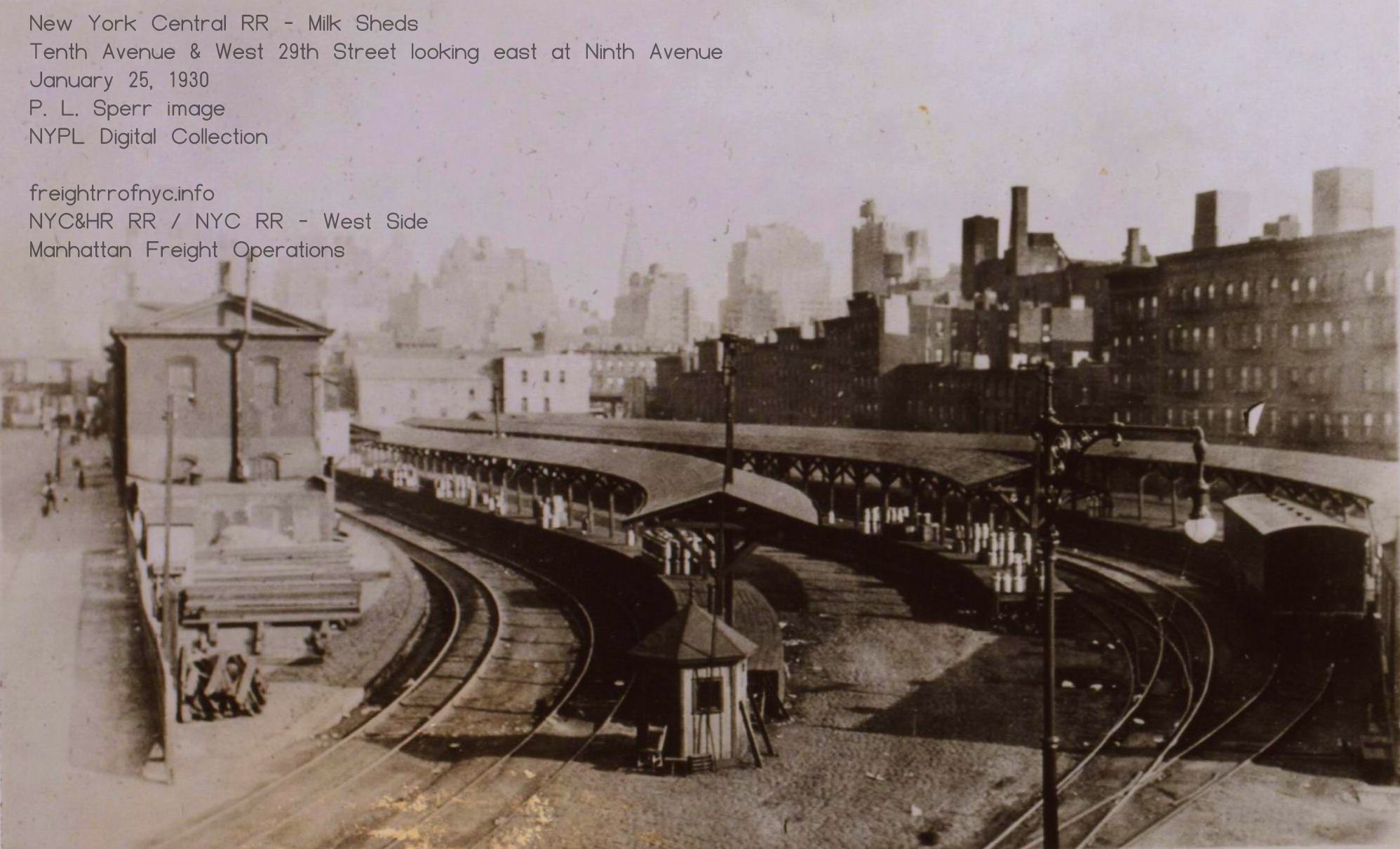

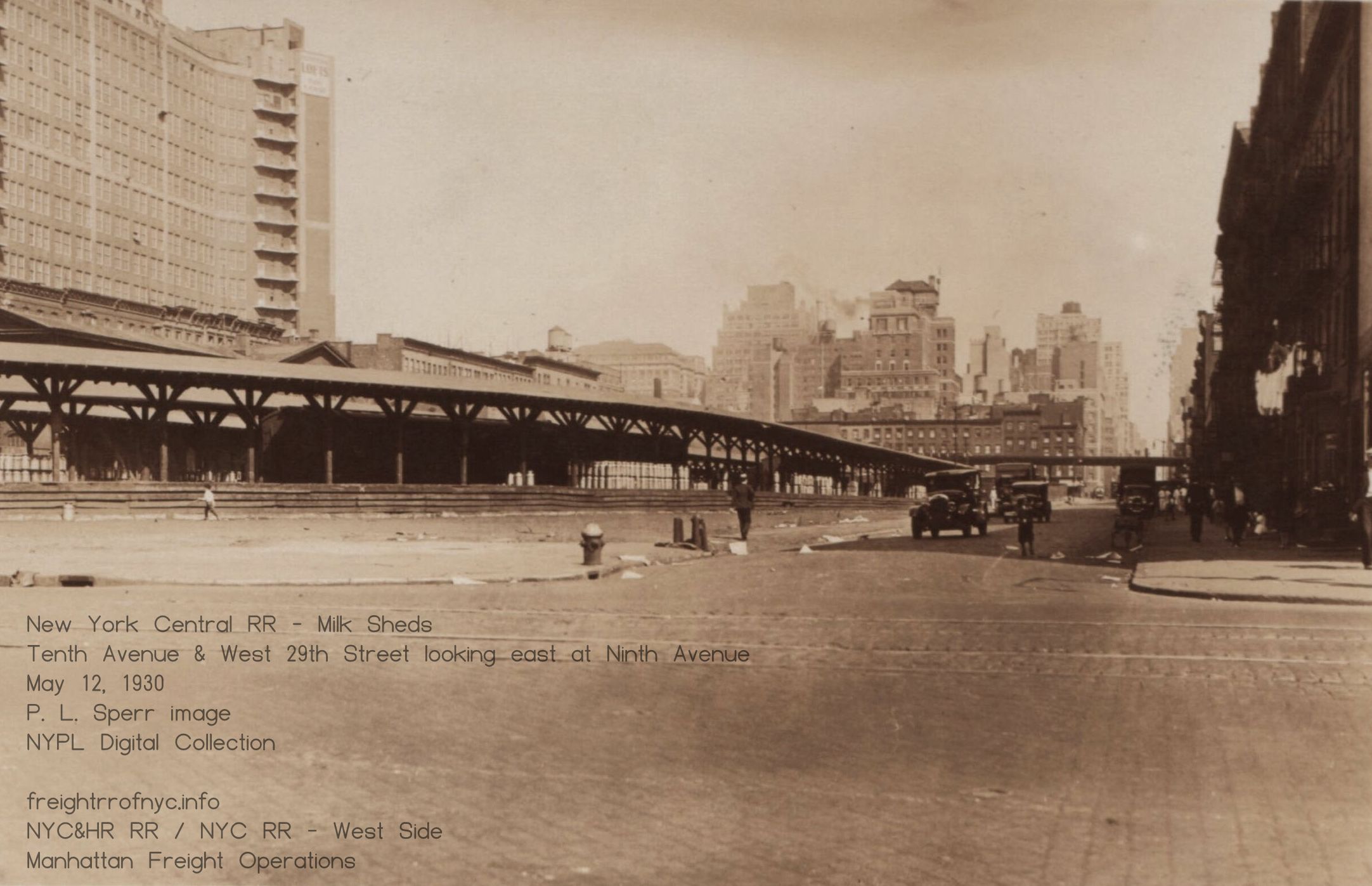

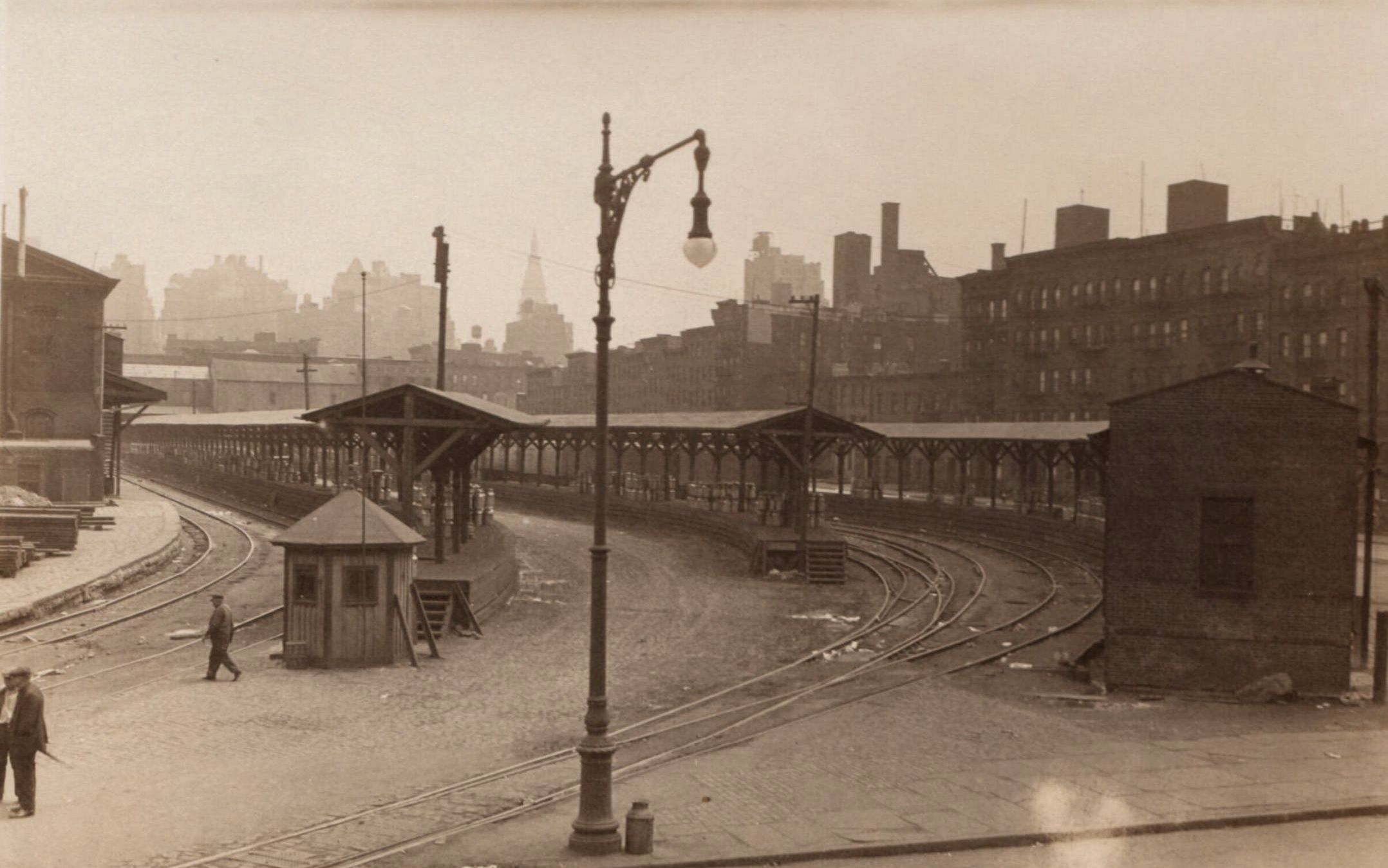

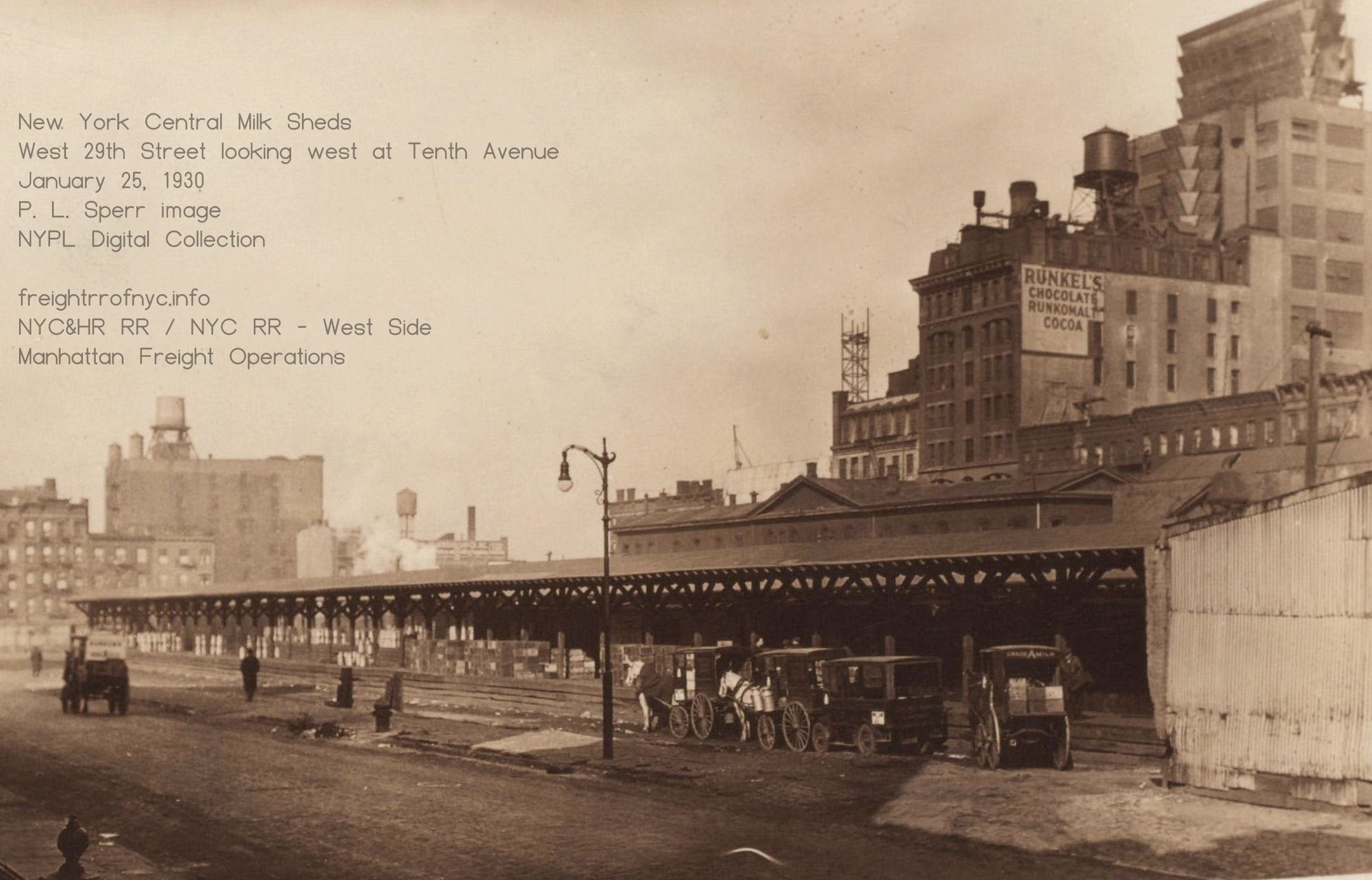

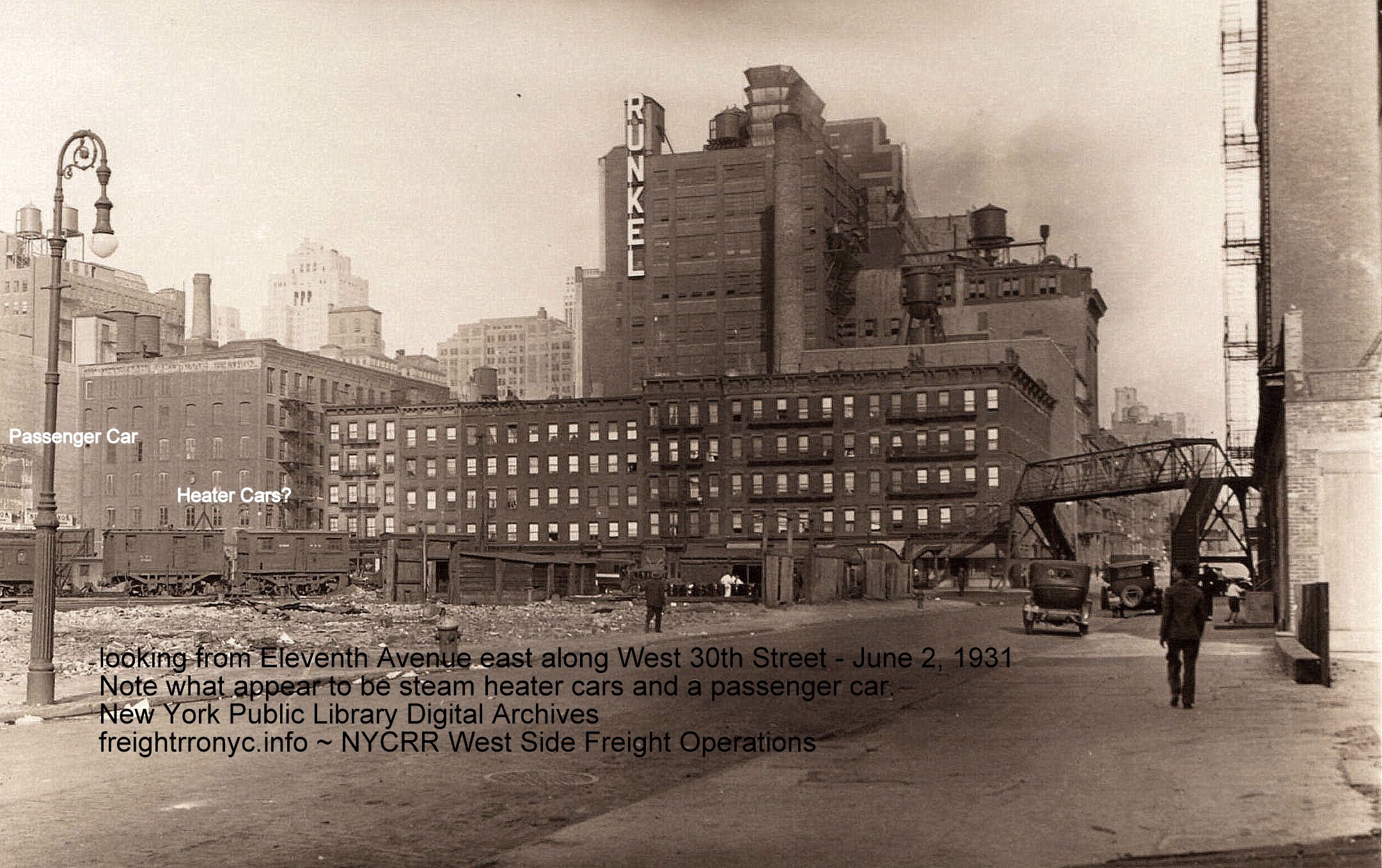

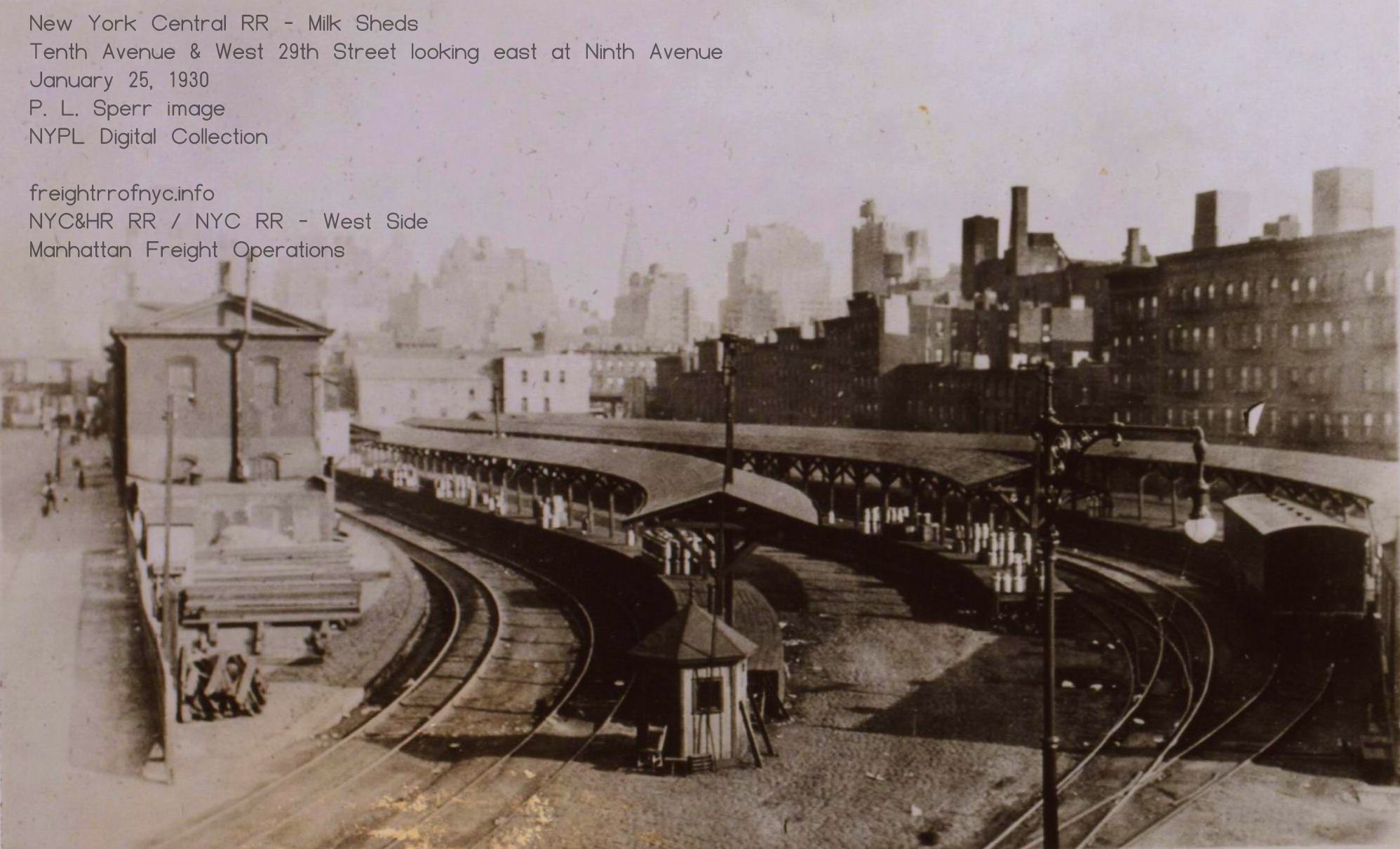

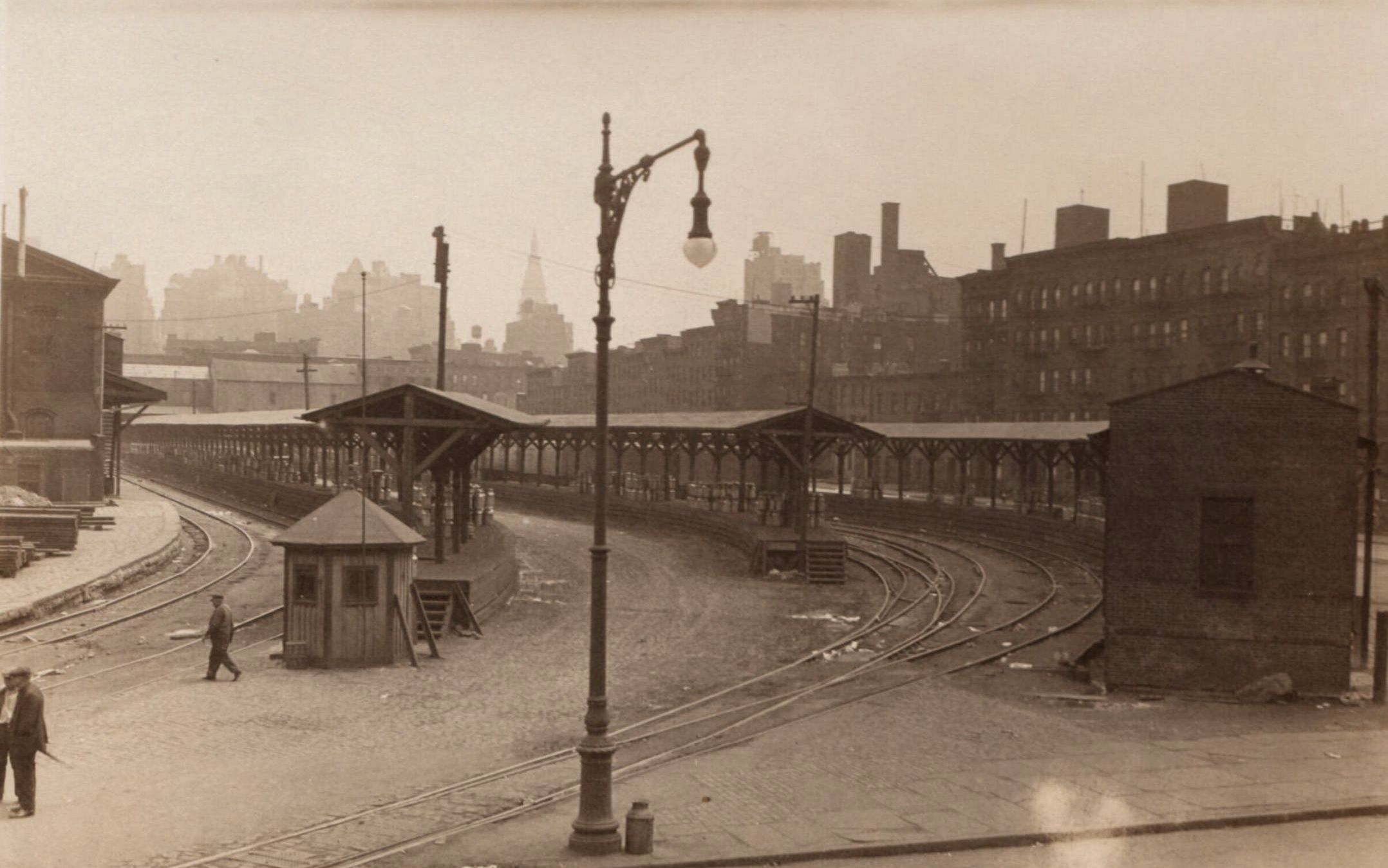

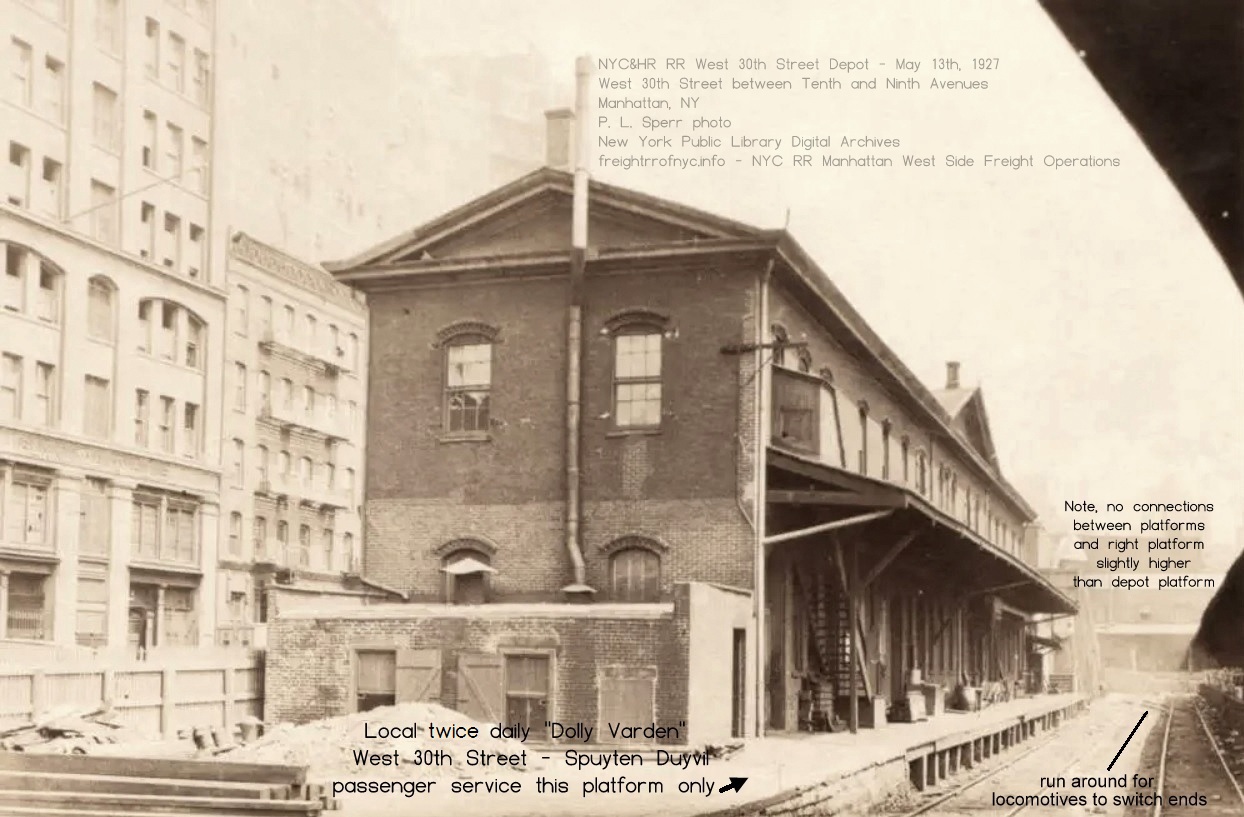

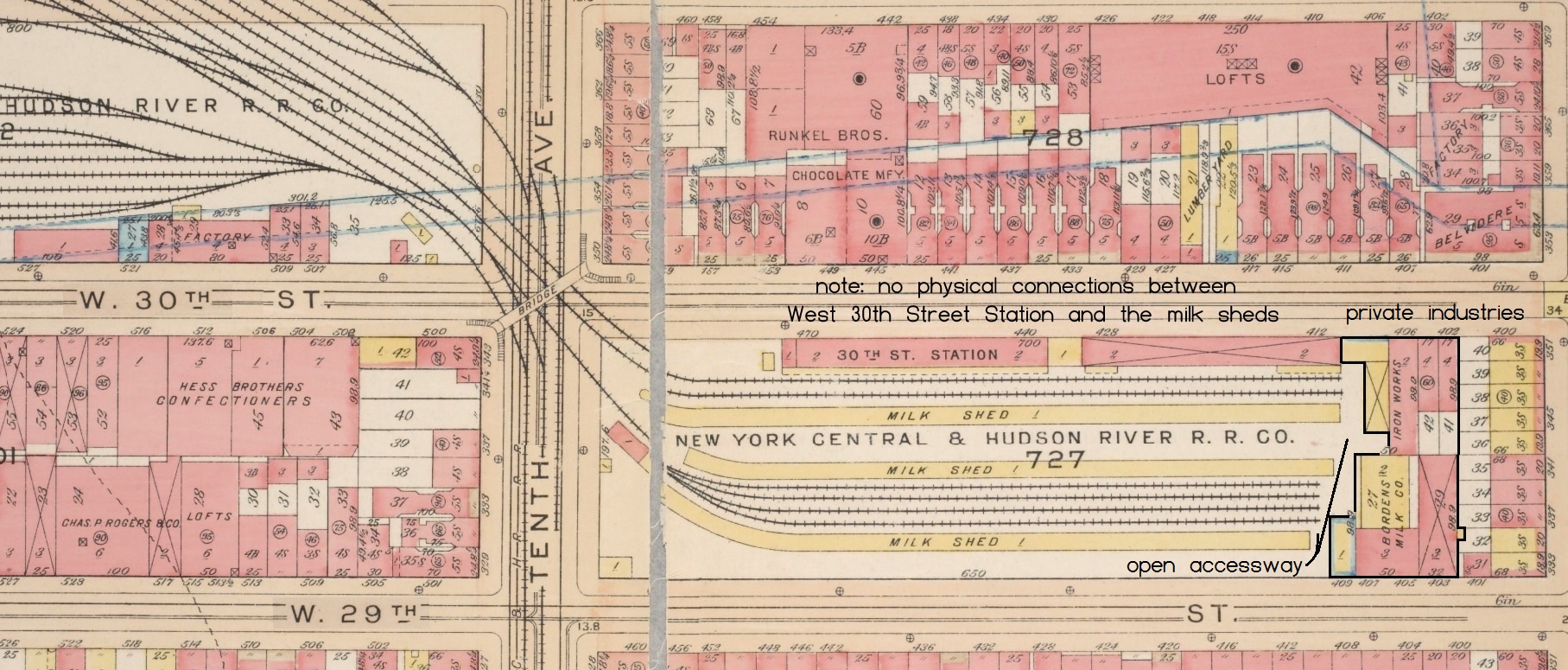

Tenth Avenue and West 29th and West 30th Street - Milk Sheds

Located between West 30th Street and West 29th Street Ninth and Tenth Avenues, were the Milk Sheds.

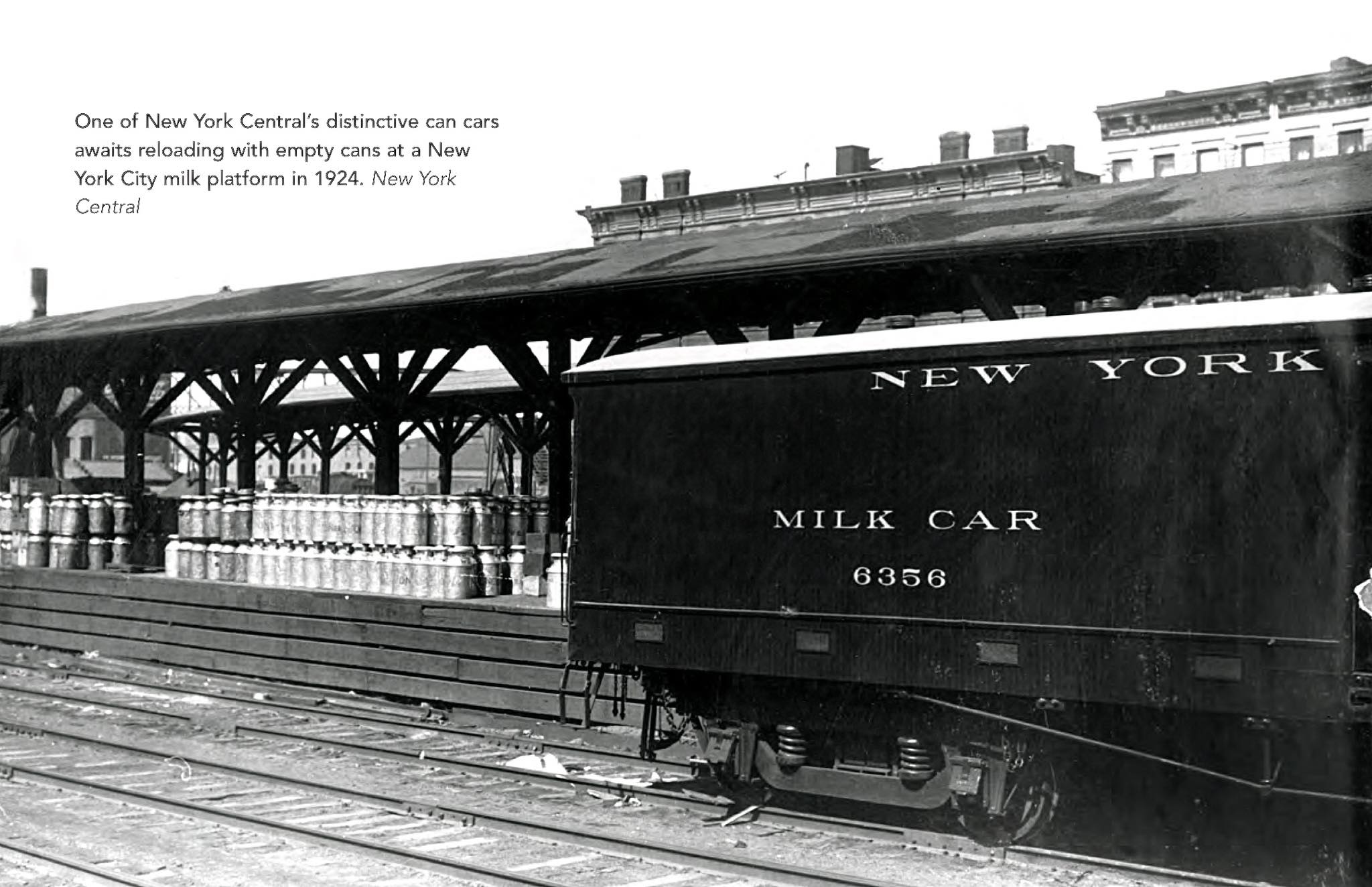

These were long roofed platforms and the west ends were curved to accommodate the trackage entering diagonally from the yards between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues. These platforms were dedicated for the use of unloading full milk cans and crates of dairy products (cheese, cream, etc.) from reefer cars, and usually specially marked "MILK". These cars were also known as "can cars."

The milk was then transported to bottlers where it was sold to the public or sent to schools and institutions. Empty milk cans were returned to the platform in the evenings, loaded into the milk cars and brought back to the dairy farms in Upstate New York for reuse.

|

Out of all the railroads entering the New York area, the New York Central RR carried the greatest share of milk. Obviously, the benefit of bringing it directly into Manhattan was a significant factor for this. There were three milk stations that were served by the West Side Line:

Borden's had a plant at 615 West 131st Street (beginning 1937), and Sheffield had three: 632 West 125th Street, 524 West 57th Street, 529 West 28th Street. |

|

Referencing the platforms seen in the images, I shall discuss these at length in the chapter "Those Platforms"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

milkshed images: New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photos milkcan: eBay Milk

cans were usually embossed with the name of the farm "Elgin" (of the

Catskills), or the cooperative that the farm belonged to

Dairyman's League (DairyLea) or the dairy company: Crowley, Sheffield, Queensboro, etc Painted numbers were used to track the can and either painted letters or embossed tags for the railroad which carried it and the milepost that can was dropped off and received from. U&D - 51 (Ulster & Delaware MP51 - Kelly Corners) O&W - New York Ontario & Western Rwy NYC - New York Central, etc. Ergo, this can is marked NYC, for New York Central. |

| Here we see milk men with horsedrawn wagons (and a very primitive internal combustion powered truck!) lining up. By Spring of 1931, these milksheds will be razed and the property developed into the US Parcel Post Building. |

||

|

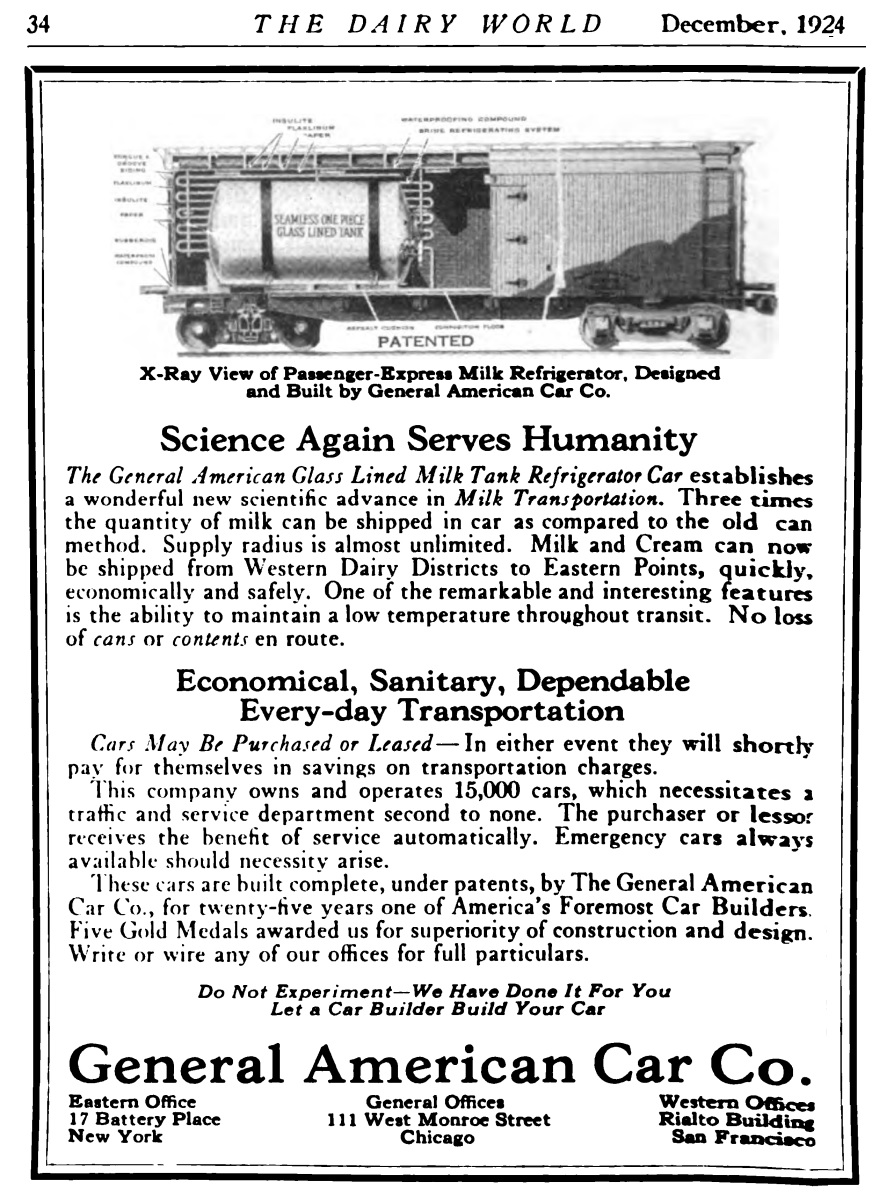

Transportation via the milk cans above was the first era of milk transport. During the mid 1920's; a less labor intensive and more economical way method of transport was developed. This was the express milk tank car. The end of one can be seen in the top left image above. From outward appearances, it looked like a non-descript elongated box car or perhaps a railway express car. But internally, it was revolutionary. The interior contained two glass lined tanks of two to three thousand gallon capacity. These cars also incorporated a brine refrigeration system (instead of manually loaded blocks of ice); and a motorized system of paddles in the tanks to keep the butterfat from separating from the milk. Not only were these two tanks easier to clean and sterilize (than the many individual cans), it also reduced the amount of labor needed for transport of milk. All that was required was one, maybe two men; and hoses from the trackside dairy tanks to the car, to fill the tanks. At the bottlers, the same. The small armies of husky men to unload the thousands of milk cans at the destinations were no longer required. Neither were the milk sheds taking up vast amounts of space. |

| Following

both the advent of the express milk tank cars and the relocation of

rail traffic to the sub-grade cut between West 60th and West 36th

Street, the milk platforms at West 29th Street were demolished and new

ones constructed at the southeast corner of the West 60th Street Yard.

Following shortly thereafter the construction of the sub-grade cut in 1937, Sheffield Farms built a new processing plant directly next to the this cut at West 57th Street, and a dedicated rail siding constructed just to service this facility. Construction of this siding can be seen in the June 30, 1937 image. This new Sheffield facility consolidated the operations of their three older and smaller pre-existing processing plants located in Manhattan:

|

|

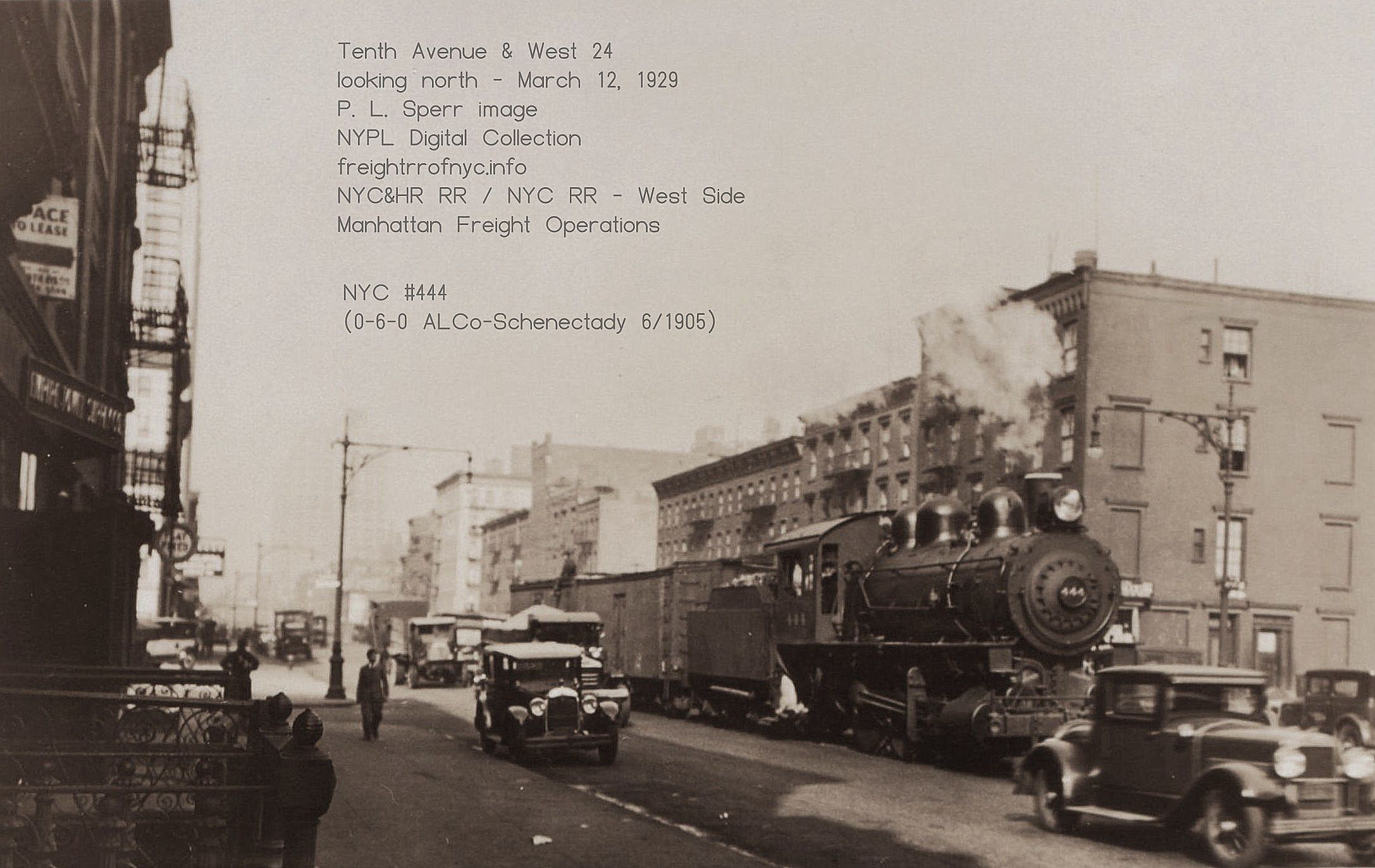

Tenth Avenue & West 24th Street

NYC #444 [0-6-0, ALCo 1905] heading south on Tenth Avenue at West 24th Street

New York Public Library Digital Archives

P. L. Sperr photo

added 19 August 2025

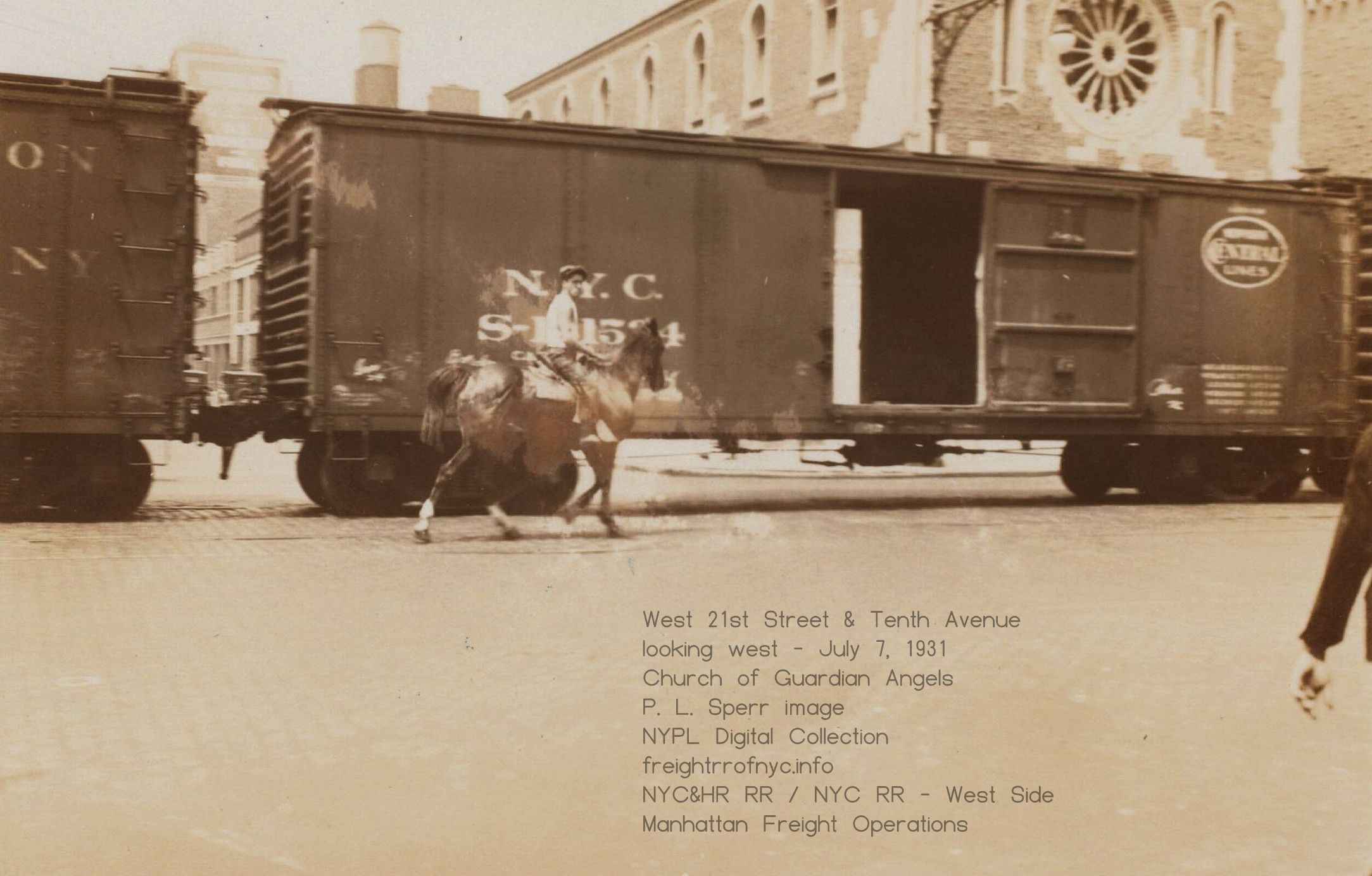

Tenth Avenue & West 21th Street

Church of Guardian Angels

|

|

|

West 21st Street and Tenth Avenue (looking west) - July 7, 1931

Church of Guardian Angels. In less than two years, the High Line will be built behind the church. New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

|

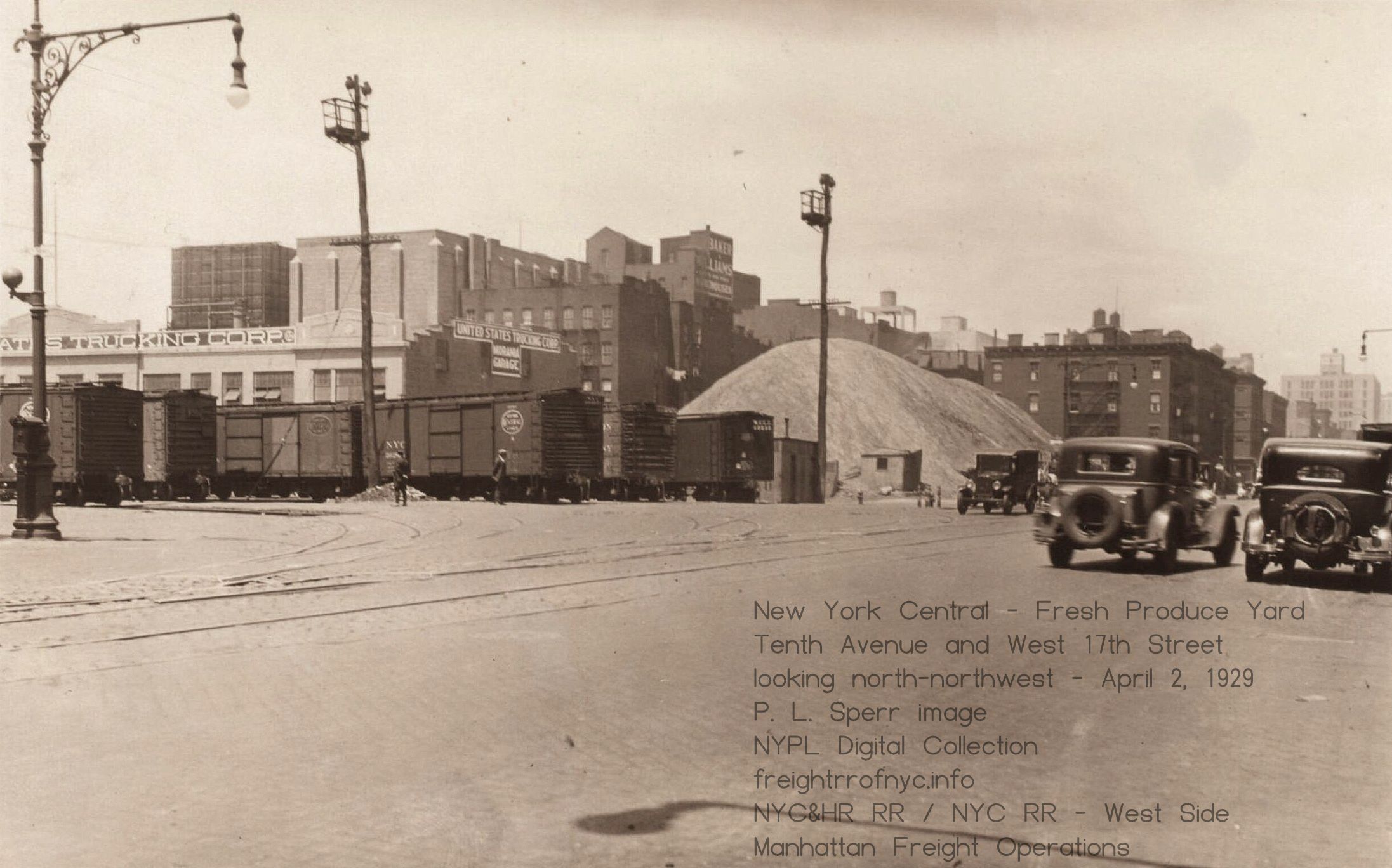

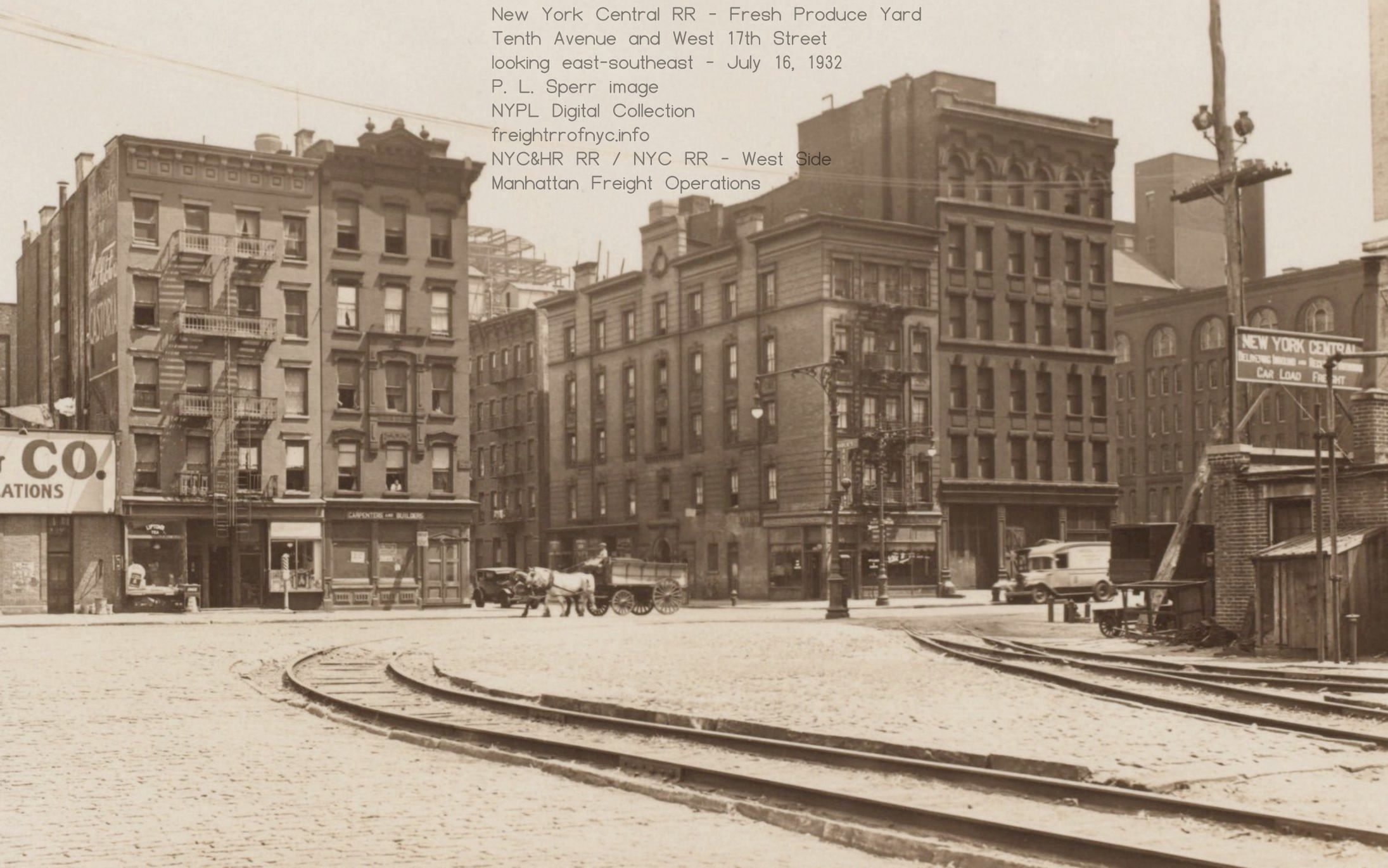

Tenth Avenue & West 17th Street - Fresh Produce Yard Team Tracks

United States Trucking Corp.; B & J Auto Spring

Tenth Avenue & West 17th Street (looking northwest) - April 2, 1929

United States Trucking Corp. New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

| . . |

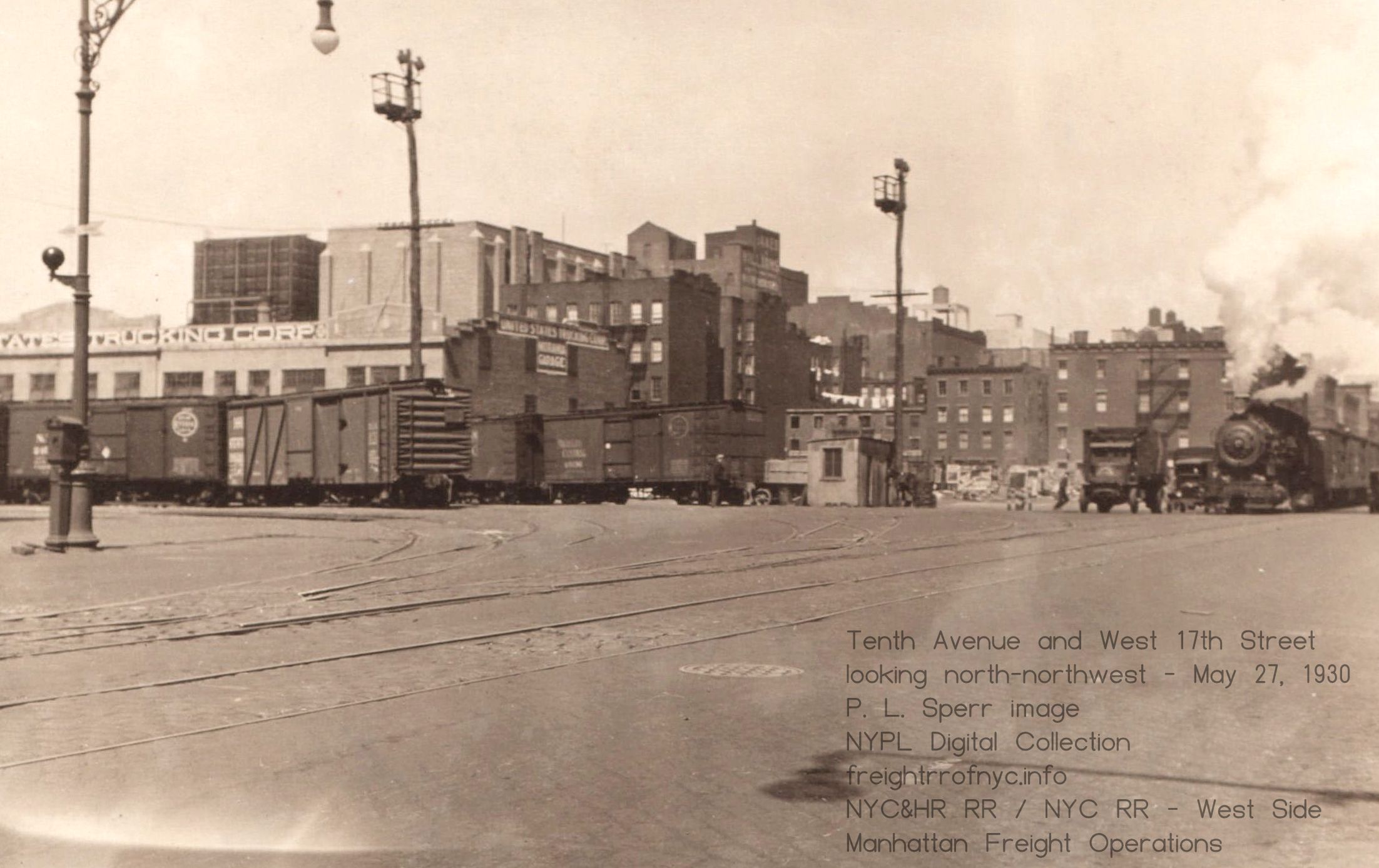

Tenth Avenue & West 17th Street (looking northwest) - May 27, 1930 New York Public Library Digital Archives United States Trucking Corp. P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

| . . |

Tenth Avenue & West 17th Street (looking east-southeast) - July 16, 1932

New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

| . . |

Tenth Avenue & West 17th Street (looking east) - July 16, 1932 Looking east from Eleventh Avenue. B&J Auto Spring on Tenth Avenue. New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

| . . |

NYC #1534 coming onto on Tenth Avenue from the West 17th Yard Looking northwest. United States Trucking Corp. New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

| . . |

NYC #1532 coming north on Tenth Avenue, #1534 waiting to pull onto Tenth Avenue from the West 17th Yard (looking south) New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

| . . |

From Eleventh Avenue and West 16th Street - April 2, 1929 United States Trucking Corp. (looking northeast) New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

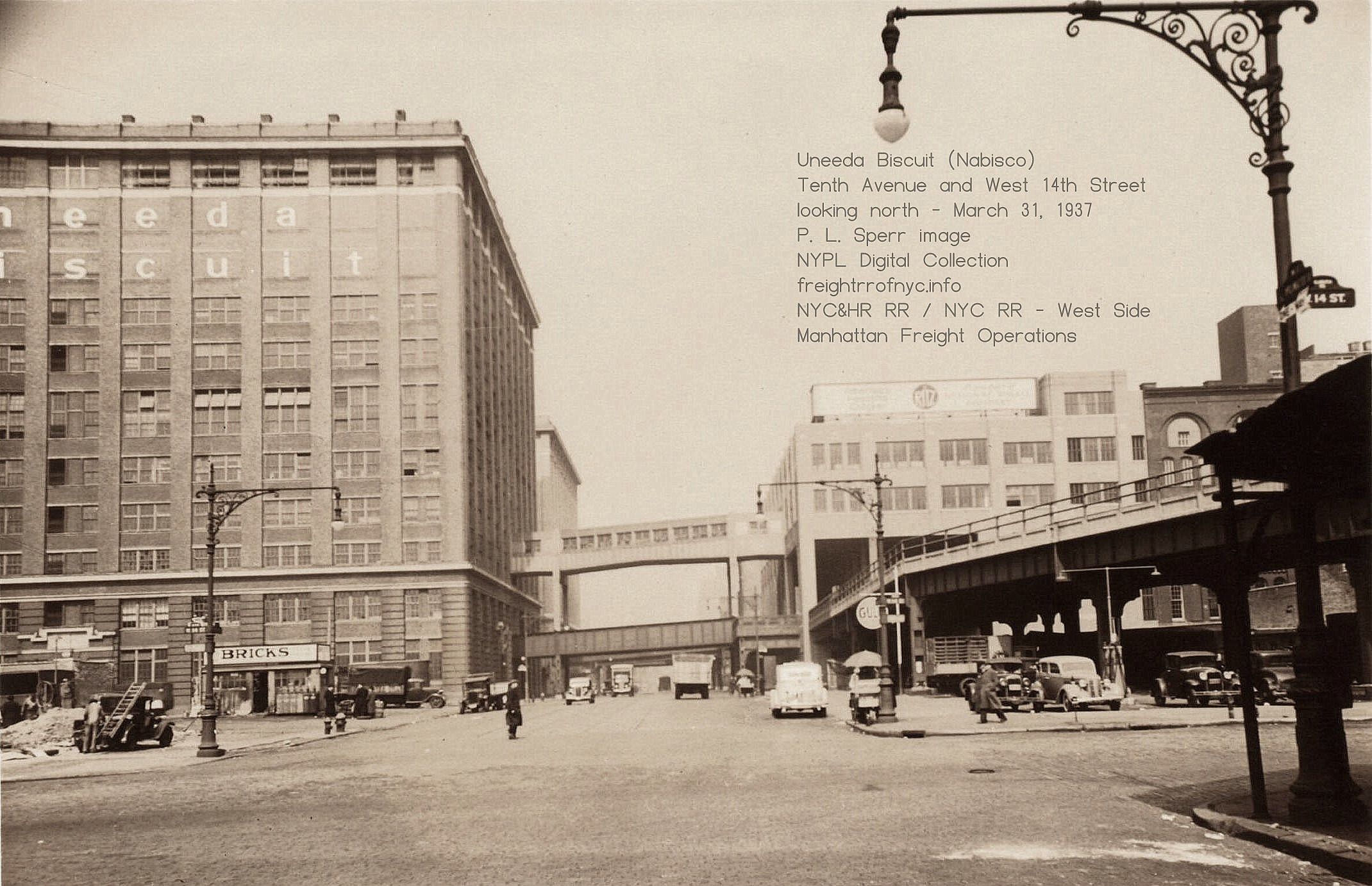

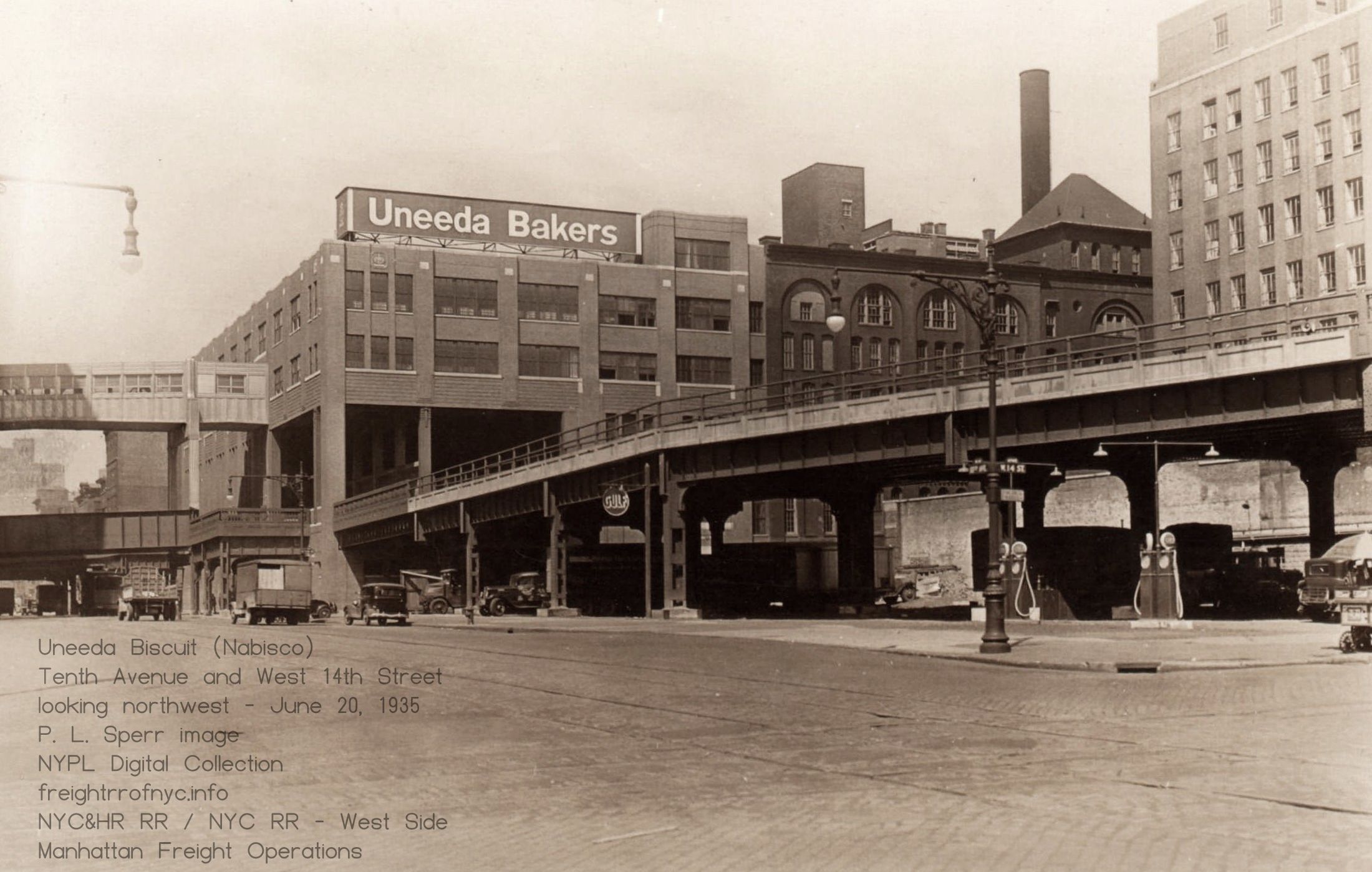

Tenth Avenue & West 14th Street - Uneeda Biscuit / Uneeda Bakers (Nabisco)

Tenth Avenue & West 14th Street (looking north) - July 24, 1924 pre-High Line New York Public Library Digital Archives Standard Photographic Service Borough President of Manhattan added 19 August 2025 |

| . . |

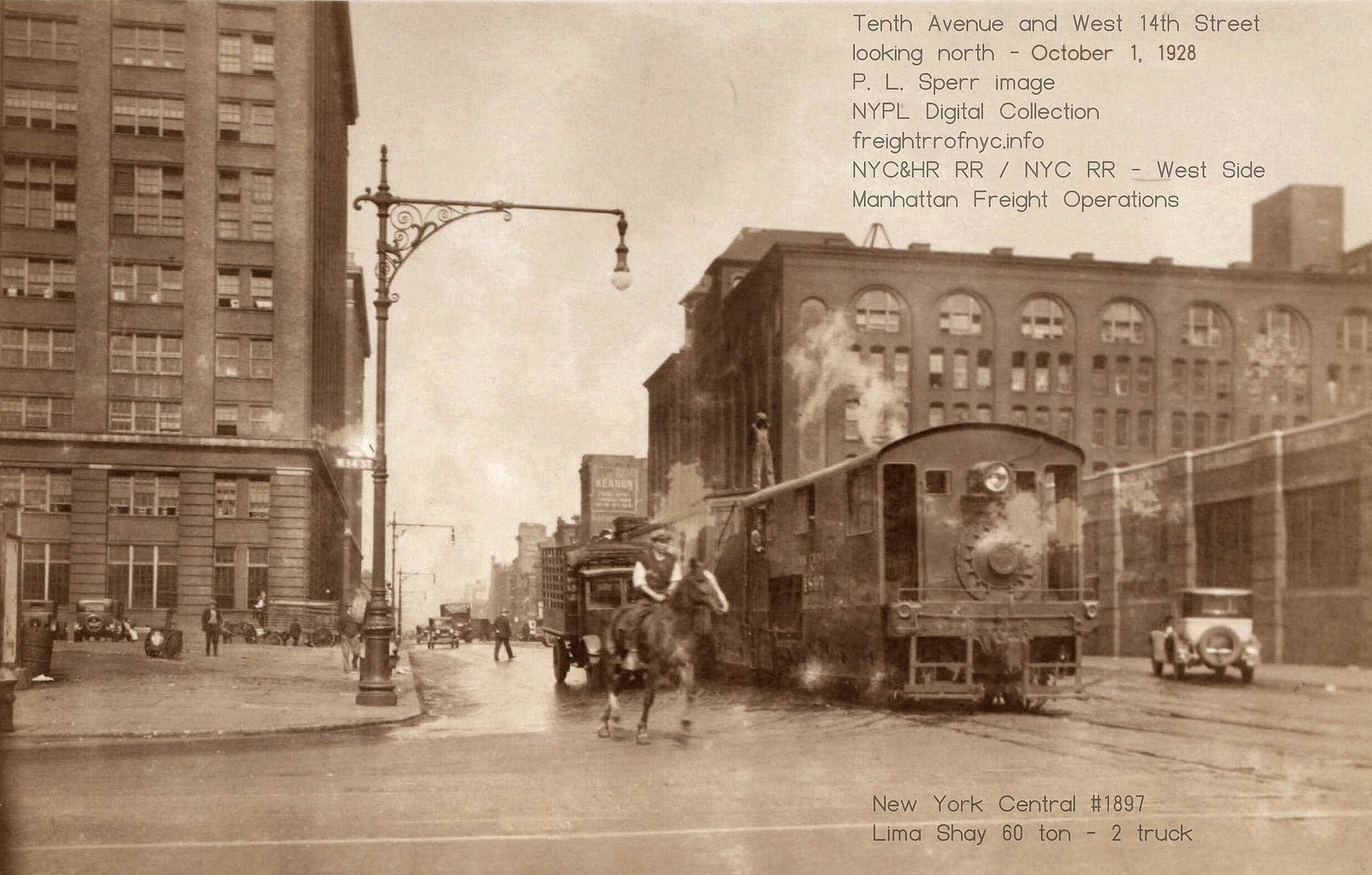

Tenth Avenue & West 14th Street (looking north) - October 1, 1928

pre-High Line NYC #1897 (Lima Shay) New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

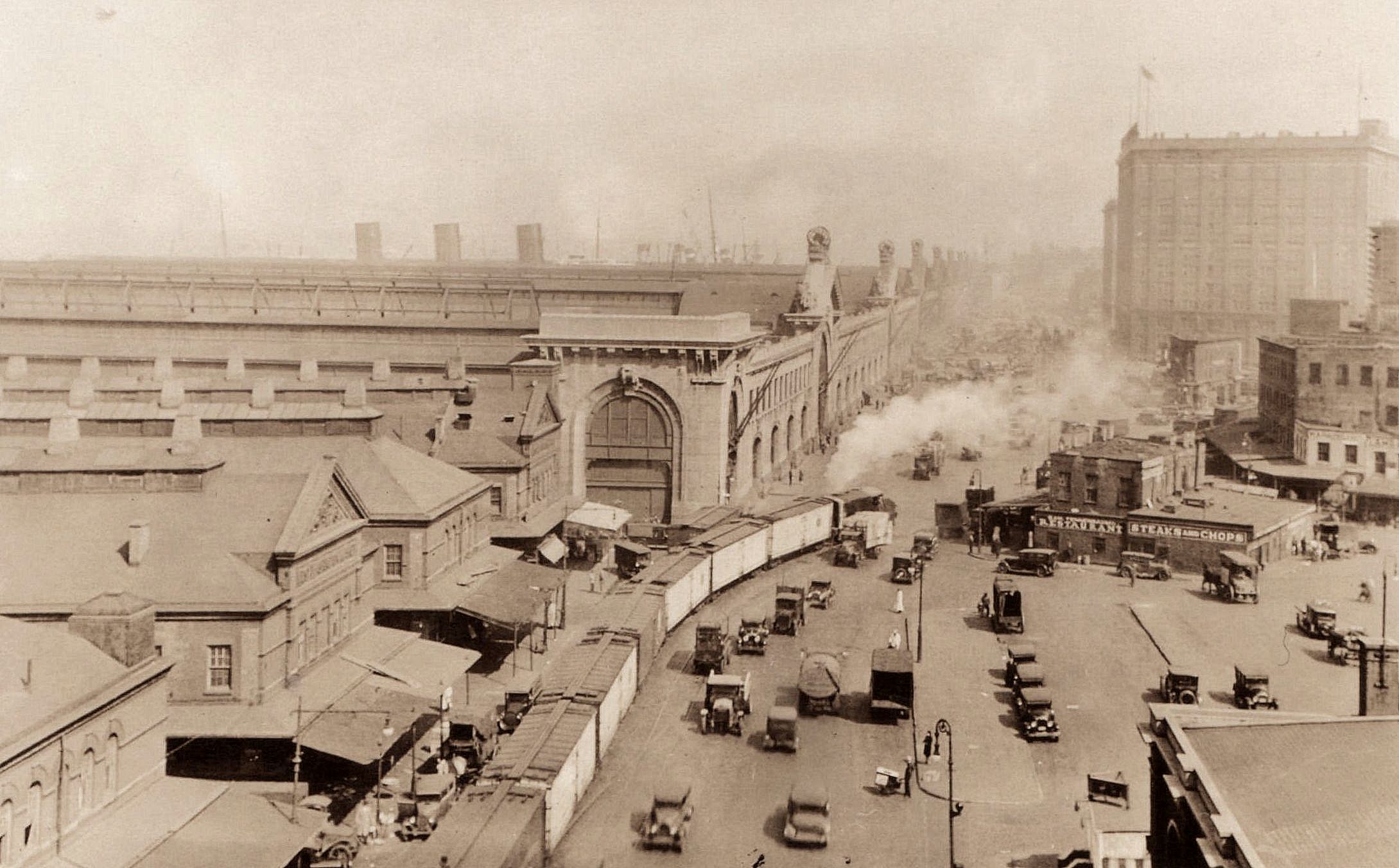

West Street (Twelfth Avenue) & Gansevoort Street (looking north) - April 31, 1929 northbound Shay type locomotive New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

||||||||||

| . . |

||||||||||

West Street (Twelfth Avenue) & Gansevoort Street (looking north) - April 31, 1929 Shay type locomotive shoving refrigerator cars in front of meat packers. Believed to have been taken from roof of Manhattan Refrigerating Co. New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 19 August 2025 |

||||||||||

| . . |

||||||||||

West Street (Twelfth Avenue) & Gansevoort Street (looking north) - April 31, 1929 Shay type locomotive running light. Believed to have been taken from roof of Manhattan Refrigerating Co. New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 15 August 2025 |

||||||||||

| . . |

||||||||||

West Street (Twelfth Avenue) & Gansevoort Street (looking north) - April 2, 1929 Shay type locomotive running light. Take from street level in front of restaurant in above photos. New York Public Library Digital Archives P. L. Sperr photo added 15 August 2025 |

||||||||||

| . . |

||||||||||

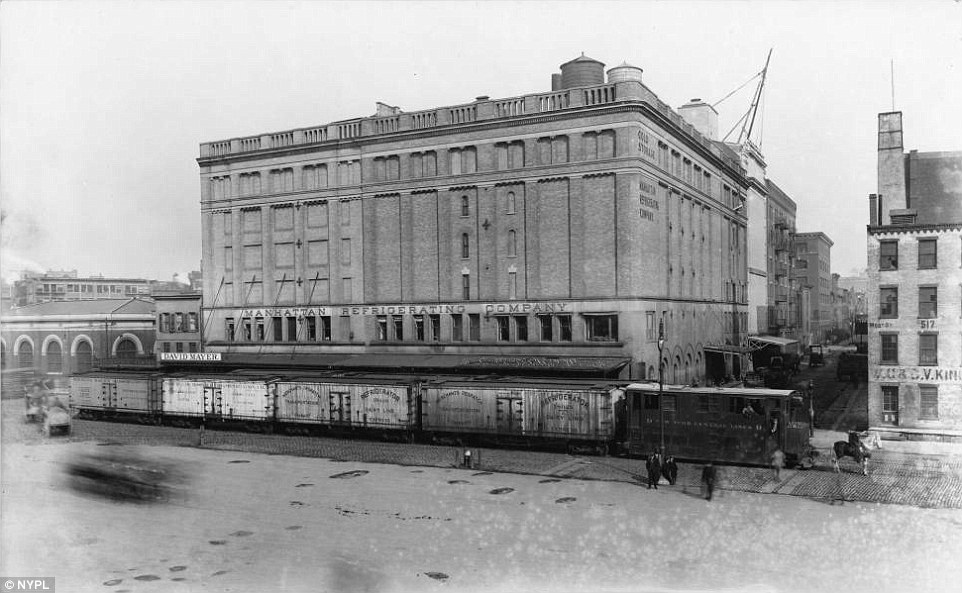

West Street (Twelfth Avenue) & Horatio Street - ca. 1915 Looking east at Manhattan Refrigerating Company / David Mayer. added 15 August 2025 . It is worth mentioning that the Meat Packing District's webpage on Manhattan Refrigeration is in error. It states:

"Artificial refrigeration and refrigerated trucking fueled the growth of the meatpacking business to an industrial and national scale. In the Meatpacking District, this was best exemplified by the Manhattan Refrigeration Company, which began operating in the neighborhood in 1898. The company built a massive complex that eventually included 9 buildings bounded by Horatio, Washington, West, and Gansevoort Streets. The complex was fueled by a central power station that delivered cooled air through underground refrigeration conduits to cold storage warehouses within an 18-block radius. These refrigerated buildings were not chilled by "cooled air" through street conduits, it was chilled salt water or brine that was pumped through the conduits. It was only inside of these buildings, that the chilled brine was passed through an evaporator where it chilled the air in that particular room or set of rooms. Basic thermodynamics clearly states chilled liquids will retain temperature better than chilled gases over distance. Chilled air (a gas) is not efficient for traveling distances as chilled liquids (salt water). A brine system uses a chilled liquid (salt water / brine) as a secondary refrigerant to transfer thermal energy from a target area (the freezer rooms) to a primary refrigeration system. The brine circulates in a closed loop to provide reliable cooling, especially for industrial applications that require temperatures below freezing. Thermodynamic principles: The brine cooling system operates on the principles of the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle, but with an intermediate step involving the brine.

Additionally, several City of New York documents state the Manhattan Refrigeration Co. (as well as others) paid a yearly fee for the placement of conduits to both draw salt water from the North (Hudson) River, was well as to pump chilled saltwater to the various buildings under the streets, and the New Washington Street Market. Many ice rinks use this system, where chilled brines is pumped through pipes cast in a concrete base, and where water is placed on top, to freeze. This may be trivial, but accuracy in history is paramount to a historian. |

||||||||||

| . . |

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| . . |

||||||||||

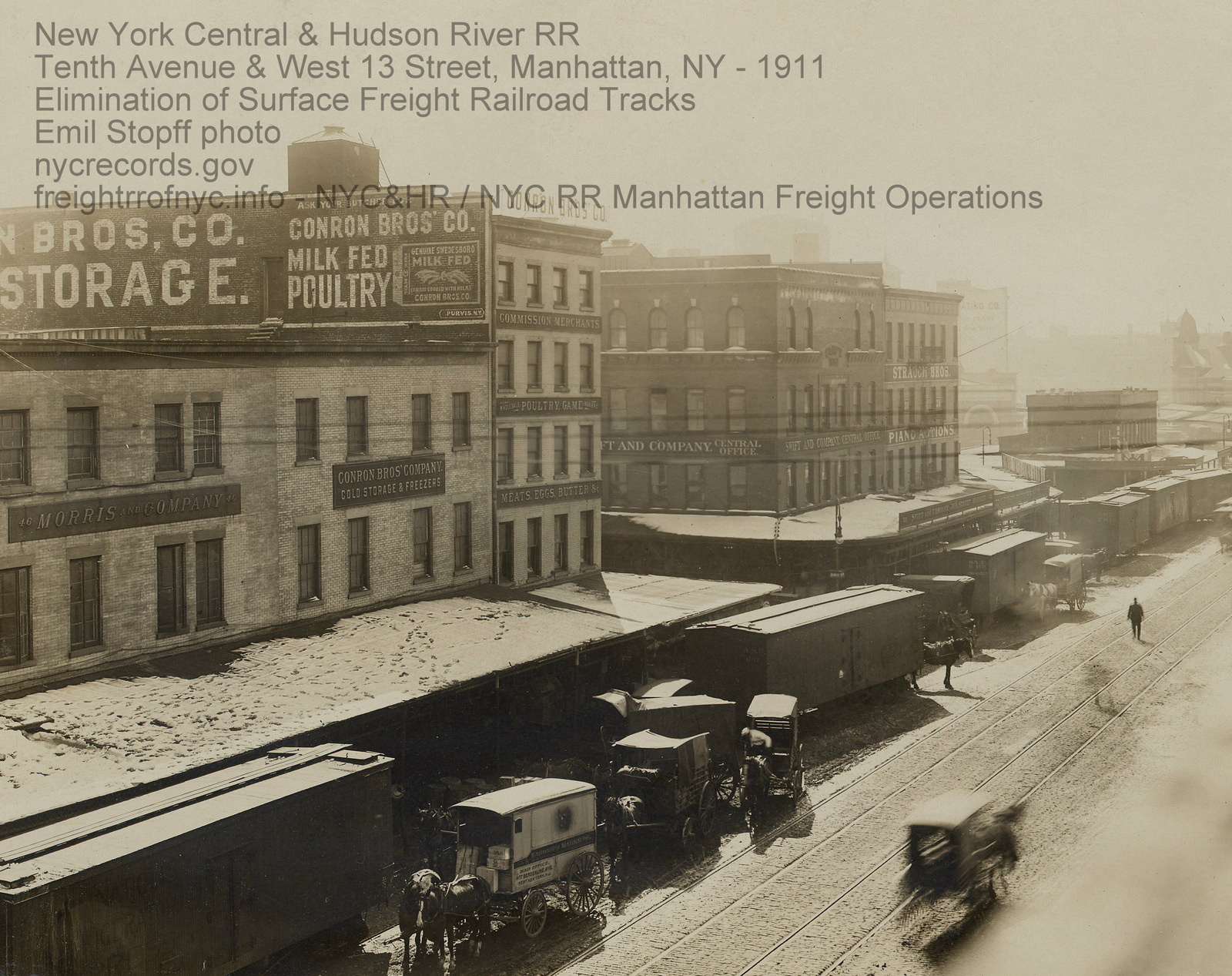

Tenth Avenue and West 14th Street - looking southeast - 1911 Morris & Company; Conron Bros. & Co; Commission Merchants; Swift & Co. 34 - 32 Tenth Avenue; Geo. Hotchkiss & Co 30-28 Tenth Avenue, Strauch Bros. Piano Actions added 15 August 2025 |

||||||||||

| . . |

||||||||||

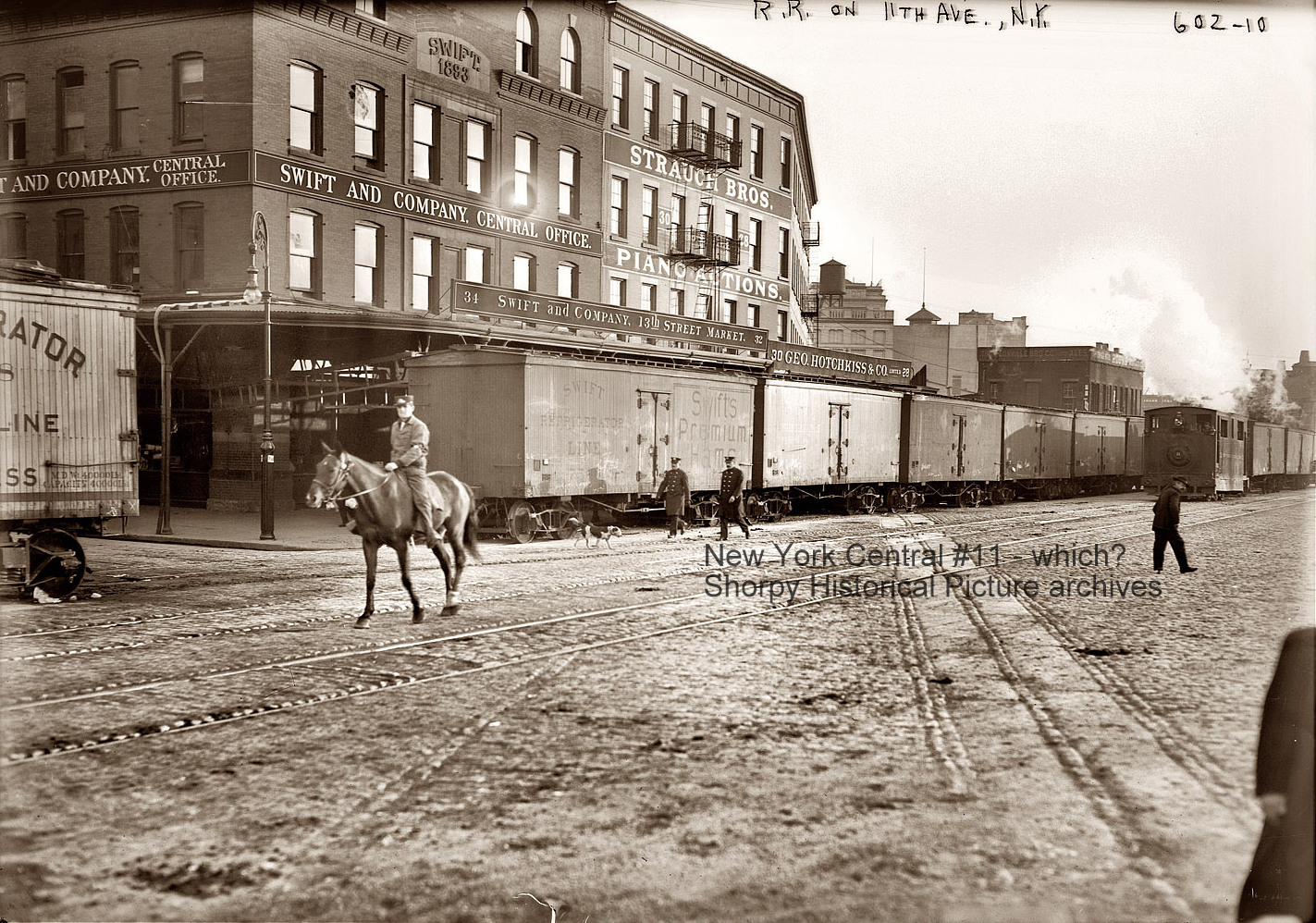

Tenth Avenue and West 13th Street - looking southeast Swift & Co. 34 - 32 Tenth Avenue; Geo. Hotchkiss & Co 30-28 Tenth Avenue, Strauch Bros. Piano Actions added 15 August 2025 |

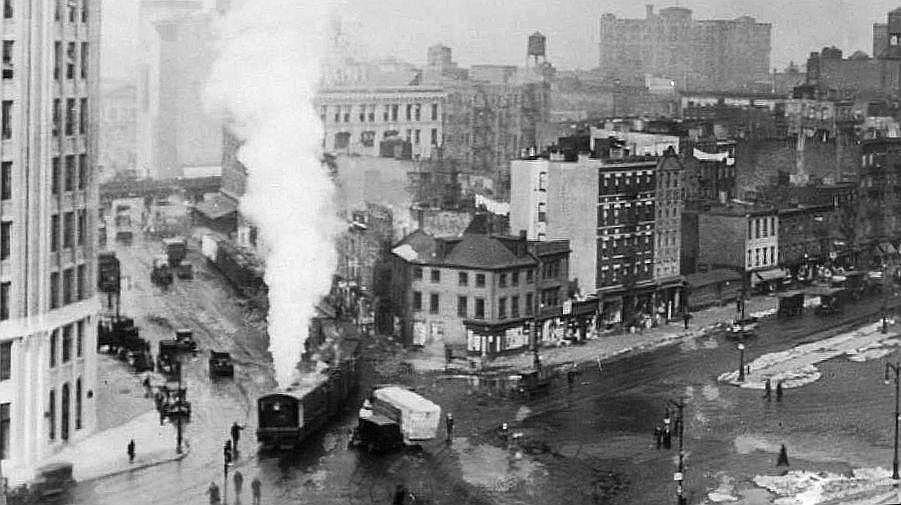

Locomotive on Canal Street turning right onto Hudson Street - unknown date Looking west. added 15 August 2025 |

| . . Old St. John's Park Terminal (first): 1868 - 1927 |

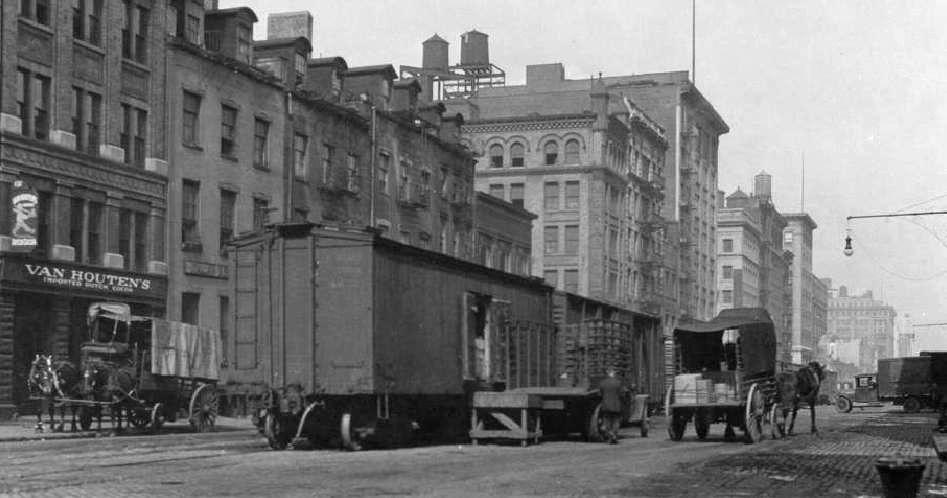

Hudson Street and Beach Street looking north - ca. 1920 St John's Park Terminal out of view right edge This is an interesting image for it shows portable ramps and platforms used for loading / unloading of boxcars on street trackage, thereby making them impromptu team tracks. added 15 August 2025 |

| . . |

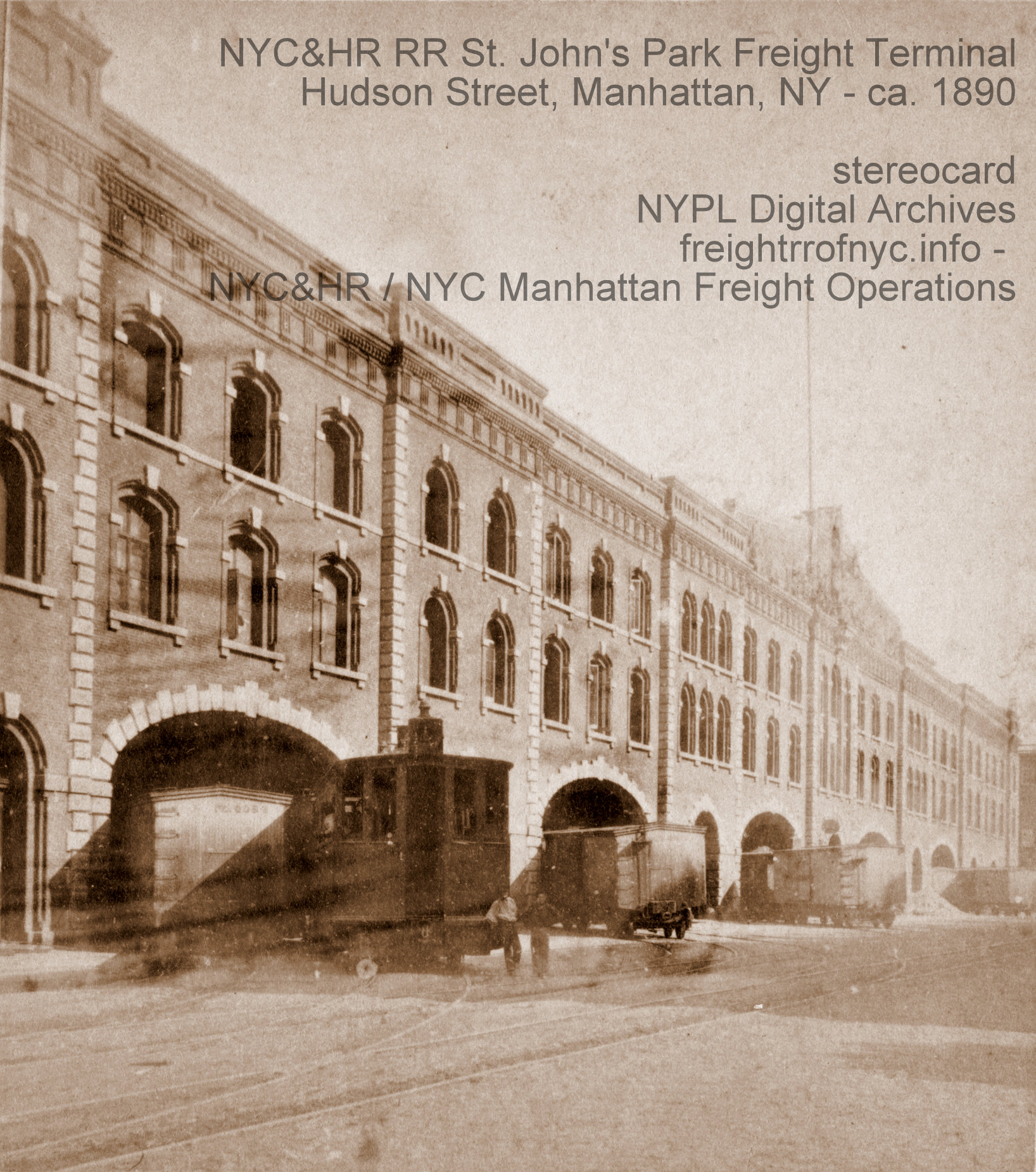

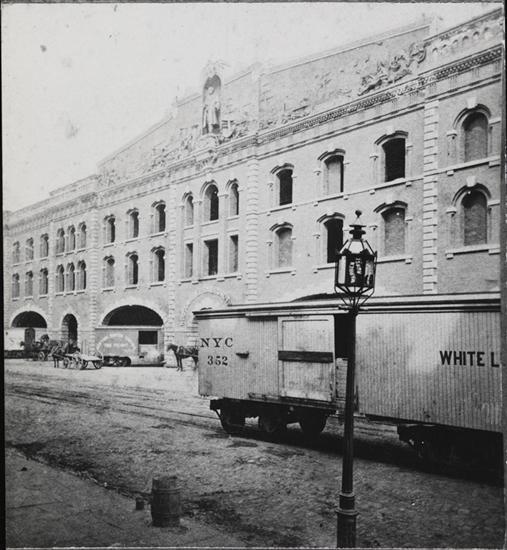

St.Johns Park Terminal - 1890 0-4-0T Dummy with crew posing on Hudson Street (looking southeast) Stereoview Card added 15 August 2025 |

| . . |

St.Johns Park Terminal - undated Hudson Street (looking northeast) added 15 August 2025 |

| . . |

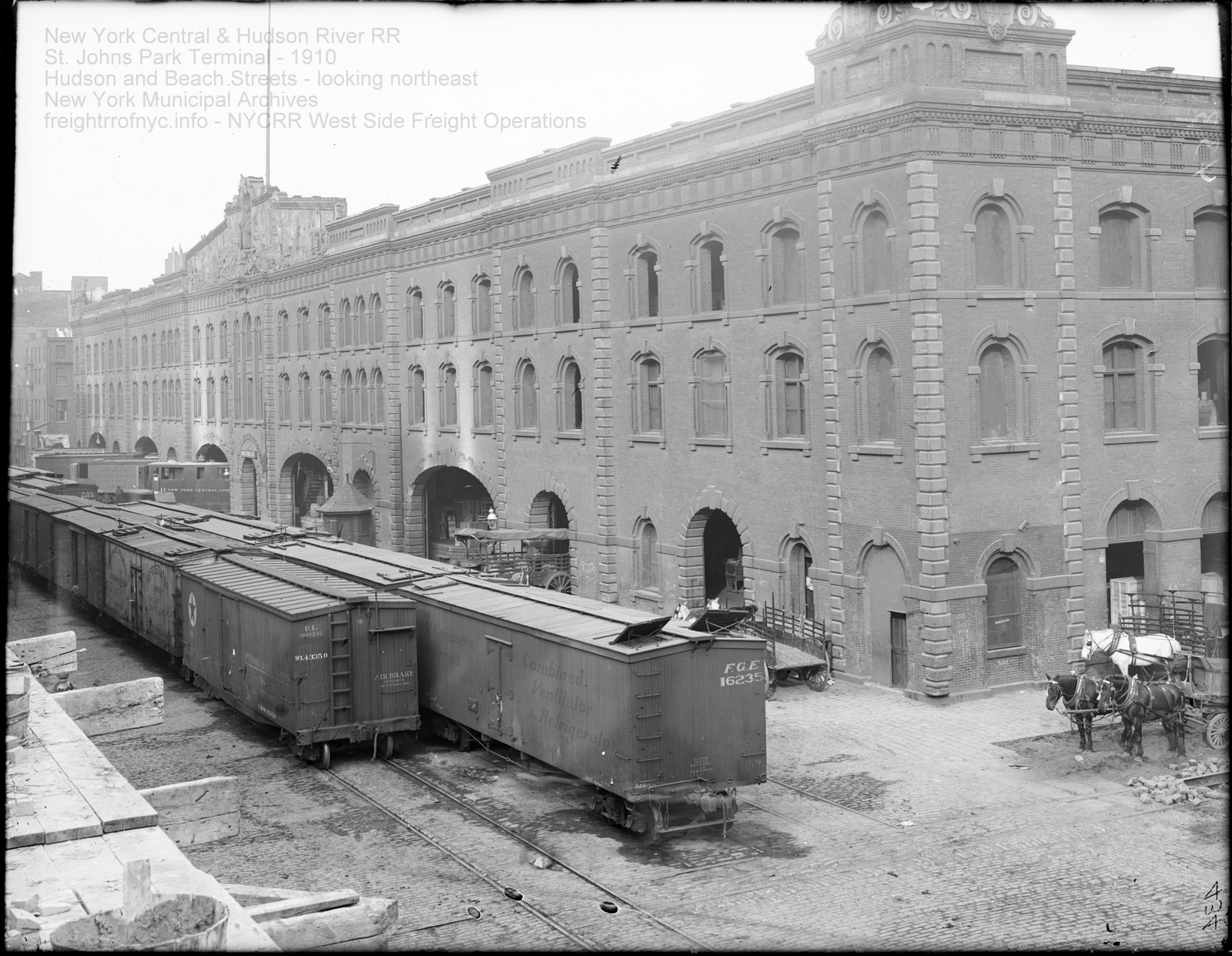

St.Johns Park Terminal - 1910 Hudson Street (looking northeast) New York Municipal Archives added 15 August 2025 |

| . . |

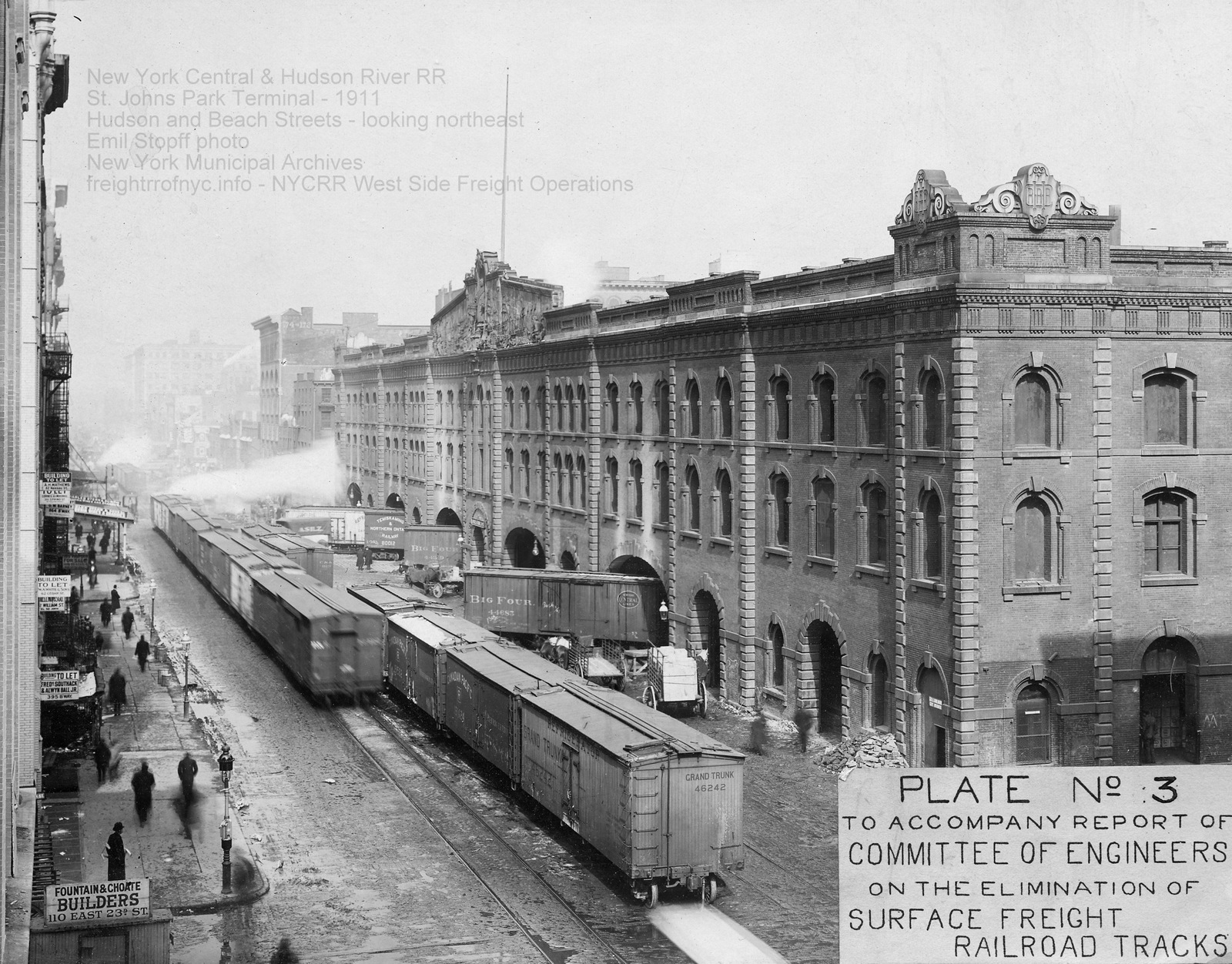

St.Johns Park Terminal - 1911 Hudson Street (looking northeast) Emil Stopff photo New York Municipal Archives added 15 August 2025 |

|

Little known (or remembered) to the general public